Marc Mendiola was tired of seeing his high school classmates in crisis, especially knowing that so many of them lived in households with guns.

During his freshman year, he noticed that some of his friends experienced depression and suicidal ideation so intense that some days, they didn’t seem like themselves at all. The light behind their eyes was gone. Sometimes, they went to the counselor at their South San Antonio, Texas, high school to share how they were feeling, and the counselor would send them away with a list of therapists they could contact outside the school. But few of those therapists took Medicaid. Or spoke Spanish. Or stayed open past 5 o’clock.

“We don’t have the resources to get help,” Mendiola said. “All we have easy access to is guns, to take the easy way out.”

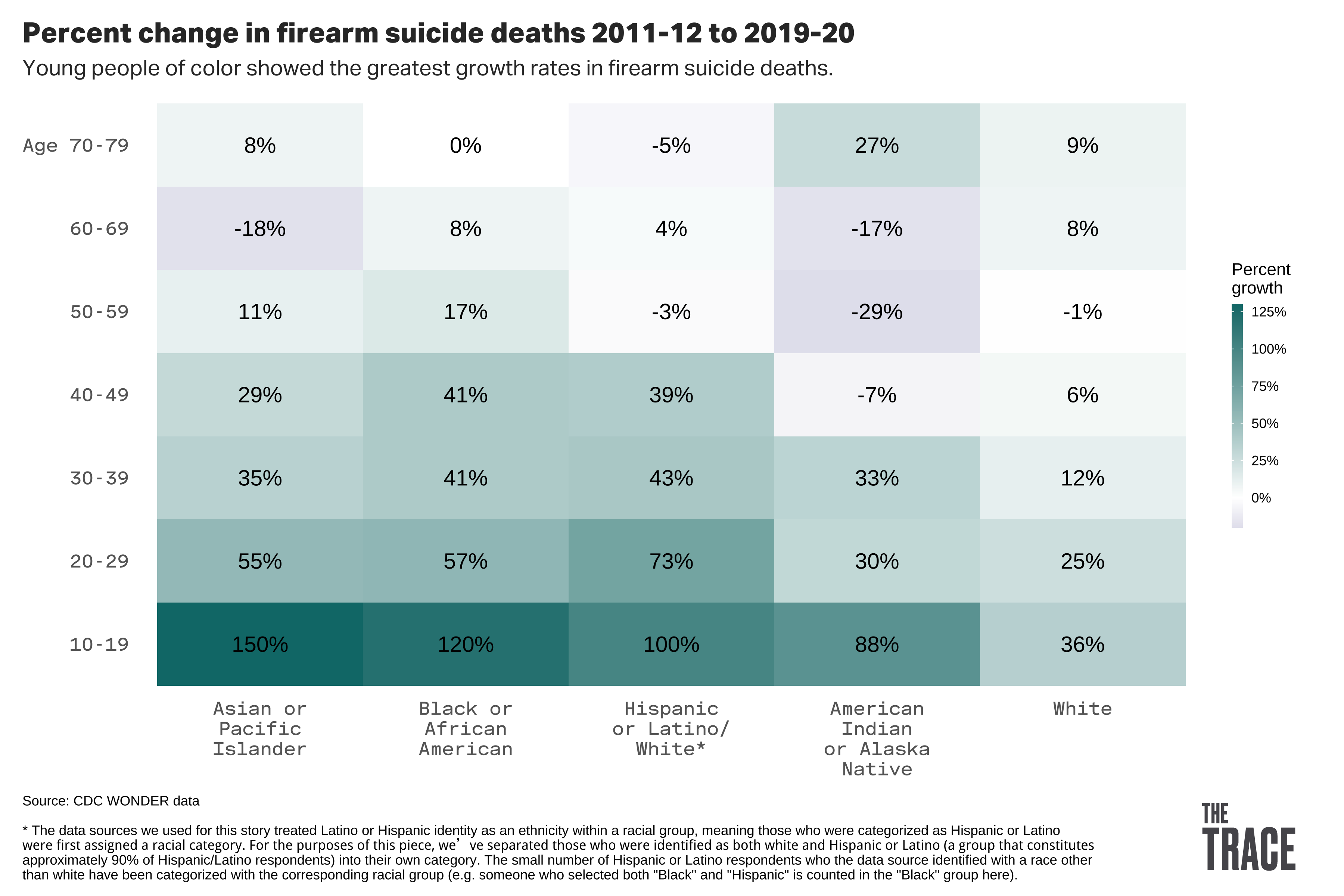

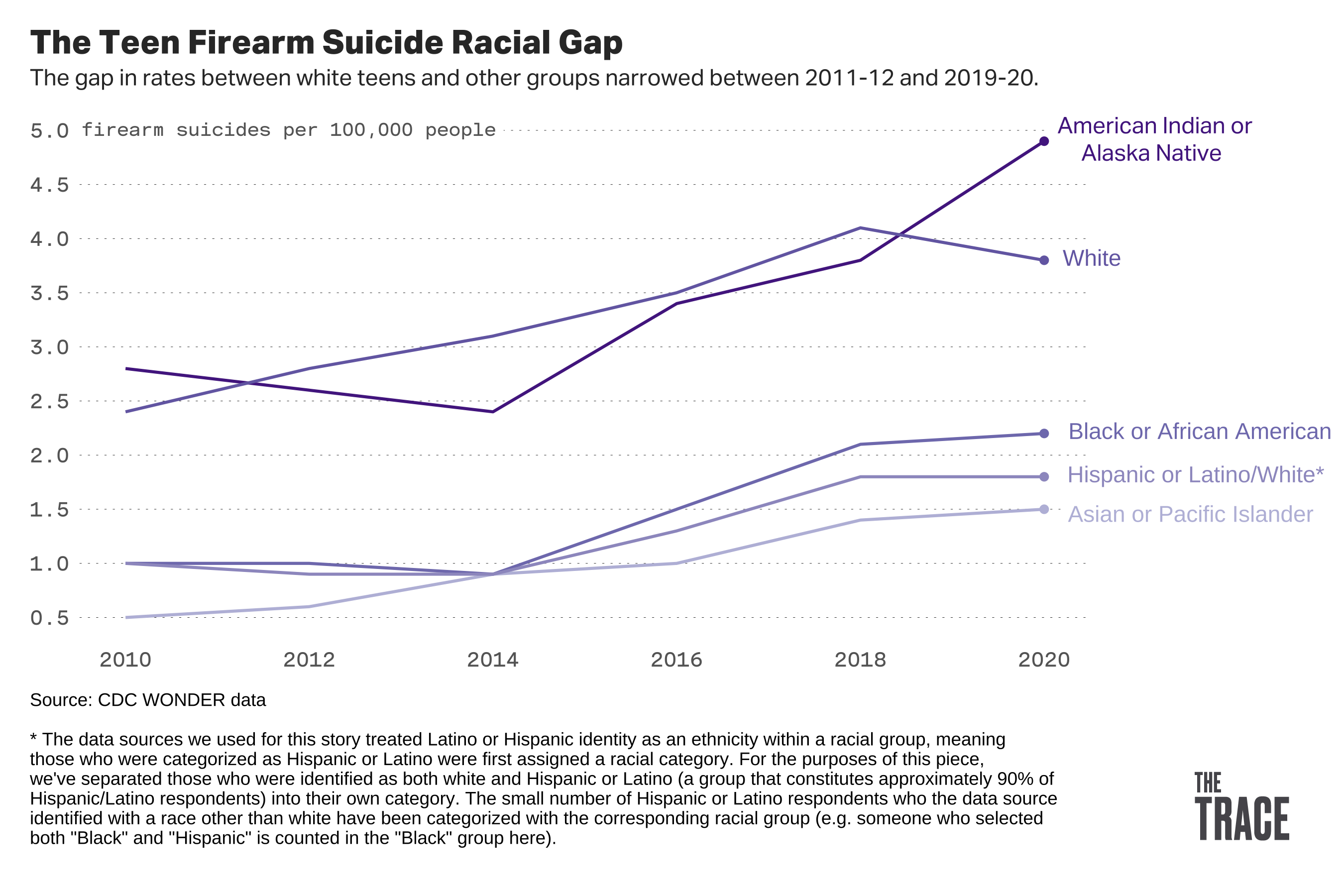

Mendiola is part of a demographic that’s increasingly vulnerable to gun suicide. An analysis of public health data by The Trace reveals that firearm suicide rates rose steadily among young people in their teens and twenties over the last decade, with the sharpest increases among people of color.

The firearm suicide rate more than doubled among Black, Latino, and Asian teenagers, while it increased by 88 percent for Native Americans and 35 percent for white teens.

From 2019 through 2020, an American teenager took their life with a gun every seven hours on average.

Historically, victims of gun suicide have tended to be white, male, older, and live in rural areas. The single highest gun suicide rate for any group in our analysis was among white people in their 70s, followed by white people in their 50s. Rates among these older, white groups remained relatively stable across the 10-year period we analyzed, a stark contrast from the rates in younger people and people of color even as the latter groups made up a much smaller portion of overall deaths.

