Shortly after the May 26 shooting at a San Jose, California, light rail yard, which left nine people dead, national media outlets seized on a pair of sobering statistics: The rampage was the 232nd mass shooting in 2021, and the 17th mass shooting in the U.S. in less than a week.

The source of those figures is the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive (GVA), an increasingly sought-after resource for gun violence statistics. GVA defines mass shootings as incidents in which bullets hit four or more people, regardless of whether any of them die. That differs from the FBI’s definition of mass murder, which only counts incidents that lead to four or more people being killed, by guns or any other means. News outlets have long relied on the FBI’s definition in reporting on the prevalence of mass shootings. But amid back-to-back high-profile gun rampages this spring in Atlanta, Boulder, Colorado, and Indianapolis, several mainstream media organizations — including The New York Times, USA Today, NPR, and CNN — are using GVA’s broader definition.

While federal and state tallies of gun injuries and deaths can take more than a year to be released, GVA tracks shootings in close to real-time. Its staff of two dozen researchers culls news articles and police reports to provide up-to-date figures on mass shootings, defensive gun use, suicides, and other categories of gun violence. GVA makes its data available free of charge on its website.

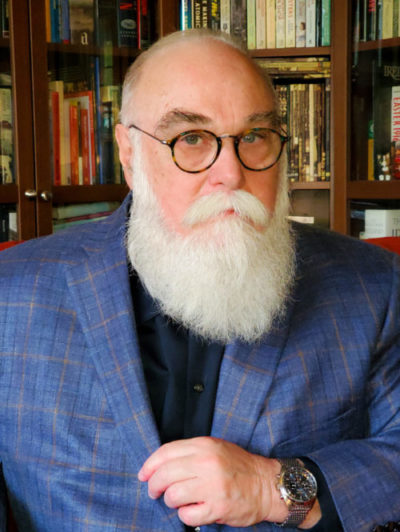

GVA is an outgrowth of a project launched by Slate in the aftermath of the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre to provide an accurate accounting of how many people were shot each day. Slate’s efforts prompted Mark Bryant, 66, a retired computer systems analyst and lifelong gun owner in Lexington, Kentucky, to begin compiling his own figures. He found incidents Slate had missed and emailed the editor. By the end of 2013, Bryant had taken over the project and turned it into GVA.

In a recent interview, Bryant revealed the surprising origins of the project — he got the money to hire his first employee by selling guns — and shared his thoughts on why the media is embracing a more expansive definition of mass casualty rampages. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

So you were a retired computer systems analyst, you emailed Slate and said, “You’re missing people in your tally.” What made you want to be the person who filled in those gaps?

I was hospitalized from late 2011 through early 2012 for a blood clot. While I was in the Intensive Care Unit, I got to thinking and decided that I had one good job left in me. I considered a couple of options. One of them was gun violence. I’m a gun owner who understands gun regulations, and I knew there had to be solutions that people weren’t paying attention to. Then Sandy Hook occurred. I was sure that would be the game-changer that finally brought about reforms. But nothing happened, and that caused me to get really pissed.

How did you get GVA off the ground?

It’s a funny start. I don’t think most people in gun violence prevention have a clue as to how guns are used as a currency. I had done some database work for a guy, and I handed him a bill, but he didn’t want to pay me. But he said, “Pick you three guns.” He had like 800 guns. I looked at it and picked three Colt Pythons, which I knew had a very, very high value. Well, he had not put any caveats on it, so he begrudgingly gave me those three. Later on down the pike, I sold them for $2,500 each to a 70-year-old guy that collects guns. So that was $7,500 that let me hire my first person at Gun Violence Archive. We now get funding from Michael Klein, who co-founded the Sunlight Foundation. We also have secondary funding from a couple of other folks.

What’s it like during a typical shift at GVA?

