When my colleagues and I surveyed the state of gun violence at the start of 2021, we saw an accelerating crisis that had largely been pushed off the front page by the pandemic. Regular readers of our coverage knew that shootings had been ticking up since the early months of 2020 and showed no sign of relenting. We had documented how the pandemic both directly and indirectly affected violence in communities across the country, and we had tracked the unprecedented surge in gun sales that began in March 2020.

By the start of this year, we were determined to return to the deeper, often slower reporting that is central to our mission — work that few newsrooms have the time and resources to pursue. We picked up a few projects that had been delayed by the pandemic, including important work on the federal government’s failure to police gun dealers and loopholes in many states that prevent victims of domestic violence from getting their abusers’ guns taken away.

We deepened our groundbreaking investigation of the National Rifle Association’s financial dealings, while also dissecting the twists and turns in its bankruptcy trial. We expanded on-the-ground coverage of cities like Baltimore and Chicago, paying close attention to the root causes of gun violence. In June, we launched Up The Block, a resource guide for Philadelphians living with gun violence, and a new kind of community-focused initiative for The Trace. We also reported stories that show the human toll of shootings, the ramifications of discriminatory policing, and the harsh realties of rejoining society after incarceration.

I hope you’ll spend some time with this collection of 11 of our best stories, which together elucidate some of the critical contours of gun violence in America.

