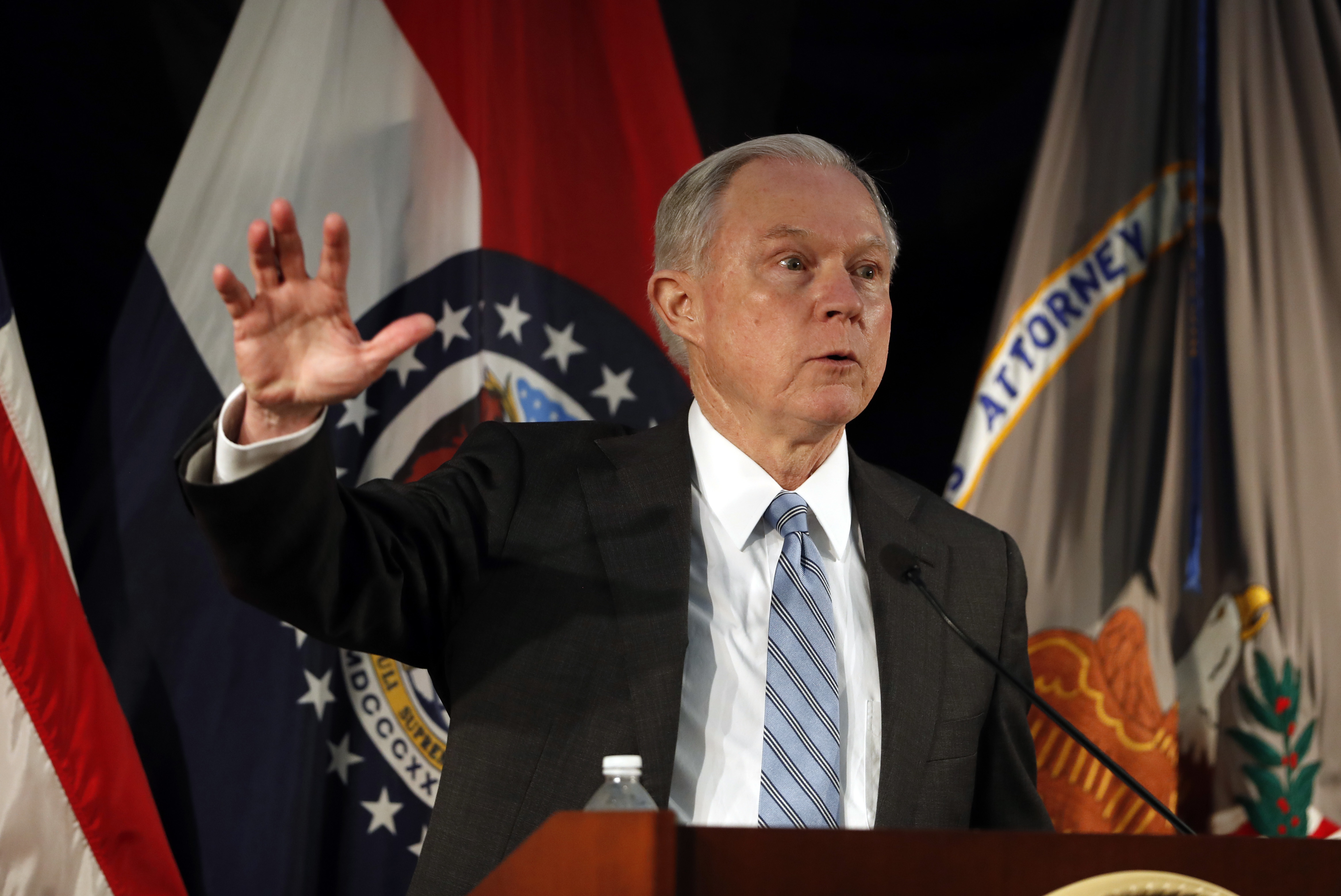

Newly minted Attorney General Jeff Sessions was in St. Louis, the latest stop on his tour to promote his muscular solution to what he called the “dangerous new trend” of the rising national violent crime rate. Addressing a crowd of more than 200 federal and local law enforcement officials at the city’s towering federal courthouse in late March, he vowed to “use every lawful tool we have to get the most dangerous offenders off America’s streets.”

