The pastors huddled together as if preparing for battle, asking God for guidance. Moments later, they found the mayor in the lobby of City Hall. They had come to ask him for something. But as the faith leaders formed a semicircle around Mayor Randall Woodfin, two of Birmingham, Alabama’s most powerful institutions collided.

The pastors wanted Woodfin to allocate American Rescue Plan money for violence prevention programs.

The mayor wanted their help fundraising for Crime Stoppers, an effort that pays tipsters for information that can help solve crimes. It’s a means to end what Woodfin has called a “no-snitch” culture and solve shootings that have injured or killed numerous children.

The pastors knew they had leverage. They represented dozens of predominantly Black churches, with prodigious congregations made up of some of the city’s most consistent voters. “You see these folks right here?” one of the pastors leading the group, the Reverend T.L. Lewis, told Woodfin, as he gestured to the other pastors. “We got armies.”

Neither side was willing to budge.

Birmingham, like many other cities, has seen calls for police reform and skyrocketing gun violence over the past year. Many of its staunchest progressive activists have effectively abandoned the young mayor over what they call his pro-police attitudes. Meanwhile, he faces a reelection challenge on Aug. 24 from candidates who have positioned themselves as more supportive of police.

“People want to box me in and make me choose between reform and accountability measures, and policing and keeping the city safe,” Woodfin said in a June interview. “No, I reject your ultimatum. I can walk and chew gum at the same time. We can do both.”

Many young progressives assume that given the long history of racist policing, Black people want a smaller police force. But in Birmingham, and many cities, that’s not the case. Woodfin, since early in his tenure, has said that most of his constituents, particularly older residents, want more patrols. Though older Black people may view police less favorably than their white counterparts and desire reforms, many still see police as a main way to combat violence. Even some activists admit as much. National surveys provide some support for Woodfin’s argument, showing that younger people across racial groups are more likely to support defunding the police. While Black voters are more likely to distrust police, they didn’t prefer decreasing police patrols to increasing them.

Public safety and crime have become a central focus of Birmingham’s 2021 municipal election, the first since protests swept the nation after the murder of George Floyd. At the same time, homicides have increased some 5 percent in the city in 2021, after 2020 marked its deadliest year since 1995. So far in 2021, the city has recorded 65 criminal homicides, putting it on pace to surpass last year’s record. Most victims are young, Black men.

In the wake of recent violence — along with rising activism and the opportunity for political change — people who consider Birmingham home are springing into action. The moment has prompted an outpouring of new ideas and proposals, uniting and sometimes dividing residents on addressing a complex problem. Activists have launched City Council campaigns. Woodfin is rolling out new initiatives. And grassroots organizers and the pastors, with the support of unexpected allies — including some in law enforcement — have embarked on an unprecedented push to fund alternative public safety strategies, because they believe that relying primarily on law enforcement simply doesn’t work.

“This is where the revolution starts“

2017 was a violent year in Birmingham, with the city recording more homicides than it had seen in two decades. Much like 2021, the near-record violence shaped a contentious election. Woodfin, then a 36-year-old attorney and city School Board president, emerged as the main challenger.

Woodfin quickly found himself on the national radar as Democrats looked toward down-ballot races in Donald Trump’s first year in office. Like many people across Birmingham, Woodfin had personal ties to the gun violence epidemic: He lost his brother to a shooting and, just weeks before Election Day, his nephew.

He was a young progressive in the heart of Alabama, invigorating supporters and activists in search of their next champion. Our Revolution, an outgrowth of Senator Bernie Sanders’ unsuccessful 2016 presidential bid, and Collective PAC, a political action committee that supports Black candidates, endorsed Woodfin.

“In these urban areas of the Southeast ― this is where the revolution starts,” Woodfin said in 2017. He proposed reforms that would be the most radical in Birmingham’s history: promising to create a free college program, institute a $15 minimum wage, and lobby for “Medicare for All,” Sanders’ health care proposal.

He cited his experience as both a prosecutor and defense attorney as evidence that he would be able to ensure public safety, fight for criminal justice reform and racial justice, and hold police accountable. Woodfin said he wanted to address the root causes of crime — disinvestment in low-income communities and persistent, generational poverty.

Since 1960, the Magic City’s population has declined nearly 41 percent, to about 200,000 today. While economic downturn played a role, another significant driver was white flight during desegregation.