— Tali Woodward, Editor in Chief

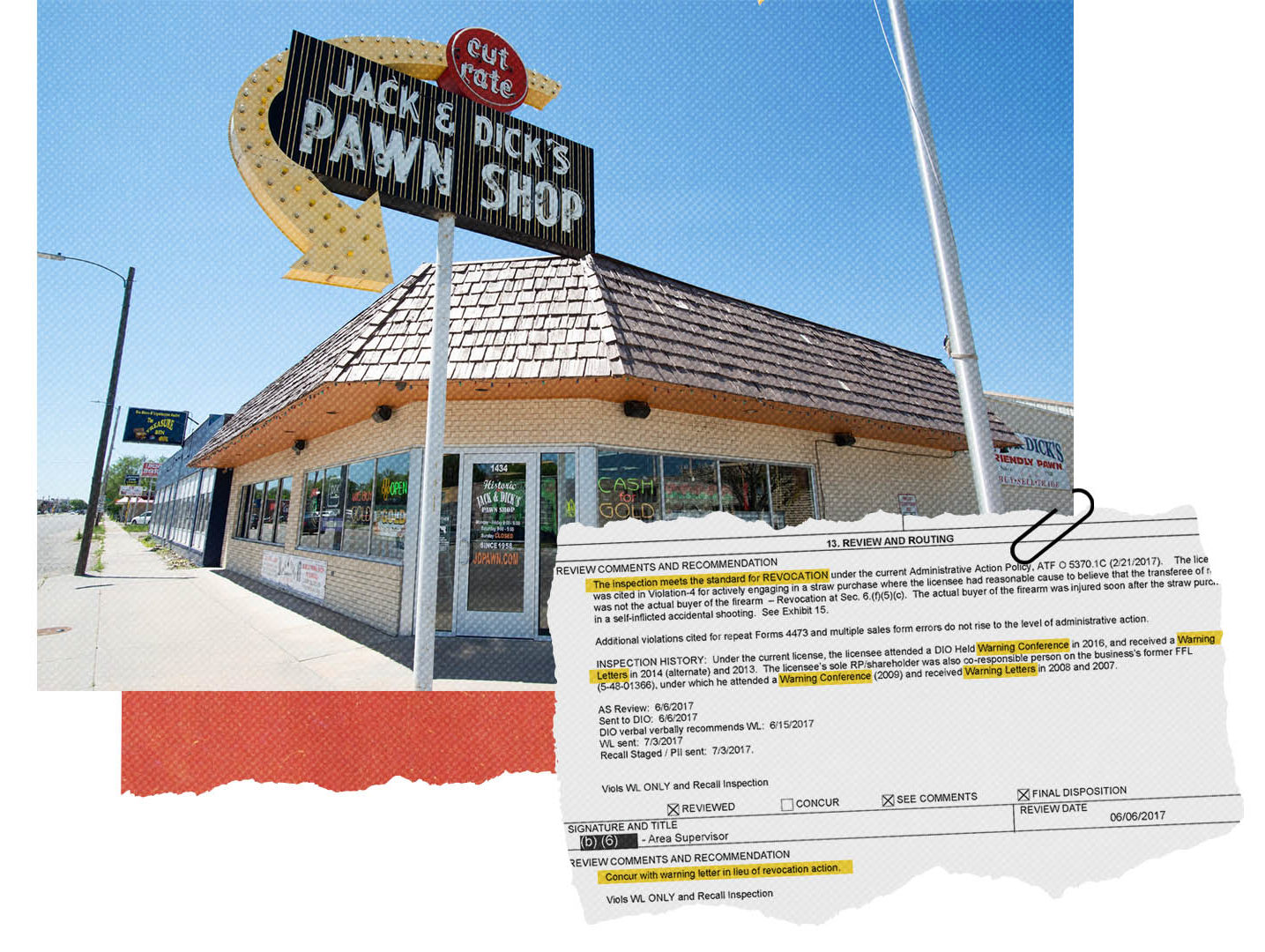

The ATF Catches Thousands of Lawbreaking Gun Dealers Every Year. It Shuts Down Very Few.

Brian Freskos, Daniel Nass, Alain Stephens, and Nick Penzenstadler, in partnership with USA TODAY

The Trace and USA TODAY wanted to know whether the federal agency responsible for inspecting the 80,000 federally licensed gun dealers in the U.S. was holding scofflaw dealers accountable. So we pored over documents detailing nearly 2,000 inspections conducted by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives between 2015 and 2017. The records — which were shared in a database that accompanied the final story — showed that the ATF was largely toothless and conciliatory, regularly going easy on wayward dealers and sometimes allowing guns to flow into the hands of criminals. Dealers sold weapons to convicted felons, transferred guns without conducting background checks, lied to investigators, and fudged records to mask their unlawful conduct. In many cases, the ATF issued warnings, sometimes repeatedly, but allowed stores to continue operating. Some dealers later became involved in trafficking schemes or sold guns used in crimes. In the months after The Trace and USA TODAY released their findings, the Biden administration directed the ATF to begin shuttering gun dealers that willfully committed certain violations, and congressional Democrats introduced a bill to give the agency more leeway and inspection resources.

When Protective Orders Don’t Protect

Ann Givens, in partnership with The 19th

When 21-year-old Michigan nursing student Rosemarie Reilly filled out the petition for a temporary protective order against her ex-boyfriend, she checked two boxes — one saying he had firearms, the other saying he had threatened to use them. A county judge signed the order but didn’t prohibit Jeremy Kelley from keeping his guns. In January, The Trace partnered with The 19th to tell the story of a tragedy that everyone saw coming, and no one prevented. Ann Givens’s article highlighted a big problem with temporary protective orders — which are typically in effect during the vulnerable days before a judge hears evidence in a domestic abuse case. According to one study of intimate partner homicides, 20 percent of people killed by their partner who had restraining orders against them were killed within two days of the order’s issuing. Thirty percent were killed within a month. Yet in 29 states and the District of Columbia, there is no process for taking guns away from the subjects of temporary protective orders. In another 13 states, including Michigan, a judge decides whether the subjects keep their weapons. After reviewing records in four states, Givens found that a person’s chances of getting a firearms restriction placed on their abuser are seldom tied to whether that person has threatened them with a gun. The potentially life-saving decision is more likely to depend on which county they live in and which judge hears their case.

Inside One Baltimore Group’s Effort to Stop Youth Violence Before It Starts

J. Brian Charles, in partnership with The Guardian

Baltimore was barreling toward a seventh consecutive year of record-setting violence when J. Brian Charles began to report on a program designed to work with the people closest to the conflicts. ROCA youth intervention workers criss-cross the city each day to counsel clients who are typically men between 16 and 24 years old. Many of these men are struggling to overcome exposure to trauma. The program uses cognitive behavioral therapy techniques to help them learn to regulate their responses to stress and conflict. The stakes are high, and ROCA team members maintain an often-frenetic pace trying to keep the city’s violence from catching up with the city’s young people. But the work is worth it. As one ROCA member told Charles, “If we can … teach them how to manage conflict by the age of 20, we’re setting the city up for success one young person at a time.”

