On a December afternoon in 2018, Hamid Abd-Al-Jabbar pulled into the parking lot of a McDonald’s on Milwaukee’s north side. Overhead, under the company’s iconic arches, the ‘M’ was smashed out. A stretch of cracked pavement connected the restaurant to the headquarters of 414LIFE, the violence prevention nonprofit where he worked.

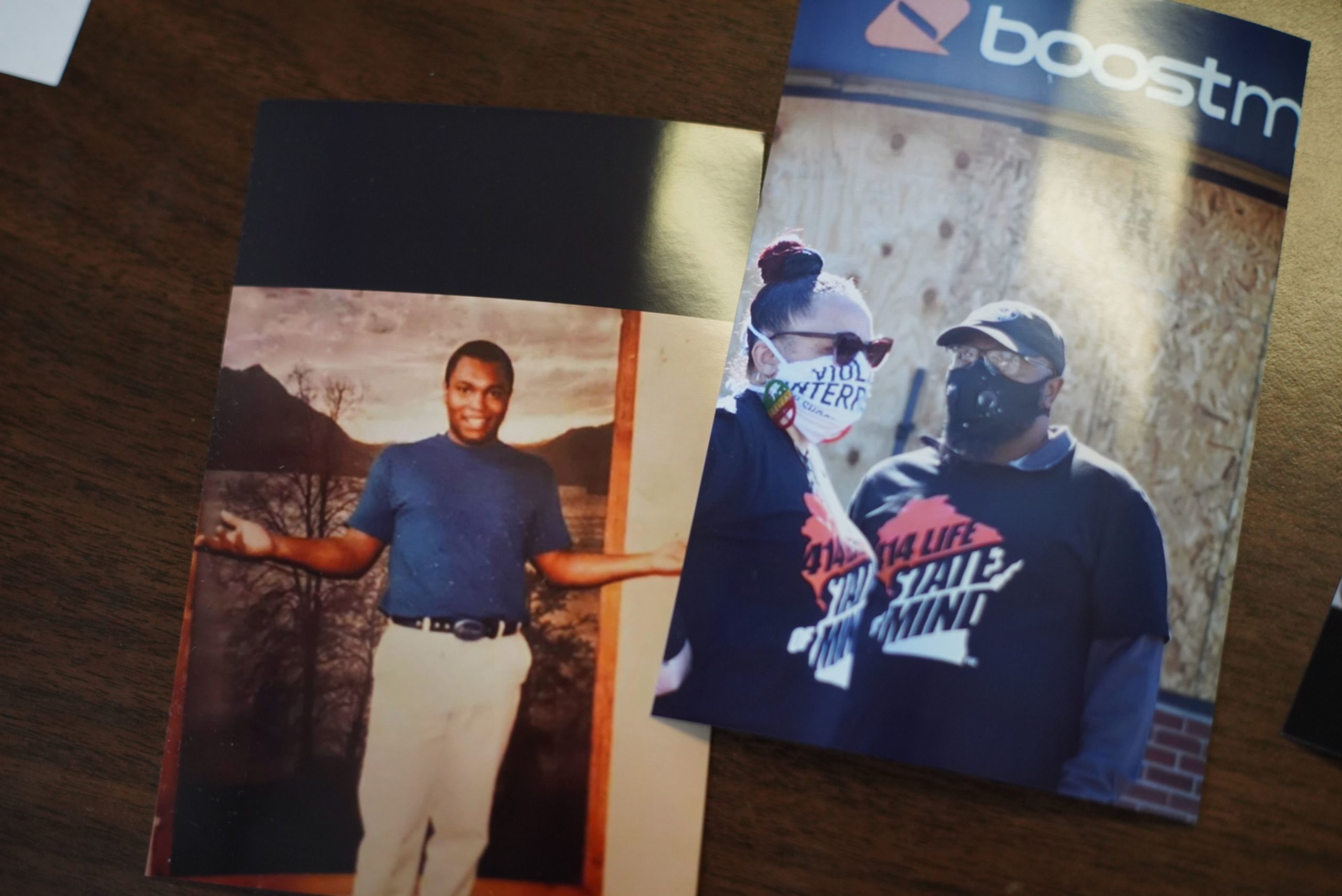

Jabbar had plans to meet a client for lunch. As he waited in his car, he chatted on the phone with his wife, Desilynn Smith. The pair were high school sweethearts, whose relationship had weathered 27 years in prison and numerous splits and rekindlings.

