On Main Street in Man, West Virginia, a woman marched through the front door of Uncle Sam’s Loans, a cavernous pawn shop packed with hunting bows, fishing lures and camping supplies for the residents of this small Appalachian town. Behind the counter hung the linchpin of Uncle Sam’s business: guns.

The woman flashed her credentials, which revealed that she was an investigator with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, the nation’s gun industry watchdog. She was here to make sure Uncle Sam’s had cleaned up its act.

This was the ATF’s third inspection of Uncle Sam’s in seven years. The two most recent audits found that the store had transferred weapons without conducting background checks and failed to provide safety notices to handgun buyers. At one point, ATF records show, more than 600 firearms that should have been in stock could not be found — a red flag for gun trafficking.

In both cases, the violations were serious enough to warrant stripping Uncle Sam’s of its license to sell guns, according to ATF records. But agency officials decided to spare the shop, issue an official warning to its owners and give them another chance to prove they could follow the rules.

As the investigator leafed through handwritten ledgers in spring of 2014, she discovered that things had hardly improved. Sales records were incomplete, the store failed to report required information to law enforcement, and safety notices still weren’t going out. The inspector typed out her findings and sent them to her superiors.

Their decision: issue yet another warning.

Months later, the ATF learned that Uncle Sam’s was the backbone of a sprawling gun trafficking scheme. Witnesses told the agency that Steven Adkins, a longtime shop employee who’d purchased a stake in the business, had enlisted a host of people, including a colleague’s girlfriend and his brother-in-law, to falsify paperwork so it would appear they had purchased guns in legitimate transactions, according to court records. In reality, the guns were used to bribe coal officials in a pay-to-play scheme at a local mine. Others were sold on the black market, the witnesses said.

One accomplice told investigators “hundreds, if not thousands of firearms” had been trafficked through Uncle Sam’s. According to court records, he recalled parking his truck around the back of the store, loading up guns and delivering them to a convicted felon. Another accomplice said he drove guns from Uncle Sam’s to Adkins’s home, where Adkins allegedly sold them out of his basement.

Adkins pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting a false statement relating to purchases of more than 50 firearms from late 2008 to August 2014. He was sentenced to 10 months in prison. No one else was convicted in the trafficking scheme.

“Everybody knew where to get a firearm: Adkins,” said Roger D.B. Muncy, whose father founded Uncle Sam’s in 1975. “We’re all human, but you don’t send guns out the back door.”

The ATF is facing intense scrutiny as the Senate considers President Joe Biden’s pick for the agency’s first permanent director in six years. The confirmation of David Chipman, a former ATF agent who has advocated stricter gun laws, is unfolding against a backdrop of public anguish over mass shootings and a renewed determination from the White House to clamp down on easy access to firearms.

In one of the most sweeping examinations of ATF inspection records, The Trace and USA TODAY found that the federal agency in charge of policing the gun industry has been largely toothless and conciliatory, bending over backward to go easy on wayward dealers like Uncle Sam’s — and sometimes allowing guns to flow into the hands of criminals.

Gun industry lobbyists have fought for decades against tougher oversight by casting gun dealers as among the most heavily regulated businesses in the U.S. But The Trace and USA TODAY’s review found that dealers are largely immune from serious punishment and enjoy layers of protection unavailable to most other industries.

Reporters spent more than a year analyzing documents from nearly 2,000 gun dealer inspections that uncovered violations from 2015 to 2017. The reports showed some dealers outright flouting the rules, selling weapons to convicted felons and domestic abusers, lying to investigators and fudging records to mask their unlawful conduct. In many cases when the ATF caught dealers breaking the law, the agency issued warnings, sometimes repeatedly, and allowed the stores to operate for months or years. Others are still selling guns to this day.

More than half of all stores with violations transferred guns without running a background check correctly, waiting for the check to finish or properly recording the results. More than 200 dealers were cited for selling guns to people who indicated on background check paperwork that they were prohibited from owning them. Dozens made false statements in official records, a violation that includes facilitating illegal straw purchases.

A Florida gun dealer got in trouble for giving a Taurus handgun to a convicted felon in the parking lot and an Arkansas pawn shop was cited for selling a firearm to a customer even though he’d failed the background check because of an active restraining order. In Ohio, one store transferred guns without conducting background checks 112 times; another was missing some 600 firearms. A Pennsylvania gun retailer racked up 45 violations and received eight warnings from the ATF. But the store was allowed to remain in business, and went on to sell a shotgun to a man who used it to kill four family members, including his 7-year-old half-brother.