Reporting on the National Rifle Association

Mike Spies, in partnership with The New Yorker

In 2019, The Trace exposed endemic corruption at the NRA, leading to multiple investigations and an ongoing legal battle with New York Attorney General Letitia James, who is seeking to dissolve the organization. Longtime NRA leader Wayne LaPierre has steadfastly denied wrongdoing and continues to raise funds as a populist crusader and authentic representative of gun culture. Through three stories published in partnership with The New Yorker, Mike Spies showed the truth behind LaPierre’s public persona. First, Spies obtained a video — deliberately buried for years — of LaPierre and his wife Susan shooting elephants in Botswana. The footage demonstrated that LaPierre was not proficient with firearms, as he failed to kill the creature at close range and required an associate to finish the job. A follow-up story detailed how the LaPierres had trophies from the Botswana hunt secretly shipped through an American taxidermist who transformed the elephants’ feet into stools for the couple’s home. In apparent violation of the nonprofit’s rules, an NRA contractor covered the costs. A final article, published this month, showed that LaPierre made dubious statements under oath during the NRA’s recent bankruptcy proceedings. LaPierre testified that he used a contractor’s yacht as a “security retreat” and the only place he could feel safe in the summer of 2013, six months after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. But Spies determined that the 2013 trip — the first of six annual Caribbean voyages — coincided with the Bahamian wedding of LaPierre’s niece Colleen Sterner.

Birmingham’s Young Mayor Promised to Radically Rethink Criminal Justice. Then Shootings Spiked.

Chip Brownlee, in partnership with Slate

Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin faced reelection in 2021 as the Alabama city was grappling with a shooting surge and struggling to balance police reform with gun violence prevention. In a race dominated by concerns over the violence, Woodfin — a young, Black progressive who’d spent nearly four years in office — found himself navigating a divide that seemed to mirror the national debate reignited by the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. To Woodfin’s right was a slate of challengers promising to be tougher on crime and more supportive of police. To his left were progressive activists and City Council candidates arguing that the mayor was too reliant on police and dismissive of non-law enforcement alternatives. As the election neared, Trace fellow (and Alabama native) Chip Brownlee traveled to Birmingham, where he found that the lines drawn in national debates over policing and how to best address gun violence are not always clear at the local level.

Black Mothers Are the Real Experts on Gun Violence

Arionne Nettles, in partnership with the New York Times Opinion, Flint Beat, MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, and The Oaklandside

Concerns about racist police violence are often framed as being in tension with Black people’s desire for safer communities. Over the course of eight months, Arionne Nettles, a Trace freelancer, asked Black mothers across the country about how gun violence had shaped their lives. The Trace co-published the interviews and accompanying portraits with The New York Times Opinion section as well as with nonprofit local news organizations led by women of color. The 15 women spoke candidly about their desires for systemic change — for more violence prevention program funds, greater resources for communities, and criminal justice reform legislation. The women also talked about their deep frustration with the injustices they’ve experienced — and the ways that they have been shut out of the public conversation. “We know that there’s nothing done if one of our own is killed in our community,” a mother from Chicago said. “And we’ve always been saying it’s wrong. And ‘when are we gonna get a break?’ And ‘when are they gonna stop killing us?’ But nobody was listening.”

