President Joe Biden’s failed pick to lead the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives says the ugly and personal confirmation process hardened his resolve to focus on gun safety and push back against the industry’s outsize influence on the agency — even if he has to do so from the outside.

David Chipman, whose nomination to lead the ATF collapsed earlier this month following a bitter confirmation battle, said he received little backing from the White House or the Department of Justice even after a massive lobbying campaign erupted against him.

Chipman said his political fight was minor compared to what victims of gun violence have experienced, including U.S. Representative Gabrielle Giffords, who endured brain injuries from an assassination attempt in 2011.

“I have the choice of buying a lake house somewhere and turning off social media and saying I give up,” Chipman said. “What am I going to tell Gabby? She’s still getting out of bed every day. What do I say? ‘This is too hard for me?’ I wasn’t shot in the head.”

Chipman, 55, said he looks forward to continuing his work at Giffords, where he has held the position of senior policy advisor for five years. The organization was founded by the former Arizona congresswoman to fight gun violence.

Chipman spoke out this week in his first interviews since the president pulled his nomination on September 10.

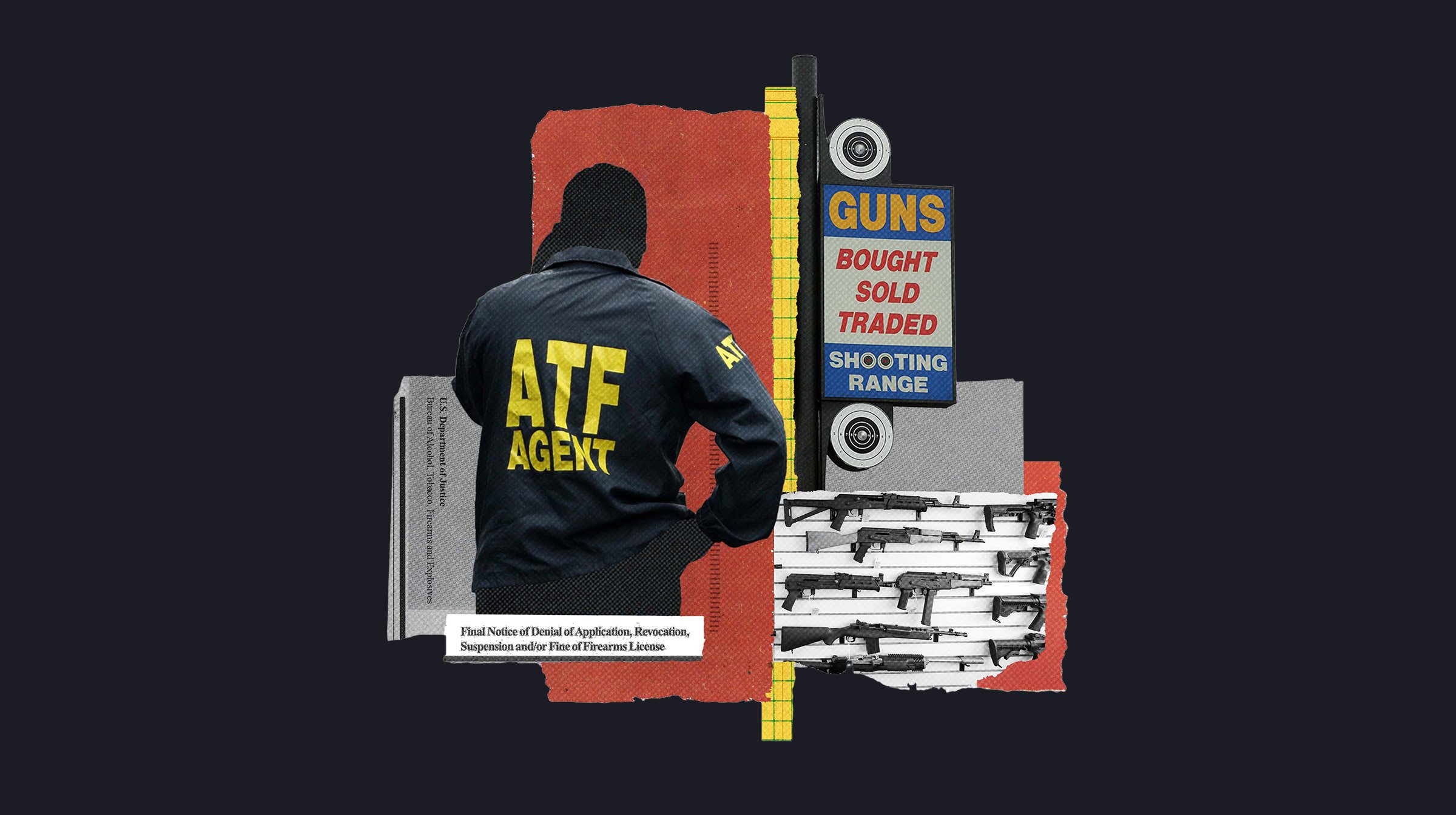

Chipman said the ATF should be renamed “After The Fact” because it has long been too reactive in combating gun crime instead of keeping firearms away from people prohibited from owning them. He had hoped to chart such a course as director, but the gun industry persuaded key U.S. Senators to sink his nomination.