The reports were obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit by the gun control group Brady and shared with The Trace and USA TODAY reporters, who conducted an independent analysis. The reports detail inspections of brick-and-mortar gun stores and pawnbrokers, including home-based sellers, independent mom-and-pops and big box retailers like Walmart and Dick’s Sporting Goods. Others cover gun manufacturers and importers.

The data is extensive, but may not be comprehensive. The agency provided Brady roughly 2,000 reports from inspections that resulted in warning letters, warning conferences and license revocations over the two-year span from July 2015 through June 2017. However, annual fact sheets published by the ATF include aggregate figures showing the agency issued nearly twice as many penalties during fiscal years 2016 and 2017, a period that overlaps with the Brady documents.

The ATF repeatedly declined to explain that gap, but said it is investigating.

A single violation is enough to shutter a gun shop if ATF officials can prove that the store willfully broke federal regulations. In the vast majority of the cases analyzed by The Trace and USA TODAY, the ATF gave violators the lightest penalty available: a boilerplate warning letter reminding them that their compliance is critical to “reduce violent crime and protect the public.” The agency revoked a gun dealer’s license in less than 3 percent of cases.

Gun shop owners who violate the rules seem to understand that they have little to fear.

One owner told an ATF investigator that he was “busy” and didn’t “give a shit,” the agency records show. Another said he “did not like being told what to do.” The owner of a pawn shop in northeastern Kansas became “very belligerent and hostile” when questioned about falsifying records, shaking his finger in the investigator’s face as he told her to “do her job and stop messing with him.”

The ATF allowed all of those dealers to keep selling firearms.

Joseph Bisbee, a retired ATF agent in Seattle, said the lack of action has fostered a culture of impunity.

“There’s really no teeth to the laws, and gun dealers know that,” he said. “They can see that nobody gets prosecuted, that nobody gets held accountable, and that sends the signal that they can fudge things a little more and get away with it.”

The problems extend high into the management ranks of ATF. The Trace and USA TODAY’s review found that the managers of on-the-ground investigators routinely overrule recommendations to revoke licenses and order lesser punishments.

Reporters identified 138 reports in which ATF officials acknowledged that a dealer’s violations were severe enough for them to lose their licenses. The agency revoked 56 of those licenses, just over 40 percent. A majority were granted lesser penalties, ranging from temporary license suspensions to warning letters.

In the reports, ATF officials justified backing off by citing the dealer’s age, recent health problems, intentions to retire and, in one case, “affluent clientele.” One dealer got a pass because he had been in business less than a year; another because he had been in business for decades.

Sometimes, the agency was afraid that a dealer might sue. In 2017, an inspector advocated pulling the license for Back Acre Gun Works after reporting the gun shop west of Orlando, Florida, had falsified records related to the transfer of an AR-15-style rifle. A supervisor downgraded the penalty to a written warning, noting “substantial legal liabilities” because the inspection had been conducted “prematurely.”

Contact Us

Do you have tips or questions for the team behind this project?

Current and former ATF officials say the light regulatory touch is at least partly a reflection of Congressional restrictions on the agency’s enforcement powers. Some also say the ATF has increasingly adopted an industry-friendly approach to lessen the risk of a backlash that could lead to budget cuts or additional limits on its authority.

“They hardly do any inspections, and when they do carry out an inspection they shrug off serious violations and say they’re not a big deal because they don’t want to upset the industry too much,” said Mark Jones, who held various supervisory positions at the ATF before retiring in 2012.

The proliferation of gun retailers means there are bad apples in communities across America, ripe for targeting by criminals.

Kris Brown, Brady’s president, said the ATF “bends over backward to accommodate even the most egregious activity.”

“And Americans every day pay the price,” Brown said, “particularly Black and brown communities across this country that are being flooded with guns from these dealers.”

Goal is to gain compliance, not punish

The coronavirus pandemic, protests against police brutality and the election of President Biden spurred Americans to snap up an estimated 22 million guns in 2020, shattering records and reviving concerns about whether the ATF can adequately police such a booming industry.

“The most important part of the job is keeping the guns out of criminal hands,” said John Crecca, a former ATF inspector who worked in New York and Pennsylvania before retiring in 2011.

Crecca recalled the case of Bull’s Eye Shooter Supply, a gun store in Tacoma, Washington, that was sued by the families of victims of the 2002 Beltway sniper attacks, in which two gunmen armed with a Bushmaster rifle had shot and killed 10 people.

One of the Beltway gunmen told authorities he had stolen the rifle from Bull’s Eye. The shop hadn’t noticed the gun was missing until federal agents came calling. A subsequent ATF inspection found the store could not account for the sale of more than 230 other guns. Bull’s Eye settled the lawsuit for $2 million but did not admit liability for the shootings.