The Trace analysis is “frightening,” said Theodore Beauchaine, a psychology professor at the University of Notre Dame who specializes in preventing suicide in children. “Suicide rates have always been highest in the older, white group,” he said, “but everyone else is catching up.”

The figures come from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s interactive WONDER database, which derives mortality data from death certificates collected at the state level. For this analysis, we compared the combined suicide rate of 2011 and 2012 to the combined rate of 2019 and 2020.

“There is no single cause to suicide and as such there is no single solution. Factors contributing to suicide exist at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels,” a CDC spokesperson said.

Suicide reduction, they said, “includes reducing access to lethal means such as firearms and medications among people at risk. Safe storage of lethal means has been shown to reduce youth suicide attempts.”

Researchers point to the general increase in youth suicides, the strain that comes with being young and a person of color, as well as disparities in the level and quality of mental health resources available as factors, in addition to changes in patterns of gun ownership.

Firearms are involved in about half of all suicide deaths. A 2021 analysis of childhood suicide data between 2013 and 2017 found that guns were the second most prevalent suicide method used by kids aged 5 to 11, and in nearly every case, they got the gun from their home.

Find Support

Help is Available 24 Hours a Day

Crisis Text Line

Text 741741

The Veterans Crisis Line

988, press 1, or text 838255

Help Someone Else

Understand warning signs.

Dr. Alfiee Breland-Noble, a psychologist and founder of the AAKOMA Project, which aims to bring mental health care to marginalized youth, says the increase in gun sales in recent years brought millions of weapons into homes without ensuring there was corresponding education around the potential dangers. “More people overall have access to guns, but we don’t have the checks and balances that are necessary to ensure that people know what to do with the guns when they get home,” she said. “For some people, safe gun storage is putting it on a high shelf.”

Children of color also encounter unique stressors, including racism on both individual and systemic levels. “Black people particularly have a high risk of early trauma,” says Dr. Rhonda Boyd, a psychologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia who treats children and adolescents. “There are limits to access to wealth in Black communities, and where people can live. It sets up conditions in which a neighborhood’s going to be under-resourced.” The level of gun violence in a community is another contributor to early trauma, she said.

Breland-Noble said the rise in Black and Latino suicide over the last decade coincided with a period that saw several public incidents of police brutality and killings of people of color. These images were played around the clock on cable news and amplified by social media. “Our young people are taking all of that in,” she said, and they may have internalized the message that “no one’s going to care if I’m not here.”

Sean Joe, a national expert on Black suicide and a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, first identified a rising risk of suicide attempts among Black children more than 15 years ago. He said the disinvestment in Black communities, which accelerated in the 1980s, sends a message to children of color that nobody wants to support their development. “They’re making a mental calculation that their death is more valued than their life,” Joe said. “That’s just a tragic thing. When you have that crisis, and you put a gun in that situation, where guns are lethal 80 to 90 percent of the time? It makes a huge difference.”

The steepest rise in gun suicide was seen among Asian and Pacific Islander Americans between the ages of 10 and 19. Dr. Y. Joel Wong, a psychology professor at Indiana University Bloomington, said this is “very disturbing, but not terribly surprising.” He puts it down to the changing demographics of the Asian community in the United States. This group had been insulated from the high gun suicide rates of other demographics, Wong said, in part because the countries that many Asians emigrate from, including China, India, and Korea, “just don’t have a culture of gun ownership.” He speculates that gun suicide rates are rising now because the community, once primarily comprised of people born overseas, now includes a greater proportion of people who were born and raised in America and thus absorbed the country’s gun culture. And more guns, he said, lead to more suicides.

Wong, who has studied suicide in the Asian American community for more than a decade, said that for adolescents with suicidal ideation, problems with family and school are important stressors. “Differences in cultural values between immigrant parents and their children leads to lots of conflicts,” he said. And those children rarely reveal that they’re considering suicide, Wong said, noting that Asian Americans seek mental health treatment for suicide at lower rates than any other group. “We need a lot more interventions for college students and adolescents,” particularly ones that “get family members to better understand each other, to diffuse cultural-related conflicts.”

The researchers we spoke with identified several barriers to mental health care for children and adolescents of color. One of them is the school-to-prison pipeline. Dr. Boyd of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia said that when children of color exhibit symptoms of mental illness at school, it can lead to discipline — or worse, arrest. Black students are much more likely than their white peers to be funneled into the criminal justice system, as opposed to the mental health care system, where they will get the most help.