“The agency isn’t rudderless. It’s sailing with a rudder set by the industry itself. Things are going just as planned: Target bad guys with guns, play nice with the industry, focus on things after the fact,” Chipman said. “You want them to have one mission: Protect the public. Period.”

Senate Republicans pressed Chipman at his July confirmation hearing about his views on banning assault-style weapons and other polarizing gun policies. He says he now realizes those questions were a trap to extract sound bites — to be used by conservative fund raisers — regarding restrictions, many of them outside the purview of the ATF director.

“It was purposeful theater,” Chipman said, adding that the White House instructed him not to worry about GOP senators’ views because none of them were going to vote for him anyway. “Your goal is to make sure all Democrats feel comfortable voting for you,” he recalled being told.

He faced scrutiny about his previous comments on restricting use of AR-15s and poking fun at new gun owners. And he faced a bevy of potent allegations — including some tying him to the 1993 siege at Waco, Texas — that proved false.

Despite a series of practice sessions with DOJ staffers, Chipman believes both he and the White House should have done more to prepare for scrutiny.

“There’s no second-place trophy,” he said. “I did not become ATF director, and I hold part of that responsibility, but I certainly tried my hardest.”

Even with limited regulatory power as ATF director, his posture toward the industry and gun owners would have run afoul of most Republicans who back expansive views of the Second Amendment.

Chipman said if he had been confirmed he would have redoubled efforts to combat gun trafficking by focusing the ATF’s limited resources on policing gun dealers with lengthy track records of violations. He pointed to a USA TODAY/The Trace investigation that showed the ATF routinely went easy on dealers even after they repeatedly broke the law.

Out of all gun dealer inspections conducted by ATF between 2010 and 2019, at least a third — 35,500 — unearthed violations, the investigation found. Dealers sold weapons to convicted felons and domestic abusers, lied to investigators, and fudged records to mask their unlawful conduct. In more than 81 percent of instances, violators received no penalty or written warning. The ATF sought to shut down only 580 violators in that timeframe — 1.6 percent.

Chipman criticized the ATF for becoming too close to industry groups like the National Shooting Sports Foundation, which represents the firearm manufacturing and sales industry.

The NSSF does partner with the agency to offer rewards for information about gun store burglars and to educate shops about preventing illegal firearm purchases. But Chipman pointed out that the group had opposed mandatory gun store security measures and other proposed laws that could go much further to ameliorate those problems, and he blamed its cozy relationship with the ATF for stymieing the agency’s ability to hold bad dealers accountable.

“The primary mission of ATF compliance operations cannot be as a PR agency for the gun industry,” Chipman said. “If you get a dirty dealer, that’s a real problem, and crime guns fall out of there. But the only way you know if someone’s being dirty or not is you got to act like investigators and you got to get in there.”

For its part, NSSF spokesman Mark Oliva said his group had urged the Biden administration to nominate “an individual who can administer the laws and regulations governing the firearm industry and the exercise of Americans’ God-given Second Amendment rights without bias or predisposition.”

Chipman, Oliva said, was not that person.

The ATF is among the nation’s smallest federal law enforcement agencies with about 5,000 employees. Groups like the National Rifle Association, with millions of members and powerful industry ties, and others have lobbied for years to keep the agency’s regulatory touch as light as possible, including by blocking permanent directors, said Jim Kessler, an executive vice president for Third Way, a center-left think tank in Washington, D.C..

“NRA’s goals have been to keep ATF alive, but make it as sick and weak as possible and saddle it with regulations,” Kessler said. “They oppose any director that has even a tinge of anti-gun sentiment or is seen as a tough, law-and -order guy or gal.”

Chipman became a lightning rod for his previous posture toward new gun owners. He said in some ways his failed nomination will liberate him to continue advocating at Giffords on behalf of gun violence initiatives.

“I volunteered to drive the bus, you didn’t want me to drive, so now I’m just a passenger, and I’m going to be loud,” he said.

‘No one was fighting for me’

Chipman was washing dishes one night when Attorney General Merrick Garland called to tell him he was Biden’s choice. In April, Chipman and his family watched as Biden made the announcement on national TV, with the president calling him “the right person at this moment for this important agency.”

It was a thrilling moment. After 25 years at ATF, Chipman had retired in 2012 and went on to work as an advisor to organizations that advocate gun control. He knew his many public statements supporting tougher gun restrictions would make him persona non grata among gun rights supporters, but he expected the full-throated support of the White House’s political machine and detailed policy briefings from DOJ staff to steer him through a Senate confirmation that was anticipated to be brutal.