In the rare cases in which the agency decides to pull a license, the process is slow, often taking months or even more than a year to complete while dealers continue to sell guns. Sometimes, the ATF holds off on finalizing a revocation specifically to give the dealer time to sell off its remaining inventory, reports show.

The ATF is the main line of defense against firearms leaking out of legal streams of commerce and into the black market. The agency’s weaknesses have prompted Illinois, New Jersey, and a handful of other states to create their own gun store inspection programs.

In Illinois, the ATF held warning conferences with 1st Class Firearms in 2009 and 2013 after investigators discovered that the gun shop north of Waukegan had failed to conduct background checks, kept sloppy or incomplete records and illegally transferred weapons to out-of-state residents, records show.

Allowed to remain in business, 1st Class Firearms went on to sell at least a dozen weapons to a trafficking ring suspected of smuggling hundreds of kilograms of cocaine into the U.S. from Mexico, according to court records.

Inspectors returned in 2015 and cited 1st Class Firearms for 12 more violations. This time, agency officials determined that the store’s license should be revoked. According to records, one supervisor railed against the owner, Craig Bricco, for “displaying an intentional disregard and plain indifference to regulatory requirements.”

Bricco said in an interview that the problems at his shop were the fault of his employees, who ran the store while he was working another job during the day.

“I got bamboozled,” Bricco said. “There wasn’t much I could do.”

Instead of revoking his license, Bricco said the ATF allowed him to stay open for about six more months so he could sell off his stock of firearms.

Bricco voluntarily surrendered his gun dealer’s license after that period, but the agency let him remain in business as an ammunition manufacturer. He rebranded as 1st Class Ammo and transferred the shop’s leftover gun inventory to himself — a legal maneuver that enabled him to keep selling the firearms in private sales. In much of the country, private sales require no background checks.

In January 2016, 1st Class Ammo shared a Facebook post directing people to GunBroker.com, where Bricco was selling four Sig Sauer pistols.

“So it’s a private sale?” one Facebook user asked. “Yes, all private sales,” 1st Class Ammo responded, “you can see them on display in the ammo store.”

Some current and former ATF officials defended the inspection program as an effective way of ensuring gun dealers obey the rules without driving them out of business for fleeting missteps and unintentional errors.

Thomas Brandon, the bureau’s acting director from 2015 to 2019, said the goal is not to penalize gun shops and other federal firearms licensees but to gain their compliance.

“The high majority of FFLs are good hard-working people running businesses, and they’re our front line of defense for intelligence for diversion of firearms with straw purchases,” Brandon said.

Brandon, who now works in sales for a ballistics technology firm that contracts with the ATF and law enforcement, said the agency focuses its limited resources on “the one percent doing it wrong.”

In an emailed response to questions, ATF spokesperson Andre Miller portrayed the penalties as “tools to guide” dealers into correcting violations and “ensure future compliance.” He said the agency can revoke licenses only for willful violations and supervisors consider “the totality of the inspection and its unique circumstances to ensure consistent enforcement nationwide.”

“The nature of the violations and their impact on public safety, as well as ATF’s ability to reduce violent crime, are significant considerations for the appropriate action,” Miller said.

Dealers inspected once every seven years

A division of the Justice Department, the ATF is responsible for policing the 78,000 gun dealers, manufacturers and importers in the U.S. It employs more than 700 investigators who perform unannounced compliance reviews, digging through business records to make sure gun sellers are not providing weapons to people who shouldn’t have them.