The Trump Justice Department has pushed a variety of strategies for reducing violent crime. But the tool that Sessions prefers, the one he calls the “excellent model,” is to steer more gun-crime cases to federal court, where offenders face an average of six years in prison, compared with the lighter punishments that can result from state convictions — in Missouri, for instance, gun offenders charged under state laws generally get probation. Sessions has instructed his U.S. attorneys to step up their gun-case loads, and they are heeding his mandate: In the second quarter of this year, federal firearms prosecutions jumped 23 percent over the same period in 2016.

In his St. Louis speech, Sessions praised the city’s U.S. attorney’s office for its aggressive pursuit of gun-law violators, framing its work as the first half of a tidy formula.

“The more of them we put in jail,” he said, “the fewer murders we will have.”

But Sessions is dramatically overselling the effectiveness of his prosecution-heavy prescription, those who study gun violence say. Researchers, in fact, long ago concluded that the long prison sentences and elevated incarceration rates that result from increasing federal prosecutions have scant influence on violent crime rates. And St. Louis is a signal example of why Sessions’s strategy does not work as he promises.

No other city has already tried harder and longer to do exactly what Sessions is pushing for nationwide. Since the 1990s, the St. Louis-based Eastern District of Missouri has remained in the top 10 federal court districts for per capita gun prosecution rates, according to data from Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). In more recent years, the St. Louis office has only increased its intake of gun cases, leading the nation in 2016.

At the same time, St. Louis’s rates of homicide and serious crimes of all types are the worst in the country, and have been stuck at or near the top of that dubious list for at least 20 years. The city recorded 188 homicides in each of the past two years—a two-decade high. During the first six months of 2017, murders kept pace with those brutal levels. Nonfatal shootings were up an alarming 22 percent.

If St. Louis shows why Sessions’s approach to gun violence is destined to fail, what is a more effective role for federal authorities to play in reducing violent crime? Public safety scholars say that it starts with recognizing that no two cities’ crime problems are exactly alike. The next step is to create a menu of interventions tailored to meet local needs—and support them with reliable funding.

“At the end of the day, you need a balanced, evidence-informed strategy that is not just about a program or two,” says Thomas Abt of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, who formerly served as New York State’s head of public safety and was chief of staff in the grant-funding arm of the Obama Justice Department. “It’s about how multiple programs interact to produce a cumulative effect.” That argues in favor of federal officials as researchers, advisers and funders—not just enforcers. “We should leverage the soft, supportive power of the federal government a bit more, and the hard power a bit less,” Abt says.

A few miles from where Sessions delivered his March speech, a soldier turned social worker named James Clark runs an anti-violence program that would be grateful for whatever federal support it can get. His organization, Better Family Life, practices a form of intervention that multiple studies have shown can work to reduce bloodshed if properly implemented.

For the better part of two years, Clark has tried in vain to raise the money to hire dozens more outreach workers to counsel young men against resolving disputes with lethal force. If the federal government were serious about reducing homicides and assaults, he argues, it would deploy personnel to spend time understanding the dynamics of violent crime at the ground level, rather than impose solutions “from the perspective of a conference room.”

Clark doesn’t foresee that happening. Under the Trump administration, Justice Department and congressional budget cutters have done their best to whack funding for effective violence-reduction programs in their respective spending proposals, and there’s no sign that people on the ground will change their minds.

“To take a deeper dive, you have to go places that most people won’t feel comfortable going,” Clark says. “You have to talk to people that most people don’t feel comfortable talking to.”

In late 2012, gun violence in St. Louis had local officials feeling overwhelmed. Shootings had spiked over the summer, capped by the murder of a former St. Louis University volleyball player visiting campus for an alumni game. To try to quell the carnage, city officials turned to federal authorities for a special show of force.

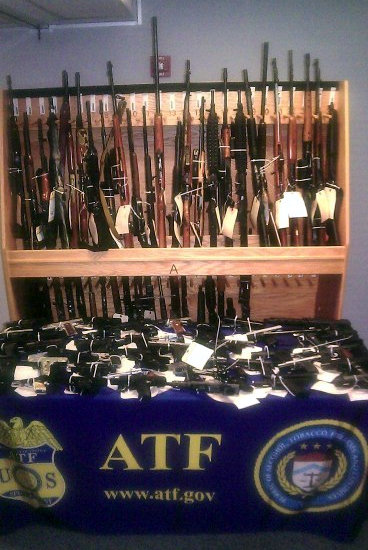

Out of their call for help came a pair of sting operations by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. The bureau launched the push in secret in January 2013. Under the code name Operation Hustle City, 80 federal agents swooped into the city to take illegal guns and their carriers off the streets. In one sting, undercover ATF agents opened a tattoo parlor called Ink Pimp, where agents posing as outlaw bikers put out the word that they would pay cash for black-market guns. The phony deals netted charges against 25 people and the seizure of 129 firearms and small amounts of drugs. Another team recruited people willing to stage a violent robbery of a fictitious drug stash house. That led to 40 more arrests.