Since his first arrest at 18, Jabbar had never been out of prison for more than a few years at a time. He was 50 now. In only five months free, he had made significant strides, marrying Smith in a small courthouse ceremony and securing part-time work with 414LIFE. But he knew well enough that stability could be tenuous.

After a few minutes, his client pulled into the next parking space. Jabbar switched off his ignition and stepped into the cold, cradling the phone between his ear and shoulder. He noticed his client held a hand behind his back as they greeted. Before he could wonder why, the man drew a gun and shoved it in Jabbar’s face.

On the other end of the line, Smith overheard the man demanding money. Jabbar abruptly ended the call. He insisted he had nothing, locked his car, and threw his keys into a scraggly bush nearby. His client threatened to shoot, then retreated to his car and sped away.

Seething, Jabbar trudged to the bush and rifled for his keys. Reminders of his past were hard to avoid — Jabbar had pistol whipped the man over a drug debt a few decades earlier. He felt his freedom was again in danger.

Jabbar called a different client, an old friend named David Thompson, and said that he needed a gun.

A changing city

Wisconsin incarcerates Black men at a higher rate than any state in the country, according to a 2013 study from the University of Wisconsin. In downtown Milwaukee, reminders of this reality are scarce: wide, paved streets, vintage marquees, and street lanterns give the city a quaint, small-town feel. To the north, squat brick and clapboard homes preserve the quiet dignity of the homeowners who purchased them in the 1950s and 60s, when the city had a robust Black middle class. But the neighborhood’s main commercial corridor, along Capitol Drive, contains dozens of boarded-up businesses and smashed facades.

As a young child in the early 1970s, Jabbar — born Earvin Reeves — would not have predicted this decline. His mother and stepfather owned their home: a red brick single-family with bay windows and a two car garage. They had a backyard big enough for Jabbar’s stepfather to construct a citizen’s band radio tower that was taller than their house and interfered with nearby television signals.

Milwaukee in those years led the nation in blue-collar employment among Black people, with 43 percent employed as industrial laborers, according to the 1970 census. The city was known as “The Machine Shop of the World.” Jabbar’s stepfather worked at a local tannery and the work fit his personality well — it was physically demanding and required orderly persistence.

Those same traits irked Jabbar at home. Jabbar adopted little of his stepfather’s perfectionism or stick-to-itiveness. He struggled in class and, by middle school, he had developed a penchant for petty theft. Because his parents were well-to-do, and because the city still felt so prosperous, the risks weren’t immediately apparent. So when Jabbar began hanging out with neighborhood kids into the late hours of the night, his parents didn’t think much of it. And when he took an interest in BMX biking, they encouraged the fun, fitting him with high-end models from Mongoose and Diamondback.

During the neighborhood hangouts Jabbar found brothers and father figures who weren’t disappointed by his missteps in the classroom. But he and his friends caught the attention of kids from other neighborhoods, some of whom would, every so often, steal their bikes. To protect against theft, the boys formed what they referred to as a gang. They called themselves the BMX Boys, and later the 2-4s, for North 24th Street, where many of them lived.

Other neighborhood groups labeled the 2-4s “uppity,” and the boys fought frequently to prove their mettle. In the winter of 1983, after a devastating recession, a handful of manufacturing plants had to make cuts, and gangs grew, bloated with men freshly out of work. Jabbar and Thompson, hardly aware of this development, were at Palace Roller Rink, a colossal skating venue, when a fight broke out. After the commotion extended into the parking lot, Jabbar’s group jumped into the fray to assist Thompson’s and the two wound up side by side.

Jabbar was still only 13. Thompson was a year older, and his group was a Milwaukee branch of the notorious Chicago street gang the Vice Lords, but only in name. Cousins from Chicago had initiated him, and he had in turn initiated some friends.

The kids’ exploits caught the attention of the police and a few months later, Jabbar and Thompson found themselves together again in police custody. Jabbar had beaten up another teen and stolen his jacket. Thompson had swiped his older brother’s gun and used it to steal a bike that belonged to an off-duty cop. They were both sent to the Ethan Allen School for Boys, a juvenile detention facility housed in an old tuberculosis sanatorium 30 miles outside Milwaukee.