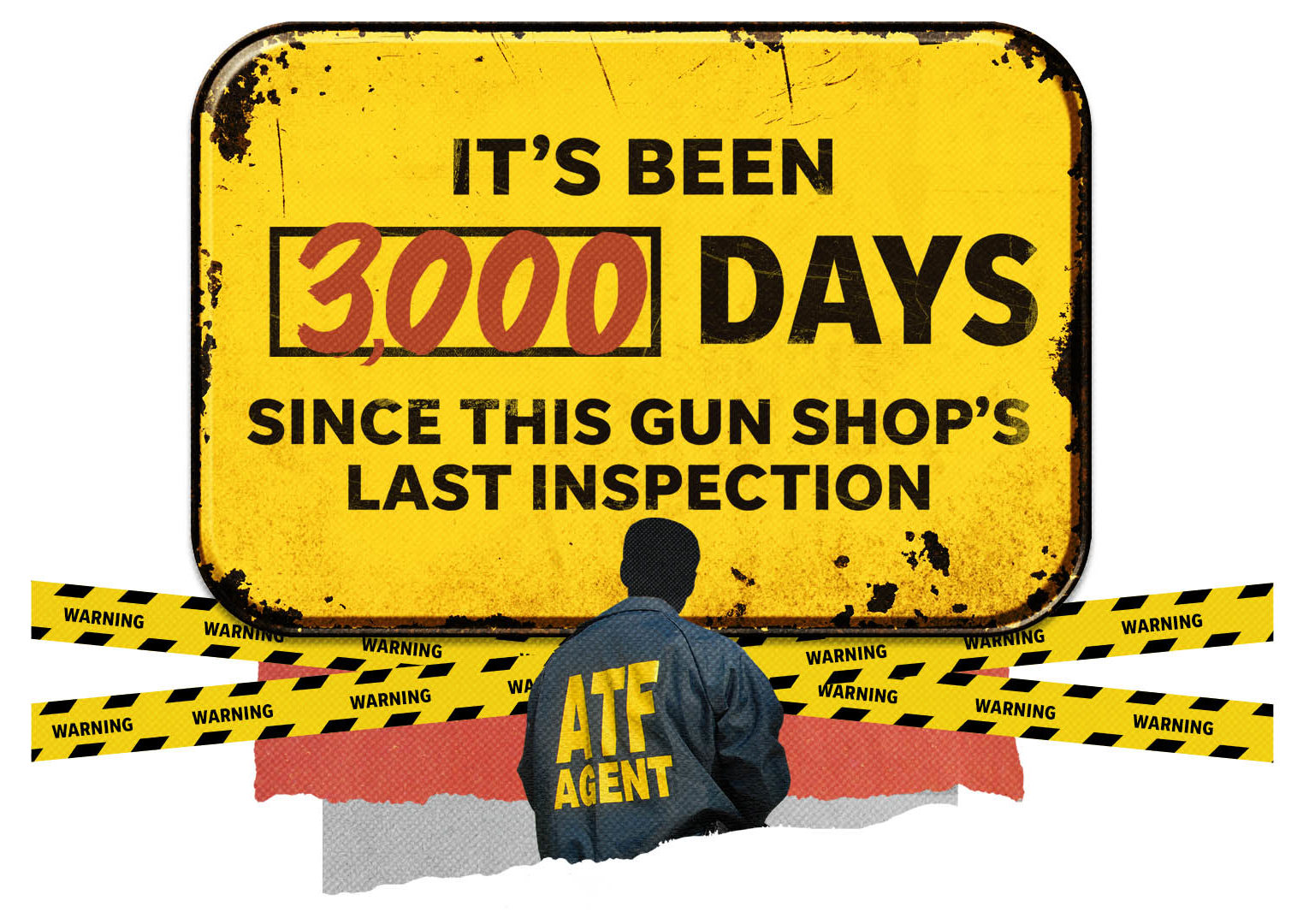

The goal is to inspect each license holder at least once every three years. But federal data shows the agency has averaged 15 percent of dealers annually between fiscal years 2010 and 2019. This means dealers were visited about once every seven years.

Of all the inspections during that decade, at least a third — 35,500 — found dealers had broken state or federal firearms laws, the agency data shows. More than 81 percent of violators received no penalty or a written warning. The ATF sought revocation of only 580 violators, or 1.6 percent.

In the 2020 fiscal year, as the coronavirus pandemic snarled government operations, the ATF inspected only 5,827 licensed dealers, or 7.5 percent — the lowest annual inspection rate since 2004. More than 2,400 of those dealers were found to have committed violations. Forty dealers had their licenses revoked.

The most common violations cited by the ATF were for gun sellers failing to acquire customers’ personal details, omitting information required on federal forms and not keeping proper inventory and sales records, according to the reports analyzed by The Trace and USA TODAY.

Former ATF officials and gun dealers said such violations are usually innocent mistakes stemming from the labyrinthine rules governing gun sales. But even seemingly minor paperwork errors can indicate a dealer’s involvement in more serious forms of lawbreaking, or can stymie law enforcement investigations into major crimes.

“Whenever you hear people say, ‘There’s plenty of laws on the books,’ there really aren’t. What there are are a lot of paperwork violations where you misrepresented something on a piece of paper,” said Scot Thomasson, the ATF’s former chief of public affairs. “But what each one of these paper violations represents is a crime, a crime gun and the diversion of firearms to the illegal market.”

Gun dealers almost never face criminal charges when violations are discovered in an inspection.

Former ATF officials attributed the agency’s permissive regulatory approach to longstanding staffing and funding shortages as well as federal laws that shield the gun industry from accountability. Over the last 35 years, gun groups have successfully pressured Congress to limit the frequency of inspections, restrict the ATF from consolidating and computerizing records, and make it more difficult for the agency to take dealers’ licenses away.