In recent years, new tech companies and developers invested heavily in downtown Birmingham. Those gains didn’t boost predominantly Black communities, like Pratt City, where dozens of homes stand dilapidated or collapsed, schools and businesses have closed, and the population has declined.

And those Black communities most harmed by the legacies of segregation, redlining, and deindustrialization are most affected by gun violence today. As the city’s manufacturing and steel industries declined, many people who once worked in industry shifted into low-paying service sector jobs — or moved away entirely. Today, 26 percent of people in Birmingham live in poverty.

By the time Woodfin was running for office, the city’s response to violence relied heavily on law enforcement. A few years earlier, in 2015, then-Mayor William Bell had billed the new Birmingham Violence Reduction Initiative (BVRI) as a community-based approach. The partnership between police, the Mayor’s Office, prosecutors, and community leaders connected men deemed most likely to engage in, and be victims of violence, with counselors and social services.

But the program blurred the line between social supports and police enforcement. Counselors would show up at participants’ homes with help and an ultimatum: Stop the violence, or you’re going to jail. This approach came to a head in 2017, when, as part of a BVRI enforcement effort, police cars raided Central Pratt. With its SWAT vehicles and public restraint of young Black men, the raid’s intensity thrust Eric Hall — whose 69-year-old mother’s home was blocked by police vehicles — further into activism.

“That was the first time I’d ever seen an actual armored vehicle in Birmingham,” said Hall, who is now an outspoken leader of the local Black Lives Matter chapter and Our Revolution. After the raid, the initiative lost steam, its decline cemented by a negative review from John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

As he ran for mayor, Woodfin piled on. His approach to handling violence, he said, would be a “poverty reduction initiative.” At the same time, he said he planned to grow the Police Department somewhat.

But Woodfin’s focus on inequality and his positioning himself as a disruptor of “politics as usual” fired up activists like Hall — and their expectations for a different kind of mayor, one who would address constant reminders of neighborhood decline. Local progressive groups, with their text messages and phone banks, made up a significant portion of the grassroots movement that catapulted Woodfin into a runoff and, later, to victory in what was expected to be a close race.

“Unorthodox ways”

As he prepared to take office, Woodfin offered a prediction about what was to come: The choices he would soon have to make to address crime made him “anxious,” he said, “because I know that there are things I’m going to have to do in unorthodox ways.”

To disrupt violence, Woodfin thought, Birmingham would need to target prevention, reentry, and enforcement. In 2018, he established the Mayor’s Office of Peace and Policy to work on the first two pieces. The office engages nonprofits and the city’s Tuhska Lusa Initiative to prevent recidivism among Black men through social support and group therapy.

The next year, he launched the Birmingham Promise Initiative, which gave students paid internships and covered the cost of their higher education.

But the honeymoon ended when he and the U.S. attorney announced a task force targeting violent crime. The effort combined local and federal law enforcement agencies, the local housing authority, and prosecutors to target and apprehend key offenders who officials believed were responsible for most violent crime.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

Then–Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who previously represented Alabama as a U.S. senator, selected Birmingham as one of 12 initial cities to participate in a new National Public Safety Partnership, shifting federal resources into local law enforcement and some local gun possession cases into federal court — despite research showing that longer prison sentences and elevated incarceration rates associated with shifting gun charges to federal court do little to deter violent crime.

“Birmingham voters believed that any work initiated by Mayor Woodfin to deter crime and violence would center root-cause analysis and comprehensive grassroots and community-based solutions,” several Black Lives Matter leaders wrote in an open letter at the time. “This is why it was a hard pill to swallow.”

When asked about this critique, Woodfin pointed to a generational divide between older residents — the most consistent voters — and younger people. “When I talk to the mommas and the big mommas in the neighborhoods, they want more police,” he said in 2018. “People my age and younger say more policing is wrong. As mayor, I’m in the middle.”

“Reimagining public safety” after George Floyd

Birmingham’s Black residents’ history of facing police brutality left a mark on federal and local policy and politics. Segregationist Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor’s vicious and nationally televised attack on young protesters in 1963 paved the way for the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Later that decade, one of the city’s greatest icons, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth — who organized the Birmingham Campaign with Martin Luther King Jr. — focused on integrating the police and ending police brutality. And the city elected its first Black mayor, Richard Arrington Jr., in 1979 in the aftermath of the police shooting of Bonita Carter, a young Black woman, in large part because of Arrington’s work to address racist police abuse. Now, Black leaders oversee Birmingham’s police force.

