Mass shootings have become so frequent in America that we are often left with the feeling that random, indiscriminate gunfire can happen anywhere, without warning. In recent years, gunmen have killed moviegoers at a theater; people at a gay nightclub and a country-western bar; young children in elementary schools; and worshippers at churches, mosques, and synagogues. Last week, the five-year anniversary of the country’s deadliest antisemitic shooting, in Pittsburgh, coincided with the manhunt for a shooter who allegedly killed at least 18 people, wounding more than a dozen others, in a series of attacks across Lewiston, Maine. In 2021, the U.S. had 690 shootings with four or more victims. Last year had the second-highest count, at 645. So far this year, the United States has endured 565 mass shootings in 298 days.

It’s easy to recall some of the tragedies that have branded cities and towns with a uniquely American infamy: Parkland, Uvalde, Newtown, Sutherland Springs, El Paso, Aurora. But the shootings that dominate national attention for days or weeks are only a fraction of the high-fatality shootings occurring nearly every day in America — in Macomb, Illinois and Hialeah, Florida; Pine Bluff, Arkansas and High Point, North Carolina, where in January a man killed his wife, three children, and then himself.

This can lead to misperceptions about how these tragic events fit into America’s larger gun violence crisis, and how people and political leaders respond to it. Here is an overview of the most important things to know about mass shootings:

Have shootings like those in Uvalde and Lewiston become more common?

Short answer: yes.

To take a historical view, let’s look at data from The Violence Project, a nonprofit that studies what they call “public mass killings,” in which four or more people were killed in a public space. They also filter out shootings that are domestic in nature, and those that are part of ‘ordinary’ crimes, like armed robberies, or gang activity.

This data goes back to 1966, which is when the University of Texas tower shooting occurred. That incident is considered by some experts to be the first public mass killing.

Public mass killings 1966 – 2023

The Violence Project tracks shootings in which four or more people were killed in a public space. They do not include domestic shootings or those that occurred in the context of criminal activity. These shootings have become both more deadly and more frequent over time.

Judging by the number of instances, public mass killings have increased each decade, reaching more than five incidents per year in the 2010s. In the 2020s, the rate so far is more than six incidents per year, putting this decade on track to have the highest rate of mass killings yet.

If we judge the scope of these killings by the number of people killed, it peaked in the 2010s, with more than 50 fatalities per year. So far, in the 2020s, the rate is just over 40 deaths per year, although some of this decrease is likely explained by the near-absence of such killings during the height of the pandemic.

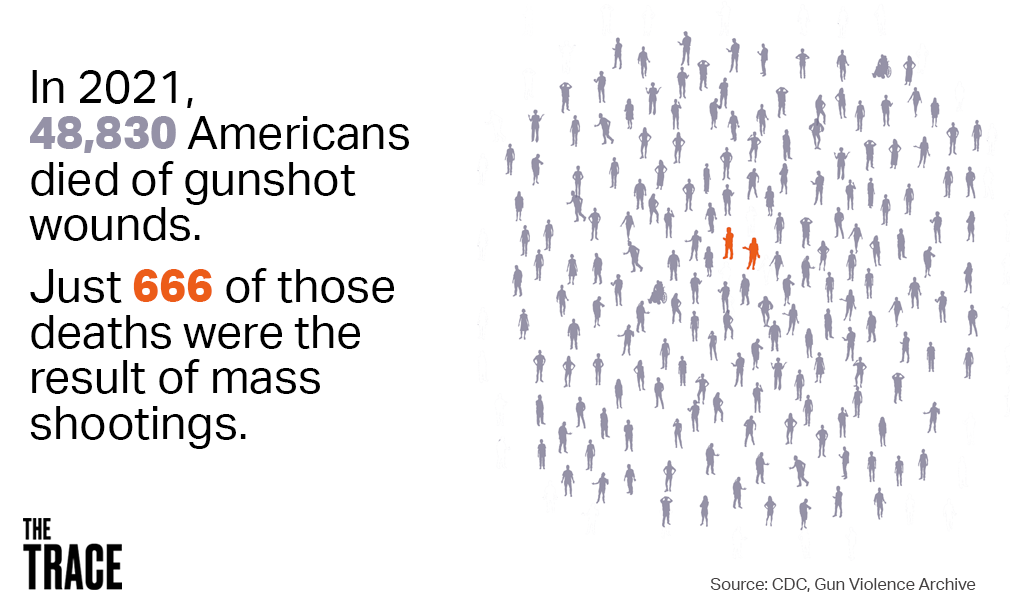

Mass shootings make up a small portion of all U.S. gun homicides.

Suicides have long accounted for the majority of U.S. gun deaths. In 2021, the most recent year for which complete federal data is available, 54 percent of all gun-related deaths in the U.S. were suicides (26,328), while 43 percent were homicides (20,958). The remaining gun deaths that year were accidental (549), involved law enforcement (537), or had undetermined circumstances (458).