At the operation’s grand-finale news conference in July 2013, the weapons haul was laid out on a table for the obligatory photo op. Then-Mayor Francis Slay took his turn at the microphone to proclaim mission accomplished. “It will reduce gun violence,” Slay said. “It will make us safer.”

That’s not how others saw things. While all two-dozen Ink Pimp arrests resulted in convictions and prison terms of one to 12 years, a highly critical report by the Justice Department’s own inspector general concluded last fall that Operation Hustle City generated mostly insignificant prosecutions and no valuable informants or intelligence. The IG’s office called the operation and others like it around the country poorly managed, thanks to ATF’s “lack of specialized training, poor planning, and lack of oversight.” The fake Ink Pimp shop had cost $260,000 to run, but ATF agents were so heedless that they failed to notice an after-school program just one block away from where the ersatz tattoo parlor was luring gun-toting felons.

As a violence-reduction tool, Operation Hustle City failed miserably. Citywide, shootings have since surged. Ink Pimp’s neighborhood, in particular, ranked among the nation’s worst for concentrated violence in 2015.

“The clients I had who were swept up in those things were people who I would say in several cases would not have been involved in what they did but for the possibility of a safe sale to these yahoos in this phony store, or being persuaded to engage in this phony robbery of a stash house,” says Michael Dwyer, an assistant federal public defender who represented people nabbed in the stings. “Because these yahoos were promising them easy money.”

“I don’t know of a single credible evaluation that shows us that sting operations bring down rates of violent crime and help keep them down,” says Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri at St. Louis.

That reality has not dampened federal law enforcement’s long-running enthusiasm for short-term operations like Hustle City—nor for efforts to funnel more gun cases into federal courts. In St. Louis, local authorities have been happy to cooperate.

Lt. Col. Jerry Leyshock, a 37-year veteran of the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department, says the department likes having an alternative to state courts, which local police complain can be too lenient. “Sometimes we do a little shopping,” he says, to see “where we can get the best bang for our buck.” TRAC data show where its shopping frequently leads: In St. Louis, city police and prosecutors refer gun defendants for federal charges at a rate seven times the national average.

In fiscal year 2015, the Eastern District of Missouri took on 228 gun cases, good for 78 per 1 million people, the third-highest rate among the nation’s 94 federal court districts. In 2016, prosecutions rose by another third to 301, or 103 per 1 million residents. The rate put the district in a tie for first with the district based in Mobile, Alabama—not coincidentally, the district where Jeff Sessions served as U.S. attorney in the 1990s and adopted a forerunner to the hard-nosed policy he is now using as AG.

St. Louis is a lot like other cities, however, in one important respect: It does little to target the sources of the guns. Busts of scofflaw stores are rare. In the Eastern District of Missouri, federal prosecutors tend not to pursue charges against straw purchasers—people who buy firearms on behalf of someone whose criminal background would make them ineligible—because they regard the cases referred to them by the ATF as too trivial, says Richard Callahan, the former U.S. attorney in Missouri’s Eastern District. “There was certainly never any source of supply of guns to the bad guys that was ever brought to our attention.” He adds, “I don’t think they existed” in eastern Missouri, where he and others blame state gun deregulation and a rash of gun thefts for keeping the criminal market well stocked.

Rather than tackle the supply side, federal gun prosecutions tend to focus on unlawful possessors or users. Proponents see the cases as having a multiplier effect: For every individual offender sent away to prison, many more will be dissuaded from illegally carrying a firearm. The more cases you prosecute and the longer their sentences, the theory goes, the fewer illegal gun users at large and the safer the streets.

It’s a model that came into vogue in the crack cocaine and gang crime waves of the 1980s and found its clearest expression in an initiative called Project Exile. Launched in 1997, Project Exile shifted gun crimes to federal court to take advantage of its mandatory minimum sentences. It was revived in last year’s presidential campaign via a Trump position paper that called for the restoration and expansion of the “tremendous” program and offered a preview of the promise Sessions has been making since his confirmation hearings: “When we do, crime will go down and our cities and communities will be safer places to live.”