The protests of 2020 prompted Woodfin to launch another task force to “reimagine” public safety. The result was a 100-plus-page report of recommendations: creating a branch of public safety that would dispatch medics and mental health workers to nonviolent 911 calls; making policing more transparent; developing robust community-based prevention programs; and reallocating some law enforcement funding to programs that take a public health approach.

Woodfin didn’t accept every recommendation, but since the report’s release, the city has announced a pilot to send social workers, along with police, to some domestic violence calls. In April, Woodfin created the city’s first Civilian Review Board to investigate complaints of police misconduct. He pardoned 15,000 people for past misdemeanor marijuana convictions to make it easier for them to get jobs. Over three years, his Birmingham Promise grew from a small pilot to a program expected to send more than 600 students to college this fall. And in July, Woodfin banned the use of no-knock search warrants.

As protesters and activists called for further alternatives to traditional policing, Woodfin rejected cuts to the police budget; instead, in 2020, he proposed an increase. The $11 million boost didn’t cover new officer positions. Much of it was an accounting shift and funds for more equipment, and the budget proposed eliminating 48 vacant officer slots. At the same time, the budget cut other workers’ salaries, instituted furloughs, slashed funding for public transport, and gutted social services like local libraries. Amid the furor of the budget debate, Woodfin and the city ignored funding requests from violence intervention groups including the Birmingham Peacemakers, one of the groups leading, along with the pastors, the effort to invest in community-based gun violence prevention under the umbrella of Fund Peace.

With disagreement over Woodfin’s task force, the relationship between Woodfin and the city’s activists was already tenuous, and this fight was the final straw. In January, the Birmingham chapter of Our Revolution publicly rescinded its endorsement. A few months later, after police shot and killed a 28-year-old Black man named Desmon Montez Ray Jr., the local Black Lives Matter chapter would call for Woodfin’s resignation, along with that of the police chief.