The turn against rehabilitation

Democrat Pat Lucey was elected governor of Wisconsin in 1970 as a reformer. He wanted to revamp the state’s criminal justice system, and he directed the Council on Criminal Justice to generate a number of reports reimagining its future.

A committee on offender rehabilitation, which included prison inmates, parolees, and criminologists, produced a final report that identified as its “most fundamental priority” the closure of all Wisconsin prisons by June 30, 1975. It recommended replacing most prisons with locally controlled, community-based treatment programs, supplemented by a small number of new correctional institutions where the few people who posed an imminent risk to the public could receive individualized treatment. As the committee explained:

[N]o amount of resources, however great, can enhance a convicted citizen’s chances for productive re-entry to a democratic society when that citizen has been confined in an institution too large to provide individual services, too geographically remote to provide vital life-contacts, and too regimented to [foster] selt-esteem.

Interest groups like prison guard and police unions squashed the recommendations, but they nonetheless reflected the central objective of the criminal justice system in Wisconsin around the time Jabbar and Thompson were born: rehabilitation.

By the time they were teens, though, this objective was out of vogue. The rate of violent crime in Wisconsin increased more than six-fold between 1962 and 1980. Policy makers and many in the public interpreted the rise as evidence of a failed approach to criminal justice, rather than a more complicated explanation that likely included the aging of baby boomers into their crime-committing years and insufficient government support for the poor.

When Jabbar and Thompson were arrested in 1984, not only had the political appetite for rehabilitation waned, but the surge in crime had hurt the state’s capacity to help incarcerated people reform. As Marquette University law professor Michael O’Hear pointed out in his book, “Wisconsin Sentencing in the Tough-on-Crime Era,” the surge in violent crime overburdened the state’s corrections system, pushing the prison population far past capacity and probation caseloads to ratios greater than 70:1. “Such numbers,” O’Hear writes, “help explain why recidivism rates were high — more than 50 percent, for instance, for male juveniles.”

‘You really have to play the part’

The Ethan Allen School for Boys — where Jabbar and Thompson were first sent — confined children ages 12 to 18 with a smattering of older occupants serving sentences into their 20’s. Detainees had committed robbery, sexual assault, murder, and a litany of other crimes that marked them as too dangerous to live in their communities. When Jabbar, barely a teenager, arrived in the spring of 1984, he didn’t see how he belonged. His first conversations with classmates left him feeling like an amateur among hardened criminals. Thompson, who had arrived roughly a month earlier, felt only slightly more comfortable; the older students reminded him of his brothers.

Being so young, Jabbar and Thompson gravitated toward one another. They bonded over sports (Thompson earned his nickname, “Bear,” in part because of his ability to maul quarterbacks on the football field) and over Jabbar’s collection of college starter jackets, which Jabbar’s mother sent with him so he would look presentable.

Daily life at the facility resembled regular schooling, only in an overcrowded boarding school surrounded by razor wire, and with additional requirements intended to help the boys reform. Residents attended class, participated in therapy, and worked on-campus jobs. If they wanted, they could take vocational classes to learn trades like welding. The school’s superintendent told a reporter in 1996 that residents of Ethan Allen — unlike prisoners in the adult system — were not there “to pay a price,” but rather to learn from their mistakes, and return to society with the tools to live crime-free. “We’re trying to raise kids,” she explained. “We believe that people can change.”

But Jabbar and Thompson mostly remembered being introduced to older teens who knew more about the city’s criminal underbelly, and who proved eager mentors.

Even if the school had helped students change their habits, it had no sway over the conditions beyond its fences. Nor did juvenile detention in Wisconsin in the 1980s require follow-ups with corrections officials or social workers post-release, or participation in any sort of reintegration program to help supposedly rehabilitated children transition back into their communities. When Jabbar’s mother picked him up, after more than six months away, he returned to an environment that was virtually unchanged.

At home, Jabbar reconnected with boys he met at Ethan Allen, now aware of more serious schemes to participate in. When a friend’s father offered him a pack of cocaine to sell, he agreed. Still in high school, he began skipping classes. Jabbar was expelled so many times that his mother had trouble recalling how many high schools he attended.

Smith became Jabbar’s primary mooring to a safer life during this time. The pair met over the phone when Jabbar was at Ethan Allen, connected by a cousin of Jabbar’s who wanted to set them up. But a few months after Jabbar’s release, in December of 1984, the same cousin brought them together in person, at a yellow house in northwest Milwaukee. Jabbar said he knew she was “the one” from their first interaction. Smith was struck by how kind and quiet he was — shocked that someone so gentle, so much like her father, had needed to be locked away with armed guards.