Instead, he said, he got neither.

As waves of personal attacks from the gun industry and a misinformation campaign fueled by viral memes went unanswered, Chipman found himself alone, with no contact with the White House. His only support was a DOJ staffer who coordinated appointments with Congress.

He said never spoke with Biden himself.

The White House directed Chipman not to respond to the rhetoric out of fear it would only fuel more chatter. In retrospect, Chipman said that was bad advice, fueling the misinformation to spiral further out of control.

“It has been a battle unlike any one I’ve ever waged in my professional or personal life,” Chipman said. “At times, it felt riskier than when I was on the ATF SWAT team.” It began Day One, he said, with a protester appearing at his suburban Washington, D.C., home hours after his nomination was announced.

One particular galling claim was over Chipman’s participation in the bloody 1993 government siege of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas. A viral photo of a camo-clad federal agent identified as Chipman, standing in the rubble, circulated widely online after the nomination and made him the target of death threats.

When no one in the Biden administration set the record straight, Chipman himself dug through curled fax records in his storage shed to prove to a news fact checker that he wasn’t in Waco when the photo was taken. He had arrived at Waco only weeks later to investigate the incident.

Late in the confirmation fight, opposition research groups surfaced complaints of discrimination from some of Chipman’s former ATF colleagues. The issues had already been disclosed to a DOJ vetting team and senators, but as the controversy grew, the White House remained mum, leaving Chipman again feeling defenseless.

Chipman said two of the complaints came from subordinates who were upset after he disciplined them for being frequently tardy. The other involved Chipman voicing concerns about possible cheating on ATF promotion exams after he found an agent had given answers strikingly similar to ones contained in the guide used to grade the tests. The agent was Black, but Chipman emphatically denies that race played any role. The employment complaints were resolved without any finding of discrimination and no disciplinary action.

“There was no way I would have made it out of ATF honorably if there was merit to any of that,” Chipman said. “My frustration was that DOJ knew all of these facts and could have put a quick end to it. It hurt me personally.”

Biden announced Chipman’s nomination in April along with a slew of executive actions to crack down on homemade, unserialized “ghost guns” as well as pistol-stabilizing braces, an accessory used weeks before in the killing of 10 people at a Boulder, Colorado, supermarket. The president followed up in June with an initiative to crack down on problem gun dealers and increase resources for law enforcement and community-based anti-violence programs.

Any ATF director nominee Biden put forward was bound to be controversial, but Chipman proved especially polarizing. During his May confirmation hearing, GOP members of the Senate Judiciary Committee lambasted the former agent for his gun-control advocacy.

Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the committee’s top Republican, said giving Chipman reign over the ATF was “like putting a tobacco executive in charge of Health and Human Services or antifa in charge of the Portland police department.”

Republicans also took issue with Chipman’s past statements on firearm ownership, including one where he allegedly mocked people who had purchased their first gun because of the COVID-19 outbreak by telling them to keep their weapons hidden behind beef jerky and cans of tuna until the zombies appeared.

Chipman told the committee the statement was an attempt at self-deprecating humor. “The person who had a gun stored behind his tuna and beef jerky was me,” he said.

In early September, it all came to an abrupt halt when Chipman received a call from White House adviser Steve Ricchetti. His nomination, Ricchetti said, was being pulled.

Chipman’s failed bid dealt a blow to the White House’s gun violence prevention efforts after the nation endured a 29 percent spike in murders in 2020 — the largest one-year change since the federal government began compiling national figures in 1960.

The ATF has had only one confirmed director since 2006, when the gun lobby swayed Congress to strip the president of the power to appoint the agency’s director without Senate approval.

“This system is designed for us not to have a robust head at the helm of ATF. The fact that we’ve only had one since it became a Senate-confirmable position is an indication of that,” said Igor Volsky, executive director of Guns Down America, part of a coalition of groups pressing Biden to create a gun violence prevention office headed by a cabinet-level staff member.

But Volsky said the White House’s failure to muster the kind of campaign needed to secure Chipman’s confirmation showed that gun violence prevention was not truly a high priority for the president.

“Anyone who’s worked on this issue for any length of time or who’s frankly observed modern politics over the last several years should not have been surprised that there are bad actors from the NSSF on down who would use as an opportunity to ensure there was no one at the top to regulate the industry,” Volsky said. “They had not at all prepared for the kind of fight that ensued.”

Asked about the situation during a briefing earlier this week, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said the administration shared Chipman’s frustrations over him not being confirmed. But she disputed his claim about the administration’s lack of support.

“There was a whole team of multiple people behind him,” Psaki said. “We engaged with members of the Senate, including the president. Unfortunately we didn’t have the votes.”

Contributing: Joey Garrison, USA TODAY