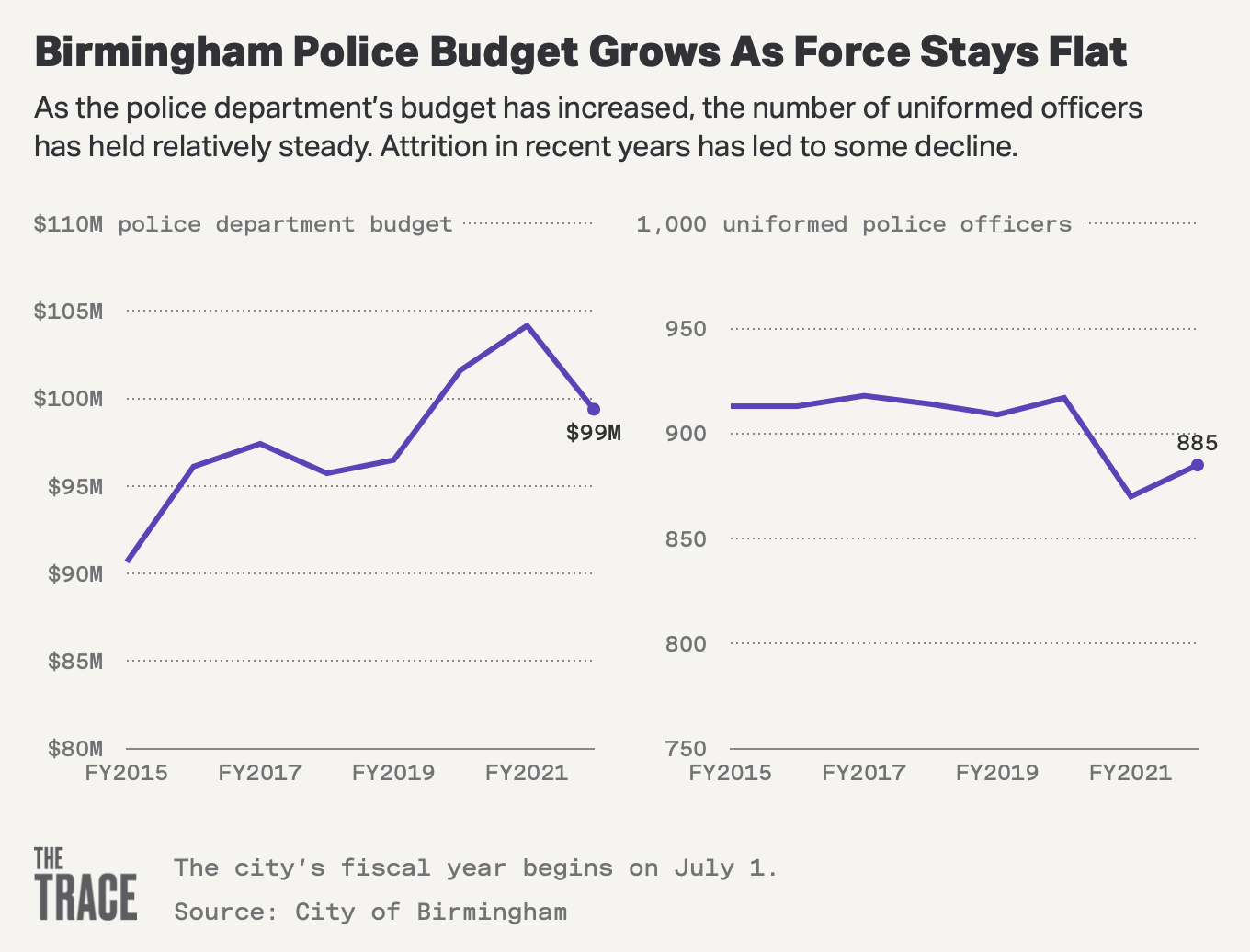

If anything, Woodfin has been less bullish on bolstering the police than his platform might have suggested in 2017. When he ran, he promised to grow the police department from approximately 914 to 1,000—in addition to addressing poverty. In that time, though, the number of officers has decreased to 885, according to the latest city budget.

“I wish people would check the record,” Woodfin said.

Woodfin said he has delivered on his promise, and that the city has focused on modernizing the department and its crime-fighting strategies while also trying to make policing more just. The city is scheduled to complete a real-time crime center this summer, with new technologies like predictive policing to speed up response times, he said.

“When I hear people say, ‘Black folks ain’t doing nothing,’ I know it’s wrong”

At a Black-owned book and coffee shop in Birmingham’s Five Points West community, Celida Soto met several women to discuss their community. In Birmingham, activists like Soto and Hall, the Black Lives Matter leader, believe that Woodfin — or whoever is elected mayor — needs more checks. So they’re running for the City Council in their respective districts.

In March 2020, Soto’s son wanted to attend a Lil Baby concert at the Birmingham CrossPlex, a new arena meant to bring economic development to western neighborhoods. She had concerns about safety. “I don’t know,” she remembers telling her son. “There’s a lot of violence here.”

But she wanted him to have something to look forward to, so she took him. Shortly after Lil Baby began performing, she heard gunfire ring out. Soto and her son took off running, along with other concertgoers, before she fell to the ground. “You gotta get up!” her son told her.

“I’m supposed to be protecting him, but I got trampled,” she recalled. She wasn’t physically injured, but the shooting left them both with trauma.

Over the course of an hour, a half-dozen women trickled in and out of the shop, Homecoming Coffee, which serves as a community gathering place. Books by Doris Barren, Sanovia Muhammad, and other local authors lined the shelves. Over coffee, the women lamented the violence — and its causes.

Soto blames the pervasive violence on underresourced schools, poverty, and several other factors — along with the shared trauma of going through it all. “We don’t have to live like this,” she said. She also blames disinvestment and poor city services. She said her neighborhood had relatively few trash bins, a disparity that leaves it dirtier than wealthier, whiter neighborhoods. She regularly picks up trash but has to walk nearly a mile to toss her garbage bag. “People feel like the city doesn’t care about them.”

If elected to the City Council, Soto said, she would push for participatory budgeting, support new violence interruption programs, and overhaul the city’s responses to emergency calls — more broadly than Woodfin did.

The women at the shop each had personal connections to gun violence. Yvonne Thomas, who volunteers with other Black women to help people with substance addiction and recently launched a transitional home for women, lost her son to a shooting. Vernessa Barnes has watched her 16-year-old grandson organize Solutions, a youth conflict and gun violence prevention group.

“When I hear people say, ‘Black folks ain’t doing nothing,’ I know it’s wrong. Black folks are doing so much,” Thomas said. “We are taking care of ourselves.”

Less than 48 hours after Soto met the women at Homecoming Coffee, Lykeria Briana Taylor, 21, was shot in her car and killed, just a few hundred feet away.