In 1986, the National Rifle Association successfully lobbied for the passage of the Firearm Owners’ Protection Act, which prevents the ATF from inspecting existing gun dealers more than once a year. After 9/11, Congress required that the ATF audit each of the nation’s 9,400 explosives dealers once every three years — effectively forcing it to deprioritize inspections of gun dealers. The number of gun dealer inspections plunged, falling from an average of nearly 12,000 inspections a year in the 1990s to less than 7,000 a year in the 2000s.

“ATF is a very small agency, a very unpopular agency, and as a result, there are a lot of people trying to push them around,” said Howard Wolfe, a former ATF supervisor who oversaw inspections in Pittsburgh until he retired in 2006.

Wolfe said the investigators under his command would need to have visited multiple gun shops every day to meet the ATF’s inspection goals.

“There was no way,” Wolfe said. “People went years without being inspected, and that’s a big problem, because how do you know how somebody’s doing if you don’t have a chance to go out and take a look at their records?”

ATF investigators spent an average of 84 hours on each of the inspections examined by The Trace and USA TODAY. One particularly taxing case, in Houston, took 995 hours, the equivalent of half a year of workdays. The investigator recommended revoking the license, but was rebuffed by the industry operations director, who cited the “length of time taken to complete the assignment.”

In another case, in Kansas, a business called A Pawn Shop transferred an AK-47-type rifle and a Glock to a woman acquiring the weapons on behalf of her boyfriend, a convicted felon, court records indicate. In February 2016, he used those guns to shoot 17 people in a rampage across the towns of Newton and Hesston.

An ATF inspector visited A Pawn Shop several months later and found the store had failed to obtain proper IDs, sold a handgun to a self-identified domestic abuser, and hadn’t been ascertaining whether its customers were straw purchasers, according to an agency report. The ATF downgraded the penalty to a written warning because the store had never received an inspection in its six years of business.

“Had the ATF gone in there and done an inspection earlier it might have caused this shop to clean up its act. It might have prevented a mass shooting,” said David Morantz, an attorney who represented one of the Hesston shooting victim’s surviving family members in a wrongful-death lawsuit against the shop. The lawsuit resulted in a $2 million settlement. The shop is now closed.

Teresa Ficaretta, a former senior ATF attorney who went into private practice helping gun industry clients comply with the law, said limited resources had led the bureau to focus on inspecting dealers who sell large numbers of crime guns, frequently transfer large quantities of firearms to a single customer or raise other red flags.

Ficaretta said that was a poor substitute for regular inspections and could embolden dealers willing to break the law.

“If licensees knew that ATF was going to show up like clockwork, they would put a lot more effort into maintaining compliance,” she said. “But right now there’s this incentive for them to roll the dice and see what happens.”

The size of the ATF’s inspections staff has been stagnant for decades. In early 2016, after a mass shooting at a holiday banquet that killed 14 people in San Bernardino, California, the Obama administration rolled out a gun violence prevention plan that included a request for nearly $12.3 million to add 120 ATF investigators. The Republican-controlled Congress balked, with one GOP member of the House Appropriations Committee saying lawmakers would not support “the development of unlawful limitations on the unambiguous Second Amendment rights of Americans.”

B. Todd Jones, a former U.S. Attorney who served as the ATF’s last Senate-confirmed leader before resigning in 2015, said that, despite the “20-plus years of regulatory handcuffs,” investigators work hard to balance compliance and the adversarial relationship needed to provide oversight.

“We did our best to plug holes and stop the worst offenders,” said Jones, who is now chief disciplinary officer for the NFL. “It’s like setting up a speed trap: You’re not going to stop everyone. And if you get caught speeding, you have to deal with it. But what’s the alternative? No regulation at all?”

During delays, guns end up in wrong hands

The ATF investigators who inspect gun stores do not carry badges or guns and cannot make arrests. They can recommend hitting problem gun stores with penalties, known as “adverse actions,” but the ultimate outcome of an inspection depends heavily on directors of industry operations, who make the final call.

The Trace and USA TODAY found wide variation in the penalties handed down by field divisions.

For example, at the Louisville field division — which covers Kentucky, West Virginia, and southern Indiana — reporters identified 12 cases in which investigators found that a dealer’s violations warranted revocation. Nine of those recommendations were approved by the division’s industry operations director.

In contrast, the industry operations director for the Seattle field division — which covers Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Alaska, Hawaii, and Guam — approved only one revocation out of the seven recommended by investigators.