While one 2005 report (authored by Rosenfeld, as it happened) found Exile worked in its pilot city of Richmond, Virginia, other research has generally panned it as ineffective at reducing violence. By teasing out the possible multiple causes of drops in homicides, one study concluded that “almost all of the observed decrease probably would have occurred even in the absence of the program.”

The problem with leaning on lengthy federal sentences to scare potential violators straight is that it uses the wrong lever, according to the Justice Department’s own research arm, the National Institute of Justice. As the institute notes in a 2016 summary, it’s “the certainty of being caught”—not the severity of the possible sentence—that can have a strong deterrent effect on potential criminals.

But as local police departments well know, illegal gun charges are notoriously hard to make stick. In state courts in New York City, for instance, the rate has hovered around 50 percent. Cases fall apart for a number of reasons: The heightened danger officers perceive when a Glock is discovered poking out from under a waistband during an already tense stop can lead to imprecise evidence handling. In court, defense attorneys succeed in raising doubts about the true ownership of street guns that may be shared by a group of friends. Thanks to a Missouri law that allows guns in cars without a permit, 4 out of 10 gun arrests in St. Louis, according to a recent study, never resulted in charges at all.

There’s one more reason why it doesn’t make sense to expect federal firearms prosecutions to reduce gun violence: The strategy misunderstands the nature of most shootings.

Selling his approach, Sessions has linked gun crime to gangs and drug trafficking, arguing, “If you want to collect a drug debt, you can’t, and don’t, file a lawsuit in court. You collect it by the barrel of a gun.” But city-level law enforcement data suggest that in homicides where a primary motive can be determined, drugs drive fewer killings than more prosaic arguments, fights and personal disputes. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study of homicide data from five cities further found that even among gang killings specifically, “homicides commonly were not preceded by drug trade and use or with other crimes in progress.”

A federally funded report on violent crime in St. Louis released this March reached a similar conclusion about the city’s gun violence, determining that personal conflicts among young black men make up a vastly disproportionate share of shootings.

In his police work, Jerry Leyshock has observed the same phenomenon. “You’d be surprised at how many murders that I looked at last year, when we finally just got to the meat of it, it had nothing to do with gangs, dope, or anything,” he says. Instead, “it was over the most senseless things you’ve ever heard of.”

There should be no mystery about what Washington could do to more productively help bring down shootings in St. Louis. It’s all spelled out in the same March white paper that traced most of the city’s violence not to drug syndicate shootouts, but interpersonal beefs. The report was produced by the federal Office of Justice Programs’ Diagnostic Center, with Rosenfeld among the contributing scholars, and included a list of violence-reduction strategies that consistently prove most effective.

One of those, called “hot spots policing,” uses data-driven hit lists to search for contraband firearms or known shooters in an area where gun violence is concentrating. In another, “focused deterrence” (often referred to as the Ceasefire method), a team of law enforcement and social workers summons likely shooters to sit-downs. At these call-ins, the suspects are presented with a choice between a swift arrest, if any more shootings occur, or counseling and job training to put their lives on a safer track.

St. Louis has actually already tried these tactics, too. Much of the funding for them came from the $1.7 million the city took in over a nine-year period through Project Safe Neighborhoods, an initiative born under George W. Bush that allowed cities to funnel the dollars toward either violence intervention programs or the hammer of stepped-up prosecutions. When the Obama Justice Department unveiled the Violence Reduction Network, offering 15 high-crime cities free consulting on best practices, St. Louis was a grateful participant in that new initiative as well.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

On the front lines in St. Louis, where financial constraints have left the police department operating 100 officers below its authorized force, officials are just grateful for the carousel of federal interventions. “I say thank goodness for all of it,” Leyshock says. “Because if we didn’t have that, how much worse would my problem be?”

But paradoxically, DOJ itself, through the Office of Justice Programs’ report, has a cutting assessment of why the different forms of federal assistance directed toward St. Louis haven’t made a bigger dent in its gun violence problem. The city’s crime-prevention efforts, the report concluded, have been hampered by a “lack of follow-up and sustained action.”

Cities like St. Louis desperately need federal crime-fighting support that is both customized and consistent, says criminologist David Kennedy of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. What they get instead is programs that ebb and flow as priorities change with new administrations and budget crises come and go. Most of the strategies that St. Louis has experimented with ran for short intervals, say two years, and were limited to a handful of neighborhoods.