It’s all about the money

On June 8, less than a week after the group of pastors campaigning for Fund Peace met Woodfin at City Hall, the mayor had different pastors behind him—and a bigger audience ahead. At the press conference, he announced a partnership between the city, the pastors, and Crime Stoppers to combat gun violence against children. A rash of shootings killed or injured six children under 10 in 2021, including a deputy sheriff’s 11-month-old daughter; police had solved just one.

Woodfin blamed some residents for not coming forward with information on the shootings. “We have a lot of cowards out here in our community, and the thing about a coward is they’ll keep shooting,” Woodfin said. “This community is at an inflection point.”

“I don’t care what your code is,” Woodfin said in an interview. “Children shouldn’t be shot, and if they are, we as adults should be pushing those shooting it up to the front of the line.”

Woodfin stressed the need to balance law enforcement with prevention and reentry work, he said, “because you can’t arrest your way out of this.”

The pastors from the Fund Peace campaign weren’t at Woodfin’s press conference because Woodfin, in the moment, turned down their proposal for spending Birmingham’s cut of American Rescue Plan money — $140 million over two years — on violence prevention. They rejected the mayor’s request for help raising money for Crime Stoppers, saying the pandemic had made fundraising for their own congregations hard enough.

While the American Rescue Plan doesn’t have a specific designation in it for anti-violence work, the Biden administration has made clear that federal recovery money can pay for evidence-based community violence intervention programs. So far, Woodfin hasn’t committed to that.

Woodfin’s administration put out a call for ideas on how to spend the money, receiving more than 150 submissions, which he’s now reviewing with the City Council. Woodfin’s team will make a proposal to the City Council, which has final say on how to spend it. Woodfin’s proposal does include “community-based public safety initiatives,” but when asked by the City Council, he wouldn’t clarify what that meant.

Everyone, from pastors to police to residents, is tired of the violence in Birmingham: the harm it causes, the way it tarnishes the city’s reputation, the business it deters. “I am sick and tired of people talking negative about our city,” City Councilor Crystal Smitherman said at a July summit in support of the Fund Peace campaign. “It’s time for the communities to step up and take charge of our neighborhoods.”

To the Reverend Gregory Clarke, 63, of New Hope Baptist Church in Birmingham’s West End neighborhood, police are not the answer. “I’m not saying they don’t do their job — they do their job of responding to crime,” said Clarke, the founder of Birmingham Peacemakers and a leader of the local Fund Peace campaign. “The police had their budget increased. But the effect on crime didn’t match. Matter of fact, it went up.”

The intensity of Birmingham’s exasperation at the constant violence is blurring the lines between would-be foes in the effort to bring peace by investing in alternatives to policing.

Woodfin’s main challengers in this election are former Mayor William Bell, businessman Chris Woods, and Jefferson County Commissioner Lashunda Scales. All three of them, to varying degrees, believe that police should play a role in addressing Birmingham’s homicides. Bell wants to bring back an updated version of BVRI, Scales wants to increase the presence of police and law enforcement agencies, and Woods has said Woodfin’s grip on public safety is “weakening.”

Though not everyone agrees on reducing the number of police officers, the pastors and organizers of Birmingham’s Fund Peace campaign have made allies with Scales and Bell.

Even local law enforcement leaders, including the county’s first Black sheriff and district attorney, say, like Woodfin, that Birmingham can’t “arrest its way out of” gun violence. They’ve joined the call for using the relief funds for community-based gun violence prevention efforts.

And on the left, after years of seeking city funding, the Birmingham Peacemakers and the pastors’ Fund Peace campaign found a supporter on the City Council in Smitherman. She recently submitted a request for the Fund Peace campaign to receive $400,000 in American Rescue Plan money. Smitherman lost her uncle and, earlier this year, her cousin to gun violence. She said she believes Woodfin and the police have done what they can to address violence but a true solution will require a broader effort.

The county’s Health Department has also publicly backed the Peacemakers, leaving Woodfin on his own again, as one of a few local leaders who hasn’t.

Because of these alliances, community-based violence prevention programs, under the umbrella of the Fund Peace campaign, may be on the cusp of getting city funding for the first time. The City Council is expected to take up the issue later this month. Meanwhile, voters will decide Woodfin’s fate — and the shape of the rest of city leadership — at the ballot box.