Jim Zammillo, a former ATF deputy assistant director who oversaw the inspection program from 2004 to 2010, said the Justice Department’s inspector general and other agency watchdogs had repeatedly faulted the bureau for applying adverse actions inconsistently, prompting it to initiate a series of improvements beginning in the early 2000s.

Chief among the reforms was a new set of guidelines establishing the minimum penalties to be issued when violations were found. The guidelines specified that penalties should increase for repeat offenses, and any field division wishing to spare a dealer from revocation had to get approval from headquarters.

The increased oversight led to greater standardization, Zammillo said, but it also caused consternation among field division heads. “They viewed it like, ‘I’m the sheriff, this is my department, and I’m going to run it the way that I want to,’” Zammillo said.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

John Jarowski, a former industry operations director in St. Paul, Minnesota, offered another explanation, saying downgrades to less serious punishments help temper strict investigators.

“Inspectors go in and they want the kill. They want the scalp on their belt,” Jarowski said.

Proprietors who receive a final revocation notice have 60 days to file an appeal in federal court, a costly process that often just delays the process for months or years. U.S. Attorneys represent the government in those cases on behalf of the ATF.

“Many times when the U.S. Attorney steps in he’d say, ‘This dog won’t hunt,’ and they’d drop it,” Jarowski said. “So you have to think about spending your resources wisely.”

In many areas of civil and criminal law, defendants cannot use ignorance as an excuse for unlawful behavior. When it comes to gun sellers, Congress has stipulated that they can lose their licenses only for violations committed willfully, forcing the ATF to prove that dealers knew the rules and intentionally disregarded them.