Smith was loud, talkative, and fiery. Friends joked they were “Deserving” of one another — a play on the names Desi and Earvin. Eventually, Jabbar’s parents enrolled him in the same high school, and though he rarely attended, he would take the bus there every day and wait for her at the building’s front entrance. He’d return before the final bell to escort her home.

Jabbar spent increasing amounts of time with his 2-4 friends — drinking, smoking, and plotting their next pay day. As the crack epidemic took root in Milwaukee, he had grown increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of selling drugs, in part because he had begun using periodically himself, and was frightened by the grip addiction had on his life. He had less compunction about robbing drug houses.

Jabbar dropped out of school in 1986. He had a child with Smith, and then another with another girl. The children made Jabbar think seriously about how to extricate himself from his many hustles, but at some point his reputation for violence had become a shield. “You really have to play the part,” he said, “because not playing the part can be the difference between life and death.”

Smith understood this dynamic, but also saw that its most likely conclusions were prison or death. Neither were places for the father of her son. When she heard about Job Corps, a federal program providing free education and vocational training, she decided it was the perfect opportunity. Enrolling at the center in Cleveland would get them out of Milwaukee and give Jabbar space to remake himself. After some persuading, Jabbar agreed.

The pair was accepted to the program in early 1988; their classes would begin in March. Smith bought bus tickets, and arranged housing. Then, in January, in what he envisioned would be a last escapade, Jabbar attempted to rob a drug house. One of the teenagers inside left the home and made it halfway to his car before Jabbar approached with his gun drawn. The teen reached for his own weapon, but Jabbar was quicker — he shot the teen dead. A week later, detectives arrested Jabbar and charged him with murder. A judge sentenced him to 15 years in state prison.

On the outside

After returning from Ethan Allen, Thompson had also begun selling drugs. A barber who had volunteered to cut hair at the facility offered him a job sweeping up around his shop. During his first week, Thompson noticed clients frequently walked straight past the barber chairs into the backroom, then left a short while later without a haircut. When he worked up the courage to ask his boss what was going on, his boss pulled out a toolbox kept in a rusting curio cabinet in the backroom. It held a brick of cocaine. He asked Thompson if he wanted to sell.

Thompson made thousands of dollars a month — enough to buy new clothes and nice chains, and also give money to his mother, who was supporting the family as a certified nursing assistant. When she confronted Thompson about the sudden influx of cash, he told her he got a job at McDonald’s. When she found his money and hid it, he pretended like nothing was wrong. “To me, in my mind, what I was doing was helping, because she wasn’t missing any payments on no bills,” he said.

What began as a path to a more comfortable lifestyle turned into an end in itself. Thompson found himself craving the thrill of a carjacking or an armed robbery. Sometimes, he would rob when he didn’t need the money. Once, he and some friends beat up the man responsible for restocking the vending machines at their school, stealing loose change and a couple bottles of Coca-Cola.

Unlike Jabbar, Thompson performed decently in high school. But home felt like a different world. His white teachers wouldn’t understand his circumstances if he tried to describe them, he thought, so he kept to himself.

Nonetheless, Thompson was proud that Milwaukee was home to a university as beautiful and esteemed as Marquette, with its majestic gothic spires. He drove through campus so often that he memorized each building’s function like a tour guide: Heading west, the school of communications came first, then the libraries, then the schools of engineering and dentistry. He liked to imagine himself on campus, carefree like his white classmates, unconcerned with the prospect of death. He considered applying, but he was sure his felony from the armed bike robbery would get in his way. And if he couldn’t go to college there’s no way he’d be able to get a job. So he turned to the streets full time. Two years after Jabbar’s arrest, in late 1991, police arrested Thompson in connection with an armed robbery of a Domino’s Pizza, and a judge sentenced him to 12 years in state prison.

Tougher on crime

By 1995, Wisconsin’s violent crime rate was 50 percent higher than it had been in 1984, when Jabbar and Thompson went to Ethan Allen. Between 1979 and 1991, Wisconsin’s prison population doubled. In the next six years, it doubled again. This mirrored national trends, and fueled a political preoccupation with being tough on crime. During his 1994 reelection campaign for governor, Republican Tommy Thompson signed the state’s three-strikes law, along with other punitive measures. In a campaign ad, he pummeled a punching bag while talking about crime. He won in a landslide, with 67 percent of the vote.