The child welfare system can be another deterrent to seeking care. Breland-Noble of the AAKOMA Project says that when she worked on a study of Black women with postpartum depression a couple of years ago, some of her subjects were reluctant to talk about their condition “because they were afraid child and family services might be called in to take their children away from them” — another scenario that befalls Black families far more often than white families.

Yet another barrier to mental health support in communities of color is a lack of providers of color. Only three percent of practicing psychologists are Black, 4 percent are Asian, and 7 percent are Latino, according to the American Psychological Foundation. Many white health care providers are ill-equipped to engage with patients about issues unique to the Black community. “I actually had someone email me this morning seeking care, a person of color, because the provider they had prior was uncomfortable talking about race with them,” Breland-Noble said. “We don’t have enough culturally competent providers. And it’s not a racial match that’s required — it’s an empathy and a training match.” Black people are less likely to trust the health care system because their concerns are often minimized or disregarded by doctors. And patients of color who leave therapy often don’t return, Breland-Noble said.

We don’t have enough culturally competent providers. And it’s not a racial match that’s required — it’s an empathy and a training match.

Dr. Alfiee Breland-Noble

Beauchaine’s research at Notre Dame focuses on primary prevention — intervening before a first suicide attempt — which is especially important with firearms because second chances to intervene are so rare. “To identify kids who are at super-high risk we’re having to go younger and younger,” he said, preferably before age 10.

His team is starting a suicide prevention program for children in South Bend, Indiana, the community that surrounds the university. But reaching kids in the most under-resourced public schools has been a challenge. “Those schools are understaffed, and what staff there are, are underqualified, and that has to result in disparities,” Beauchaine said.

The South Bend project will target two at-risk groups he called “very underserved”: low-income Black and rural communities. But best practices for dealing with families with young children in these demographics are scarce. “We’re inventing things as we go.”

Psychiatrist Amy Barnhorst is the director of the BulletPoints Project at the University of California, Davis, which strives to educate health care workers to be “culturally humble” when it comes to dealing with marginalized groups and firearms, and to provide “culturally appropriate messaging around mental health crises.”

“If you live in a place where you don’t feel safe, don’t feel like the police will help you, and you know other people have guns, it’s hard to persuade you you don’t need a gun,” she said.

But Barnhorst said that doesn’t mean health care providers can’t ask important questions, such as whether a suicidal patient has a firearm in the house. They can also share resources about safe firearm storage. At the very least, they can encourage patients to let a trusted person “babysit” their firearm if they are in crisis.

“We talk about water heaters and smoking, but firearms should be a part of that,” she said.

Barnhorst’s project is supported by a state grant instituted by lawmakers who cited a lack of federal funding for gun violence research. The project receives requests from across the country for resources and workshops, especially because many doctors don’t feel like they were taught about discussions around firearms in medical school. It is not always able to keep up with the tremendous demand, Barnhorst said.

“A lot of physicians feel helpless, but they’re not helpless,” he added.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

One of the biggest barriers to care, according to researchers who study Black youth suicide, is the stigma associated with seeing a psychiatrist with many Black communities. “There’s this idea that you’re gonna be labeled as crazy,” Breland-Noble said. “And particularly in communities of color, no one wants that label. Because you already have enough struggles being Black, so you do not want additional labels added to it to marginalize you even further.”

Complicating the search for solutions is the fact that studies by and about Black people have been historically underfunded. Dr. Breland-Noble says that when she started out 20 years ago, “I was told that Black children’s mental health, and their issues around suicide, are no different than white kids’, so why do these kids need a different type of attention? It’s been such a struggle to get people to understand that this is an issue.”

And when Black people are the subjects of studies, they’re often studied as a monolith, with little regard given to variations in socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, education level, or country of origin, the researchers said. In the most egregious cases, study subjects are grouped into two categories: white and nonwhite. “Nonwhite is not a racial category,” Breland-Noble said.

Wong of Indiana University Bloomington said the research on Asian-American suicide is, in a word, “dismal.” “It’s kind of a forgotten minority,” he said. “Sometimes it’s tied to the model minority myth: ‘They do so well, rates of suicide aren’t that high compared to other groups, so therefore it’s fine.’”

Ultimately, Mendiola and his classmates in San Antonio realized that if they wanted therapy, they were going to have to get it themselves. So they waged a public campaign to expand mental health services at their school. After two years of lobbying school officials and local lawmakers, a group of nonprofit organizations opened a mental health wellness center in the district. Last July, the county board of commissioners pledged $4.75 million to expand the effort.

Now 21 and an architecture major at Texas A&M University, Mendiola marvels at what he and his classmates accomplished. But, he says, it shouldn’t be this hard to get therapy, “We have a lot of walls, and they keep being built in front of us.”