“Unfortunately,” says Kennedy, simply, “there hasn’t been much federal support for the things that work.”

For all the free pointers St. Louis picked up through the Obama-era Violence Reduction Network (to be continued by the Trump administration under a new moniker, the National Public Safety Partnership), that program provided only technical assistance, and did not include money for local law enforcement to implement the tactics it recommends.

Trump’s 2018 spending blueprint called for reviving the moribund Project Safe Neighborhoods with a robust $70 million budget—but House appropriators chopped that down to $10 million. The Trump budget, meanwhile, is less generous with a line item that has paid for focused deterrence programs. The spending would be eliminated, for a savings of $8 million.

James Clark believes preventing violence requires changing behavior, not just prosecuting crime after it happens. It’s a concept that has support from the Office of Justice Programs, which recommended the approach in its report on St. Louis. And it is the foundation of a program that Clark runs at his nonprofit agency Better Family Life, working with crime victims and suspected shooters to head off violent conflicts. The strategy has a mixed record, but studies have shown that under the right circumstances this kind of outreach can discourage young men’s willingness to resort to violence.

“Now, in these neighborhoods, crime is both accepted and expected,” says Clark, a 50-year-old, muscular Army veteran with the cadence of an evangelist. “Now, it’s a culture where the people are saying, ‘I will kill you! I will shoot you dead!’ That’s a mentality. And the federal programs are not equipped to address the mentality.”

Clark prefers to hire former criminals to staff his small outreach team, a common tactic in violence-interruption programs, whose success depends on the credibility of their messengers. “They are the ones who can take that 12-, 13-, 14-year-old boy and mentor him out of his fixation with guns,” he says. “You have to meet them on the street corner, in the alley, at the barber shop, and you have to be able to change their life’s trajectory.”

Sometimes, Clark walks the blocks himself, asking residents what they’re hearing and seeing. On a mid-August Saturday morning, after making two of his regular weekly stops, at a church and community group, he headed to the Wells Goodfellow neighborhood to meet with a 17-year-old high school student. Ostensibly, he went there to drop off some money to help pay for shoes that the teenager needed for his school uniform. The gesture was an opening for his real and graver purpose: to chastise the student for posting a photo of himself on Facebook brandishing a gun.

Clark arrived to find three other young men hanging out on the stoop at the teen’s house. It offered Clark the sort of opportunity he and his outreach workers crave: a casual chat, “giving them the support that a man in my position should give them.” He reminded them, “You gotta be careful out here,” and commended them for staying out of trouble.

“I can say in no uncertain terms that all of them were good guys,” Clark says. That one of them had posed for a snapshot while holding a gun is to Clark not evidence of violent intentions, but rather of the desperate need such youth have for mentors willing to help them avoid danger.

Later that afternoon, Clark was relaxing at home when his phone rang. Over the sound of screams and moans, he heard the voice of the teen he’d sought out that morning.

“Mr. Clark, they came by shooting. We got shot,” the boy told him.

Clark raced to the scene, calling 911 on the way. The three other young men Clark met earlier had been hit in a drive-by. They limped out of the house “bloodied up” and piled into Clark’s truck to be rushed to a nearby hospital. They were treated and released by the next morning.

Five days later, Clark took another call, this time from a distraught woman. Her nephew, 18-year-old DeAndre Kelley, was one of the three casualties from the earlier drive-by. She started by thanking Clark for helping her relative.

Then, the woman said, “Mr. Clark, they’re dead, all of them.”

Clark was confused — the young men, he knew, had survived the shooting—but gradually he realized the woman was talking about another, newer attack.

On August 24, Kelley was one of four people slain in a north St. Louis County home. He had a job interview at a Target lined up for the same day. Police so far have no motive for the slaying. They describe Kelley and the others as “true victims” who simply lived in a place where senseless killings are commonplace.

Clark is certain the two shootings are unrelated. But they have provided him with a pointed reminder of the need to put more outreach workers on the streets, to intervene before more bullets fly.

As of last October, Clark was seeking $1.2 million in grants to expand his outreach team from 11 to 50 members. Now, it’s down to eight workers. Though he hasn’t entirely given up on securing some federal support, Clark now thinks he may fare better with private funders. “Things are going slow,” he says.

The killings are not. Through July 31, St. Louis has had 107 gun homicides, up 8 percent over last year—a new person shot dead in the city roughly every other day.

“We don’t need to study this no more,” Clark says. “We don’t need another case study. We are just sitting back and letting it happen.”