To Escape a Legal Reckoning, the NRA Went Shopping for a Friendlier State

Will Van Sant, in partnership with The Daily Beast

When New York’s attorney general sued the NRA in August 2020, accusing its leadership of looting the nonprofit, CEO Wayne LaPierre declared: “We’re ready for the fight. Bring it on.” But behind the scenes attorneys for the gun group were seeking a means of escape. As Will Van Sant detailed in this story from March, NRA attorneys concluded in July 2020 that James had the group boxed-in, and they identified three legislative actions that an NRA-friendly state could take in order to create a safe haven. By the fall of 2020, the attorneys were mulling another gambit: bankruptcy. The NRA filed for Chapter 11 protection in Texas early this year. The move — which LaPierre and NRA outside counsel William A. Brewer III orchestrated without the knowledge or consent of the board — was a flop. LaPierre and others faced tough questioning, leading to new details being divulged in open court about the alleged misuse of funds. A judge eventually dismissed the bankruptcy, finding that the NRA had advanced bogus arguments in an attempt to gain an advantage over James, which is a misuse of bankruptcy law. Van Sant’s reporting laid bare the NRA’s bumbling effort to shield itself from accountability. In another story from November, Van Sant revealed that the NRA had paid a prominent gun rights scholar to produce favorable legal briefs in high-profile Second Amendment cases.