The following year, Democratic Attorney General Jim Doyle, who was eyeing the Governor’s Mansion, announced support for a hard-line criminal justice policy that had swelled in popularity called truth-in-sentencing. He released a Wisconsin-specific version in 1996.

Truth-in-sentencing laws operated by the logic that the public ought not to be misled about the amount of time people convicted of crimes would spend behind bars. The bills typically curbed or abolished parole, ensuring that those convicted of crimes served the entirety of their sentences. Most iterations, including Doyle’s, contained stipulations about good-conduct credits, which could earn prisoners some small percentage of their original sentence back.

Governor Thompson did not want to be outflanked, so he released his own plan, which ended good-conduct credits. It eliminated parole for everyone, not just violent offenders. Most dramatically, it increased the maximum sentences allowed under Wisconsin law for nearly all felonies by 50 percent or more. The bill mandated extended periods of community supervision, requiring that offenders adhere for years after their release to a set of arbitrary and sometimes confusing conditions, including avoiding conduct “which is not in the best interest of the public welfare or [their] rehabilitation.” Violators were to be locked up for at least a quarter of the original sentence.

The governor’s legal counsel, Stewart Simonson, said years later that his administration expected the bill would be diluted in Wisconsin’s state Legislature. But it was not. Led in part by a young Scott Walker, the Legislature passed what would become one of the nation’s harshest and least flexible sentencing laws.

In the summer of 1998, the bill reached Thompson’s desk along with another 30-some Republican-sponsored crime bills — including one providing for the chemical castration of sex offenders.

Caged, again

Jail was worse than Ethan Allen. At 18, Jabbar still thought of himself as a kid, but the people he was locked up with were adults. They were more mature, more menacing. Incarceration forced Jabbar into a cold-turkey withdrawal from his heroin use; he spent the first week consumed by fear. He was also ashamed. Not only had he taken another person’s life, but he had sabotaged his future with Smith and their son. Jabbar couldn’t believe he would miss the formative years of his children’s lives — first days of school, basketball games, first dances.

Jabbar knew what happened to people who showed weakness in prison. He fought frequently to earn the respect of fellow inmates and whatever protection it would afford. Within his first three weeks at Green Bay Correctional Institution, a maximum-security prison, he nearly received another homicide charge for stabbing an inmate in the eye with a fork. He spent roughly two of his first three years in solitary confinement.

At the time of his second arrest, Jabbar had struggled with reading and could hardly spell. The prison offered high school equivalency courses and, determined not to let Smith down, Jabbar enrolled. He threw his energy into school, and in addition to history and basic algebra, Jabbar learned that he enjoyed reading: Whenever he spoke with his mom, he asked her to send him books — usually about history or self-improvement.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

He and Thompson wrote each other frequently. When the state reduced Thompson’s security classification midway through his second year, he requested a transfer to Jabbar’s facility. The prison approved. When Thompson arrived at Oshkosh, the pair bonded again, trading stories from their time apart. They played basketball and competed in extended games of chess. Thompson had converted to Islam while in maximum security, and he nudged Jabbar to get involved. A few months later, Jabbar converted, and he chose a new name. Hamid Abd-Al-Jabbar roughly translates to “the one who praises and serves Allah” — a fitting description, he thought, to take into his life outside.

In 1994, the state cleared Jabbar for release to a halfway house in Milwaukee, where he worked on a reintegration plan. His family was overjoyed — particularly his youngest sister, Joan. She had turned prison visits into a series of intimate interviews with her brother, who had been absent most of her youth.

Shortly after his arrival at the halfway house, though, Jabbar had a scuffle with a corrections official. He walked out the facility’s front entrance and went home. For 30 days he lived free, and linked up with old friends. When police found him during a raid on a drug house, a judge tacked five additional years onto his sentence, to be served immediately following the end of his original sentence for murder.

Reentry

Jabbar would not return home until 2002, and when he did his parents coordinated a massive reunion party in their backyard. Cousins and uncles drove in from Arkansas. The family got matching T-shirts. They barbecued. The whole affair overwhelmed Jabbar, who didn’t like to be the center of attention.