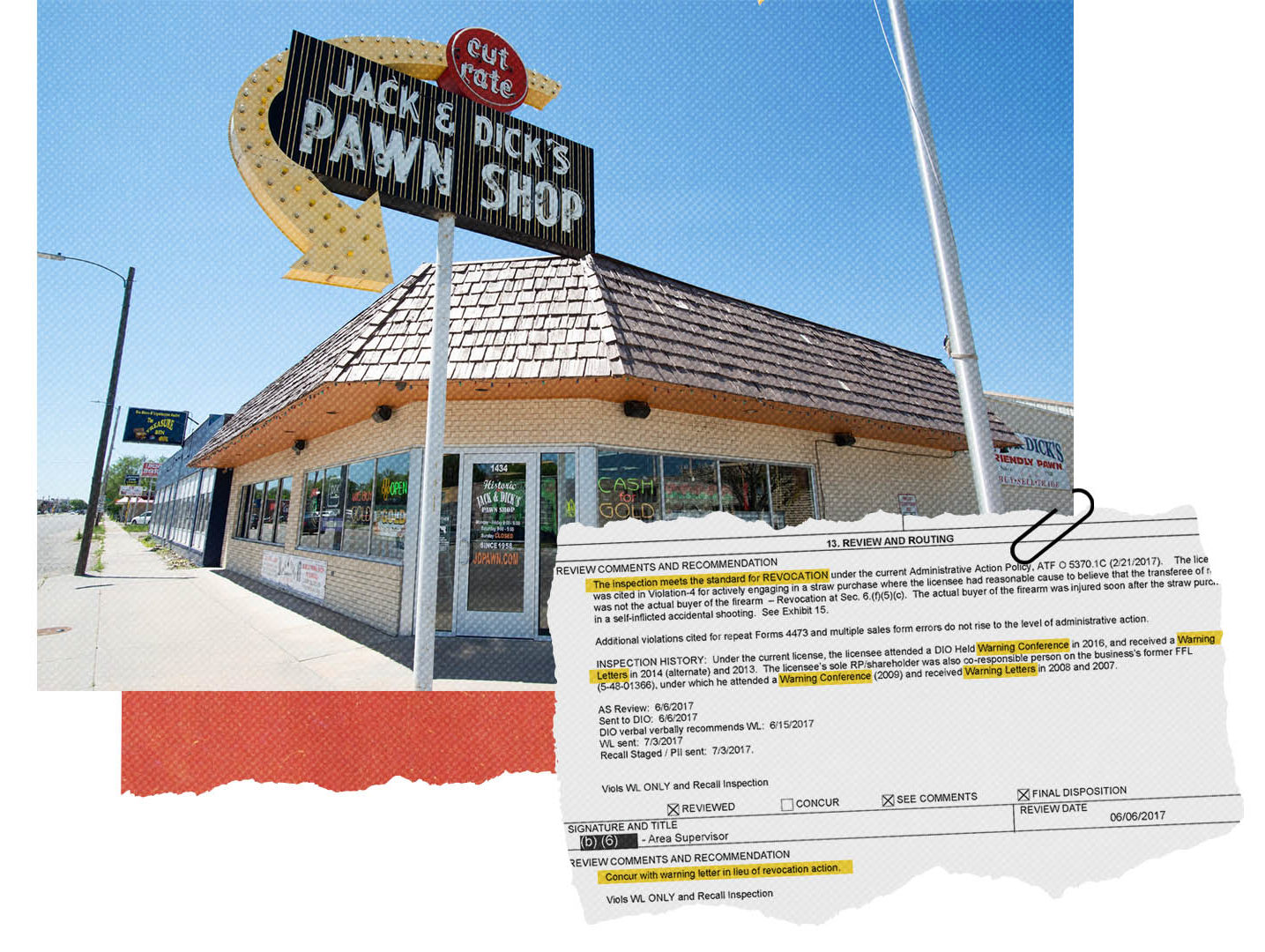

Jack & Dick’s Pawn Shop in Junction City, Kansas, received warning letters in 2013 and 2014 and attended a warning conference in 2016. When the ATF returned in 2017, it uncovered four additional violations, including making false statements in required records, a report shows.

The false statements charge stemmed from the case of a Fort Riley soldier who’d accidentally shot himself in the hand using a pistol from the shop, according to a police report. The soldier, 20, was underage for handgun purchases in Kansas. He had had a friend fill out the paperwork.

ATF records indicate the investigator pushed to revoke Jack & Dick’s license based on evidence that the shop had ignored obvious signs of a straw purchase, including when the friend paid by using the soldier’s credit card. The investigator was overruled by higher-ups, who said it wasn’t clear whether the employee knew he had accepted the wrong credit card.

The ATF decided to give Jack & Dick’s another written warning. The owner of the shop declined to comment for this article. In 2017 and 2020, the shop released surveillance photos and video on its Facebook page of other attempted straw purchases in an effort to expose the crime.

When the ATF does decide to revoke a dealer’s license, the agency’s delay in putting the penalty into effect can allow guns to wind up in the wrong hands.

JC’s Guns & Tackle Shop in Huntsville, Alabama, received its first compliance inspection in 2013, resulting in a warning conference. Investigators returned two years later for a second inspection that uncovered 13 violations, six of them repeated, according to an ATF report.

The shop had failed to report multiple sales, falsified forms and sold guns to people who’d self-identified as being prohibited. It failed to conduct background checks on customers but did use the background check system to screen employees, which is illegal, the report indicates.

Investigators also discovered that employees had facilitated multiple straw purchases, selling weapons to stand-ins when background checks on the actual buyers were delayed.

It took the ATF 16 months to revoke JC’s license. During that time, according to court records, the shop sold 11 handguns to a straw purchaser buying them on behalf of her boyfriend, a convicted felon.

Officials cite dealer ignorance to justify leniency

Gun store owners offered the ATF a litany of excuses to explain away violations.

The agency spared a Nebraska pawn shop from revocation after the owner said he was “very busy and overwhelmed.” A Pennsylvania sporting goods store was allowed to keep selling firearms despite being cited three times in four years for failing to report multiple handgun sales. During the last inspection, in 2016, the owner told an ATF investigator he meant to file the reports “but did not get around to it.”

Felex Yukhtman said he trusted the “wrong people” to manage his small gun manufacturing business in Bradenton, Florida. Yukhtman’s company, Gun Point, specializes in building custom ARs. In 2017, an ATF supervisor upheld an inspector’s recommendation to shut Yukhtman down after a review of his books turned up 15 violations. They included the possession of illegal machine guns, later seized by agents. Yukhtman was also missing 250 firearms, he said in an interview.

The supervisor criticized Yukhtman for having “shown a pattern of repeated violations” despite the ATF “educating the licensee through every inspection and through every warning conference since 2008.”

The industry operations director overturned the recommendation and summoned Yukhtman in for another warning conference. Yukhtman says he believes he was spared because he reached out to the ATF for advice and put in place safeguards to prevent further mistakes.

“They’re not there to take your license or make your life miserable,” Yukhtman said. “The less work they have to do at your store, the less time they have to be there, the better it is for them.”

To obtain a federal firearms sales license, applicants have to mail in their fingerprints and a photograph along with a four-page form containing basic business and biographical information. The form also requires applicants to check a box to indicate whether they have a felony conviction, were ever committed to a mental institution or are otherwise precluded from possessing firearms.

The price of a firearms license ranges from $30 for vintage gun collectors and ammunition manufacturers to as much as $3,000 to sell strictly regulated weapons such as mortars and grenades. The license held by many retail gun dealers costs $200 for the first three years and $90 for every renewal.