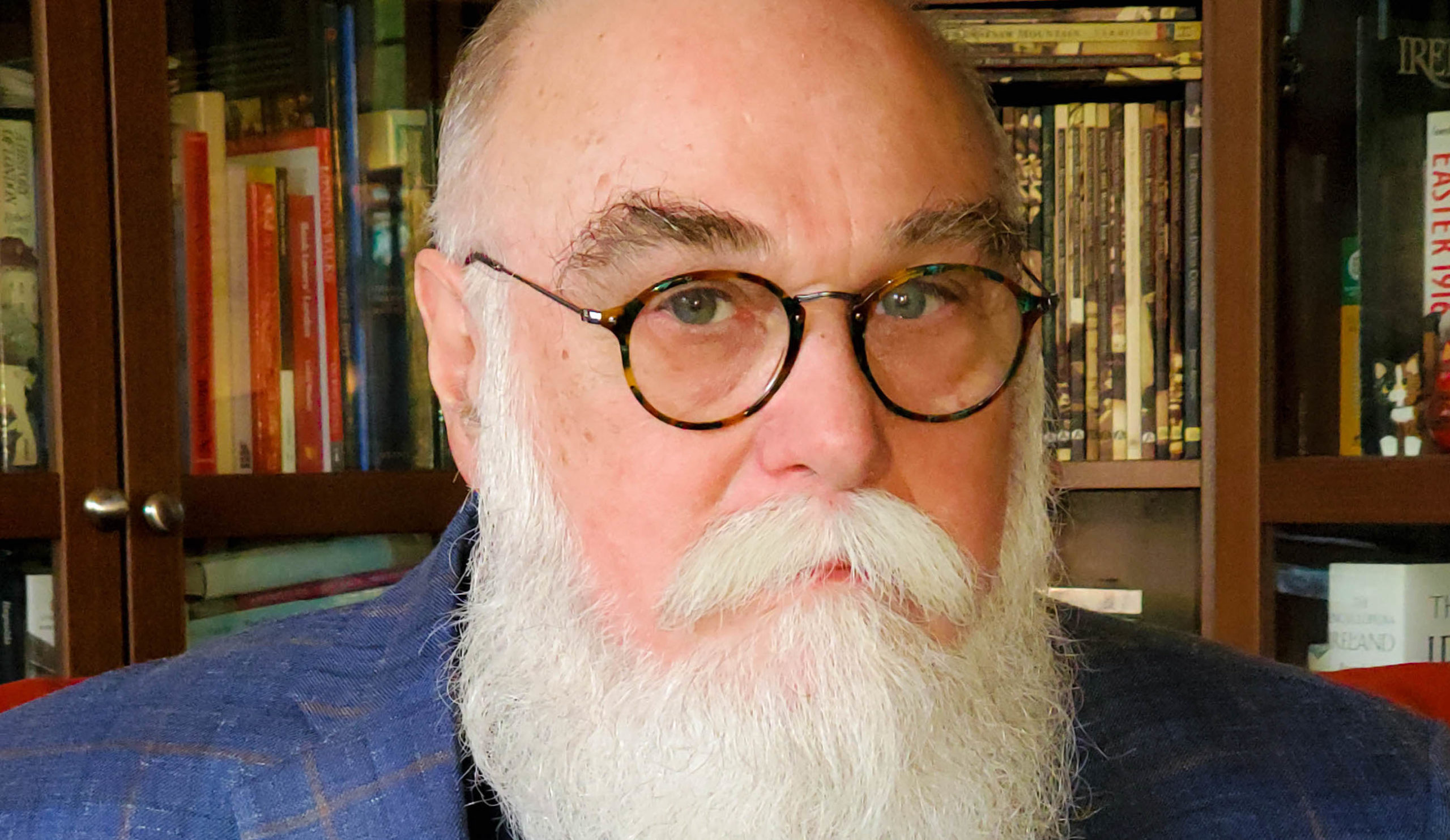

The Gun Data Expert Who’s Changing the Way the Media Defines Mass Shootings

Jennifer Mascia

Over the eight years that Gun Violence Archive founder Mark Bryant has been tracking gun violence nationwide, he’s tried to expand the media’s definition of “mass shooting.” Bryant’s group defines mass shootings as incidents in which four or more people were shot, regardless of whether any of them died. That differs from the FBI’s classification of mass murder, which counts only incidents in which four or more people were killed. Amid back-to-back high-profile gun rampages this spring in Atlanta, Indianapolis, and Boulder, Colorado, several mainstream media organizations began using Bryant’s broader definition — which encompasses high-casualty shootings in communities of color that are often overlooked. In a June Q&A, Bryant, a former computer systems analyst and lifelong gun owner, told Jennifer Mascia the surprising origins of the Gun Violence Archive and why he thinks the media’s emphasis on random acts of public gun violence is misplaced.

Illinois Has a Program to Compensate Victims of Violent Crimes. Few Applicants Receive Funds.

Lakeidra Chavis and Daniel Nass, in partnership with The Chicago Sun-Times, Block Club Chicago, and La Raza Chicago

Over the past decade, five in six of the more than 30,000 people shot in Chicago survived. Survivors are often on their own to cope with the aftershocks — the medical bills, the PTSD, the potential unemployment. Lakeidra Chavis and Daniel Nass examined a program that’s supposed to help crime victims with costs not covered by insurance. Their analysis of nearly 15,000 state victim compensation claims processed between 2015 and 2020 revealed that fewer than four in ten applicants received reimbursement money, and that just one application was filed for every 50 violent crimes. Survivors like Zay Manning often wound up on the other side of the paperwork with nothing to show for it. While reporting this story, Chavis found out that Manning’s application hadn’t been rejected like he initially thought; the young man just needed to submit more paperwork. And there’s reason for broader hope: New legislation will increase the maximum award, and advocates are holding officials accountable for helping the program live up to its promise.

Up the Block

Sabrina Iglesias

Philadelphia has endured more than 500 homicides in 2021, the deadliest year in the city’s history. Residents of the neighborhoods most affected by such violence don’t always get a voice in conversations about how to stop it, but if you ask them, you’ll find they have important things to say about how the city can better support and protect them. Sabrina Iglesias, The Trace’s Philly-based community engagement editor, spent a year developing Up the Block, a resource guide that addresses what she heard in conversations with Philadelphians who live with gun violence every day. She worked with local freelancers Emily Neil and Afea Tucker to compile information on organizations that provide services to trauma survivors, crime victims, people trying to keep their children safe, and more. Up the Block launched in June as a searchable guide to these organizations, available in both English and Spanish. We’ve appreciated the supportive response from the local Philly community — including our media partners Billy Penn, Resolve Philly, The Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting, Philadelphia Free Press, and Kensington Voice — and our peers in the national media. In 2022, we plan to expand the project with information on how to get involved in local government, and to develop new partnerships with journalists and organizations throughout the city.