While Jabbar was away, the internet had exploded and cell phones had morphed from clunky antennaed bricks to Blackberries. The prison had not familiarized inmates with this new technology — Jabbar felt like a time-traveler. He was supposed to be actively seeking work, but with a homicide on his record and no knowledge of the internet, his prospects were limited.

Jabbar’s stepfather was able to get him a job at the tannery, but it paid poorly. Jabbar fell in with old friends, and to supplement his income he returned to selling — and, eventually, using — heroin. He lasted three months on the outside before undercover police arrested him in a sting. He was sentenced to two and a half years, plus four years of community supervision under Wisconsin’s new truth-in-sentencing law.

According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics study that tracked inmates released in 2005, only some 23 percent of freed prisoners manage to avoid rearrest within five years. Among Black offenders, 18 percent.

Jabbar’s family remained confident that he would defy these statistics. But the setbacks were frustrating. Smith felt stung by his absence. At low moments, his sisters speculated that he wanted to be incarcerated. Joan never went so far: “That’s ignorant and dumb for you to say,” she would snap.

Smith, meanwhile, enrolled in college to study criminal justice, then found a high school teaching job. Jabbar admired her desire to give back. The synopsis of his life showed a man who had only ever taken or destroyed, and he wanted to help for a change. Smith asked him to write letters to her students from prison, telling his story so they might learn from his mistakes.

After he was released in late 2006, he found sporadic work detailing cars. He spent more time with his sons, deepening their relationships. Smith started a master’s program in mental health and substance abuse counseling.

Yet, despite all this good fortune, Jabbar felt uneasy. He had lived most of the past 20 years under the impression that his absence had held his loved ones back — Smith, in particular. Now he found she had thrived without him — in fact, his scant pay made him the dependent one.

As his four years of community supervision drew to a close, the festering insecurity pushed Jabbar back to drug dealing. Smith didn’t know about the drugs, until he didn’t come home one day in October of 2010. A police officer had tried to pull Jabbar over, and he had fled. Before nearly crashing his green Chevrolet Tahoe into a tree, he tossed a baggie filled with heroin out his window, and a nearby witness turned it over to police. He was sentenced to six years in prison, plus seven years community supervision.

414LIFE

Following a historic 70 percent surge in homicides and nonfatal shootings in Milwaukee in 2015, Mayor Tom Barrett sought to expand the focus of the city’s Office of Violence Prevention. Until that point, the office had concentrated on domestic violence and illegal gun access; it would now work to combat neighborhood street violence.

To helm the reoriented agency, Barrett tapped Reggie Moore, a local activist who had run successful youth programs in the city since the early aughts. Moore insisted that the community dictate the priorities of the office, and an engagement process showed that residents wanted a violence outreach program. Moore and his team researched effective models across the country, and put together a program called 414LIFE, which would send locals who had served time into the streets to mediate conflicts without the police.

Moore wanted to find local partners to help organize 414LIFE, and wound up collaborating with a social services agency Smith was involved with. When she heard about the program, she saw it as the answer to Jabbar’s growing desire to apply his life experience toward some altruistic end. She waited, buzzing with excitement, for Jabbar’s next call.

Jabbar returned home just weeks before the board began interviewing candidates for the program’s outreach worker positions, and the two rehearsed exhaustively for an interview Smith arranged. “Don’t be stiff,” she’d tell him. “Just tell your story. Your story is your strength.” When she took Jabbar before the board, she brought along two other candidates to disguise their connection. She didn’t want Jabbar to get the job simply because they had plans to marry.

In August of 2018, 414LIFE offered Jabbar a part-time position.

A fragile reunion

When Thompson received Jabbar’s call that December afternoon, after Jabbar’s client threatened to shoot him in the McDonald’s parking lot, he had been out of prison himself for about four years. Like Jabbar, he had struggled to find consistent work — in West Bend, a printing company shot down his application on account of his record; in Madison, a factory making the coatings for time-release pills offered him a job, but rescinded it after a background check. He did a second turn in state prison for theft, then another in federal prison for a string of bank robberies.

Following his latest release, he moved to a halfway house in Janesville, Wisconsin, and found work driving a forklift at the power company. He met a woman on Craigslist, and they dated. He loved her photography; they finished each other’s sentences. He proposed.