Applicants do not have to undergo training or pass a test. The ATF instead has dealers sign a document attesting to their knowledge of gun laws and regulations before opening for business.

Still, ATF officials have routinely pointed to dealer ignorance to justify leniency. A dealer in Pounding Mill, Virginia, avoided a warning conference after expressing “his apparent shock,” according to a report, at learning of the requirement to report customers who made back-to-back handgun purchases.

The National Shooting Sports Foundation, the gun industry’s trade group, works with the ATF to educate license holders about how to stay within the bounds of the law and prevent illegal trafficking.

“By and large, firearm retailers are law-abiding and follow local, state, and federal authorities,” said Mark Oliva, a National Shooting Sports Foundation spokesman. “We’re members of our community, mom-and-pop shops committed to keeping our communities safe.”

The foundation recruits consultants and former ATF inspectors to put shops through mock inspections. For $750, the organization will run a full-day compliance check that produces a confidential report of shortcomings. It also runs a hotline for retail federal firearm license holders, which Oliva said receives hundreds of calls a year.

But Rich Marianos, a former ATF assistant director, said the foundation is committed to keeping regulation as weak as possible. In 2020, it spent $4.5 million on lobbying, more than twice as much as the National Rifle Association, which spent $2.2 million, according to OpenSecrets.org, a nonpartisan research group that tracks money in politics.

“They’re like the NRA,” Marianos said. “Never once have they said the ATF needs more money, help, support or resources.”

Oliva disputes that characterization. He provided confidential records of the group’s lobbying of Congress in recent years to add millions for ATF’s licensing system and millions more to improve criminal background checks at the Department of Justice.

The legacy of Uncle Sam’s

The call that started the unraveling of the gun trafficking operation at Uncle Sam’s in West Virginia came in April 2015.

The girlfriend of a former employee contacted an ATF agent to say that she had learned her name had been wrongfully listed in the store’s records as the purchaser of shotguns, rifles, and a pistol. According to court records, she later told an ATF agent that Steven Adkins had paid her $75 each time she filled out a background check form for a firearm destined for another person.

It was a scheme Adkins had been running for at least six years, and he’d kept it hidden from the ATF even though investigators had inspected the shop over that time frame.

After being indicted in late 2015, Adkins told the ATF that he had hatched the gun trafficking arrangement at the behest of the store’s founder, Roger D. Muncy. According to court records, Adkins claimed Muncy became furious at employees for blocking gun sales, and if customers indicated on the federal form that they were prohibited from purchasing firearms, Muncy had them fill out a new form and instructed them how to record their answers so that the sale could go through.

Adkins estimated that 70 percent of the gun sales at Uncle Sam’s were illegal.

The case reverberated across the small town of Man, where Adkins and Muncy were serving on the City Council. In 2008, the city had renamed a street in Muncy’s honor.

Adkins pleaded guilty in 2016, and the ATF pulled Uncle Sam’s gun license. Adkins, who has since been released from prison, declined requests to be interviewed for this article.

Muncy was never charged, but the revocation didn’t stop him from profiting from guns. After losing the license to sell firearms at Uncle Sam’s, he rented the store to a state trooper, who obtained his own license and continued running a gun shop at the location. The arrangement lasted until July 2019, when the two parties had a falling out.

In his testimony, Muncy denied wrongdoing in the Adkins case. He went on to operate Uncle Sam’s as a pawn shop until he died in December at the age of 68. His wife died four days later. Since then, the day-to-day management of the store has fallen to their son, Roger D.B. Muncy, who hopes to get back in the gun business.

“The day my daddy and mommy died, I was calling Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms wanting to know if I was able to get a firearms license,” he said. “They said I need to file my application.”

The team behind the Off Target project

Reporting and analysis

Champe Barton, Allegra Cullen, Brian Freskos, Daniel Nass, and Alain Stephens, The Trace; Dan Keemahill, Nick Penzenstadler, and Steve Suo, USA TODAY

Editing

Amy Pyle, USA TODAY; Miles Kohrman, Tali Woodward, The Trace

Graphics

Craig Johnson, USA TODAY; Daniel Nass, The Trace

Illustrations and digital design

Andrea Brunty, USA TODAY

Photography

Emily Johnson, Evert Nelson, Chris Powers, USA TODAY

Digital production and development

Chris Amico, Ryan Marx, Annette Meade, Mike Stucka, Reid Williams, USA TODAY

Social media, engagement, and promotion

Nicole Gill, Hayley Hoefer, Chrissy Terrell, Katie Vogel, USA TODAY; Gracie McKenzie, The Trace