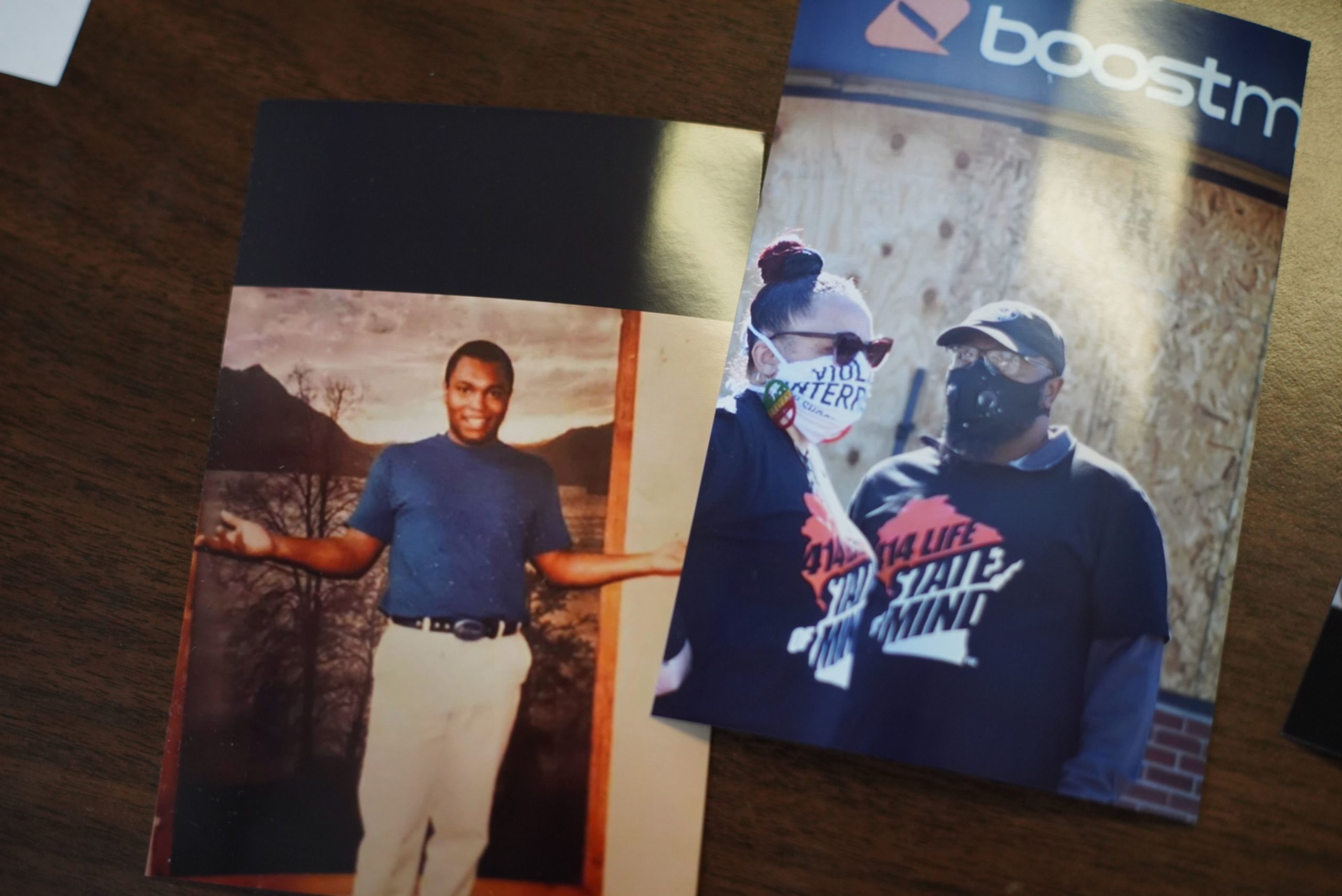

To Shed a Cage

Champe Barton, in partnership with The Guardian

Milwaukee violence interrupter Hamid Abd-Al-Jabbar and his friend and client David Thompson spent half of their lives in Wisconsin prisons, the consequence of decisions they made with guns as children. Champe Barton’s joint profile charts the men’s life stories against the hardening of Wisconsin’s prison sentencing regime, as state officials in the 1990s all but abandoned the concept of rehabilitation for people convicted of crimes. The system thrust Jabbar and Thompson, and many men like them, into a cycle of release and rearrest that has been difficult to escape — despite their best attempts to do good. Over dozens of conversations with the friends and their families, Barton learned about how the pair needed miracles to stay free, and even then, nothing was guaranteed.