The pair moved to Wausau, Wisconsin, and started a cleaning company. For four years, the longest period he had spent free since his teens, Thompson made his money flyering college campuses with offers to deep-clean dormitories and study halls. His record still limited him — he remembers the owner of a trailer park refusing to let him and his fiance purchase a mobile home because of his background — but he managed the period free of crime.

Then, in summer of 2018, shortly after Jabbar’s release, Thompson’s brother — until then their mother’s sole caretaker — died, forcing him to move back to Milwaukee.

Thompson returned without work or a place to stay. Most of his friends still plied street trades, and he considered joining them to eke out some breathing room. But first he called Jabbar to tell him he was back.

The pair met up at Smith’s house, and Jabbar told Thompson that he and Smith planned to marry. He said he was excited about a possible part-time gig with 414LIFE. Never before had he imagined that his challenges might enable him to help others. Jabbar said that through 414LIFE, he would be able to offer his clients access to job placement programs and low-income housing. He could help Thompson.

Thompson left that meeting so proud of where his friend’s life was headed. But less than five months later, Jabbar was asking for a gun.

Thompson met up with Jabbar just a few blocks from the McDonald’s, and Jabbar climbed in his passenger seat. He asked Thompson for the pistol, but Thompson held onto it. “Look, you’re doing some positive stuff,” he told Jabbar. “I want you to keep doing what you’re doing.” Jabbar remained quiet. “Tell me who it is, and I’ll take care of it for you.”

Jabbar sat there. Had Thompson just offered to kill a man on his behalf?

He managed a “wow” while the steam in his head settled. “You think that much of me, that you don’t want me to jeopardize myself,” he said, halfway between a question and a realization. He sat with the thought. “If you think that much of me, then I should think the same of you.”

Jabbar’s anger dissipated. He agreed to let the whole thing go.

It was a marker for Jabbar, a sign that he had finally outgrown the impulsivity of his youth. The idea that a person’s choices reflected their sense of self-worth clarified his past run-ins with the law. And it energized his outreach. Within a few months, he earned full-time employment with 414LIFE.

Jabbar helped Thompson land a gig with a local rehabilitation clinic training for a drug abuse counselor certification. He became one of the organization’s most effective and relentless interrupters, out-canvassing many of his colleagues by miles a day. By January of 2021, he had earned a promotion, and was appearing frequently on local news. He was enjoying his longest stretch of freedom in more than a decade.

The work, though fulfilling, was difficult on Jabbar. Every day, he interacted with people suffering the effects of the kind of violence he had participated in decades earlier. In 2019, he began using heroin again. Two years later, on February 11, 2021 he died of an overdose after using heroin laced with fentanyl.

Jabbar’s family scheduled an open-casket funeral in a grand, cavernous church two miles from the neighborhood where he grew up. Inside, Smith forced a shaky smile and busied herself with greetings and logistics. Attendees had been instructed to dress in Adidas — since he was a teen, Jabbar had been obsessed with the brand, and sported their tracksuits like a uniform. He was buried in a cherry-red tracksuit with white stripes.

The mayor issued a proclamation commending Jabbar’s service, which Moore presented to the congregation and left with Smith. His boss at 414LIFE, Derrick Rogers, spoke about Jabbar’s short window of activism, emphasizing that, though two years can seem short, “two can be so full of love, so full of service, so full of compassion… that God confounds it and makes it bigger than any” number of years spent in prison or on the street.

Smith wrote a similar message in the program: “I wish you could hear how the people miss you, see you behold the hero and influence you were to me and so many… I promise I’m going to do my best to live out your passion.”

When the floor opened for remarks, Thompson, sitting four rows back from the pulpit in an off-white Kufi and a gray Adidas jacket, watched in silence. The week leading up to the ceremony, Thompson had mulled over what he might say, but couldn’t settle on anything that adequately captured their friendship, or his grief. Friends, relatives, and coworkers shared funny stories of Jabbar’s youth and moving tributes to his mentorship. In between each speaker, Thompson half-rose, then sat again, uncertain that he had anything valuable to offer.

Eventually, Thompson stood and walked slowly onto the stage, with his right arm tucked behind his back. “He’s gonna be dearly missed,” he said. “But that man went out on the highest note possible.”

On his way out of the church, Thompson — who has since been hired by 414LIFE — seemed to reflect on those final words. He remarked on the number of people who had come out to celebrate someone who had once caused so much harm. “I can only hope that I’d be so lucky.”