Most mass shooting victims are Black.

Traditionally, researchers have used a restrictive definition of a mass shooting as an event in which four or more people, excluding the perpetrator, are shot in a public place, and the act was not committed as part of a crime for profit or with the goal of terrorism.

The problem is, using that definition ignores many Black victims, who die from gun violence at nearly 2.4 times the rate of white Americans, according to federal data.

If we use the definition advanced by Gun Violence Archive, of a mass shooting of four or more people shot at one time, excluding the perpetrator, regardless of how many people are killed, we capture a broader phenomenon. And we see that nearly 50 percent of 2020 mass shootings analyzed by The Trace took place in majority-Black census tracts, though less than 10 percent of census tracts nationally have majority-Black populations.

Gun violence isn’t just an urban problem.

Even as data shows otherwise, the perception that urban communities are the epicenters of America’s gun violence crisis persists. In reality, rural communities have the highest rates of gun ownership in the country, and between 2011 and 2021, the overall firearm death rate in rural counties was nearly 40 percent higher than in urban counterparts. This pattern extends to homicides: In 2022, the Center for American Progress published a report that found that, when you account for population size, rural communities had higher rates of gun homicide than urban communities.

“I think it is important that we combat the narrative that this is a city problem,” researcher Nick Wilson told The Trace.

The majority of mass shooters obtain their weapons legally.

The 18-year-old gunmen who terrorized Buffalo and Uvalde bought their weapons legally. The gunman who killed 49 people at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando purchased the rifle and handgun he used from a federally licensed firearms dealer. The gunman behind the San Bernardino massacre purchased two of the handguns used from a California gun shop. An analysis of large-scale mass shootings by The New York Times found that 13 out of 16 shooters purchased their guns in a similar fashion — legally, after undergoing a background check administered by a federally licensed dealer.

Mass shooters often fit a psychological and behavioral profile.

Many of America’s most notorious mass shooters have been young, angry men who displayed antisocial behavior before they carried out attacks. A team at the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions analyzed 110 gun homicides of four or more people between 2014 and 2019 and found that in 68 percent of events, the perpetrator either killed an intimate partner or a family member, or had a history of domestic violence.

In 2015, a University of Alabama researcher found that a uniquely American cultural and mental strain leads mass shooters to target workplaces and schools — as opposed to the military installations often targeted in other countries — because these institutions represent the societal forces that gunmen believe have mistreated them.

Children are more likely to be shot at home than at school.

While more than two-thirds of parents worry a shooting could happen at their children’s school, our reporting found that home is a far more dangerous place for kids. From 2018 through 2022, at least 866 kids ages 17 and younger were shot in domestic violence situations, according to an analysis by The Trace of data from the Gun Violence Archive. At least 621 died. In that same timeframe, 268 children were shot at school, 75 of them fatally, according to an analysis of data by a federally funded tracker — launched after the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida — and the Gun Violence Archive.

The median age of the child domestic violence shooting victims over the five-year period was 10; 167 of the victims were younger than 5.

Are mass shootings contagious?

Not exactly, The Trace’s Chip Brownlee found when he explored this reader question.

An increase in mass shootings, especially high-profile public mass shootings, doesn’t necessarily mean that the contagion effect itself is getting stronger, but that there is a higher baseline of shootings — determined by a number of factors, including economic conditions, changes to gun laws, or the number of guns in circulation. More mass shootings overall means more people are exposed to them, mimicking a ‘contagion,’ but these singular events are not necessarily motivating potential perpetrators, or being copied by them.

Media coverage of mental illness exaggerates its role in gun violence.

According to a 2021 study by researchers at Columbia University, severe mental illness, like active psychosis, is a factor in only about 5 percent of mass shootings worldwide. While the perpetrators who were studied did have diagnoses like substance abuse and depression about 25 percent of the time, the researchers found those conditions to be “incidental” in most cases.

Focusing on a shooter’s mental illness can also add insult to the injury experienced by the bereaved. In Buffalo, for example, Black community members and mental health providers felt the national narrative that followed the 2022 killing of 10 people at a supermarket did more harm than good: It centered the gunman’s mental health and online engagement with hateful ideologies instead of the historic and lasting trauma of his attack on one of the most segregated neighborhoods in the country.

It’s rare for a “good guy with a gun” to intervene during an active shooting.

Gun rights activists say they want to abolish so-called gun-free zones — areas where guns are not permitted, including schools and many private businesses — because they deny civilians who would otherwise be carrying firearms the opportunity to stop a massacre, providing an unprotected target for mass shooters looking to perpetrate large-scale carnage. Indeed, the frequent claim of the National Rifle Association is that more “good guys” carrying guns in public will make society safer. There is no evidence to support this claim. Of the 160 active-shooting incidents from 2000 to 2013 analyzed by the FBI in 2014, only one active shooting was stopped by someone with a valid firearms permit. Twenty-one were stopped by unarmed bystanders.