We have a master list of 7,500 sites that we go to daily. It’s everything from The New York Times to Hey Jackass. Some of them have paywalls, so we have subscriptions to entirely too many media. We also hit police sources: police Twitter, police Facebook, police websites. Everyone has a region. I’ll use one of my staffers as an example. She’s got Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, so she may hit 200 sites a day. A lot of them you spend three minutes on, because you know which ones are going to have gun violence as a headline and which ones are going to require you to do a deeper search on their site.

Every once in a while we make errors, but we usually get them corrected. Sometimes by us. Sometimes by reporters. Sometimes by the family. A woman called me two days ago saying we had reported the victim was an adult male when it was really a female child. The woman was the child’s mother. I’ve had some mothers and aunts and sisters who will send me death certificates, pictures of death certificates, of police reports, everything if I’ve got something wrong or they want something on the permanent record.

Why did GVA settle on a definition of mass shootings that was different from the FBI’s definition of mass murder?

We were trying to come up with something that was reasonable and made sense. So we talked to the FBI who basically said, “We’re not in the business of doing definitions.” But they did have a definition for mass killings, which was four killed. So we took that as the basis. Then we noticed that when news outlets describe a shooting, it’s “shooting,” “double shooting,” and “triple shooting.” You seldom see “quadruple” or “quintuple.” For four victims, you start saying “mass” or “multiple.” Some people only will look at the mass murders. And then other people will parse out gang shootings or workplace shootings, or they’ll parse out all sorts of categories to make the numbers smaller. And I can’t tell if that’s to help their political point of view, or if it’s to make their job easier.

When did you notice an uptick in news outlets citing GVA’s mass shooting tally?

I honestly don’t remember which one started it, but we keep a scrapbook of major times — not all times — just major times that it’ll be, “according to the Gun Violence Archive.” After this latest spat of mass shootings, damn near everyone adopted our definition. The two headline-grabbing numbers — mass shootings so far this year and mass shootings in the last 30 days — required accepting that definition. It is about time that the media began to standardize this phrase. We were talking about CNN. They literally cut and pasted our definition for mass shooting into their definition of mass shooting. The humorous part is, a long time ago in my previous life, I was one of the four engineers, architects that designed CNN’s digital newsroom. So in at least part of their business I know them deeper than they know themselves.

But I always like to point out that mass shootings account for about 5 percent of our work. The media puts much more effort into the 5 percent than the 95 percent. And that to me is a problem. Why does the media have enough resources that I can tell you that in a 1963 game between the New York Yankees and the Boston Red Sox, it was a cloudy day, this many people had hits, this many people had strikeouts, but these cities cannot do a box score for gun violence? Think about that. People need awareness. And if everybody just did a daily box score, think about how that would raise awareness.

Do you think the broader definition was adopted because they are, as you described, headline-grabbing numbers?

As we got over 150 mass shootings in mid-April, that was a significant number, and to get to that number you had to use our broader definition, which is four or more people killed or injured. Using a narrower definition blows off all the people who are injured.

There was the Aurora, Colorado, movie theater mass shooting in 2012 that killed 12 people. That got massive coverage, which it should have. But three days earlier there was a shooting at the Copper Top bar in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, that injured at least 17 people. That’s 17 people who can’t work, 17 people who can’t necessarily do everything they could the day before. In Hollywood movies, characters like John McClane get shot, laugh it off and go on, but that’s not how life works, and I think folks are starting to realize that. If you use the narrow, parsed definitions, you remove violence in minority communities.

Many news organizations find GVA to be a valuable resource. What would happen if you stopped?

Well, that’s a good question. What if something happens to our primary funders? What happens if I find myself under a coal truck? We have transition plans in place. So if I go away, things continue. I think in another five years CDC might have a project together that will collect much of the data. Will it still be real time? I doubt it. So if journalists are looking for real-time data, we’re it right now. Nobody does what we do. Nobody. I plan on us being around, and we’re going to continue to get better at what we do.

There are times that I would really like for it to be over. The longest vacation I’ve taken in the last eight years was only about four days. I’m desperate to go to a beach. But I also think about when I was sitting in the hospital and decided I had one good job left in me. This is it. This is exactly what I needed.