What do you want to know about guns or gun violence? Ask The Trace is a project driven by the curiosity of readers like you. You can read all the articles in the series here, and submit your own questions here.

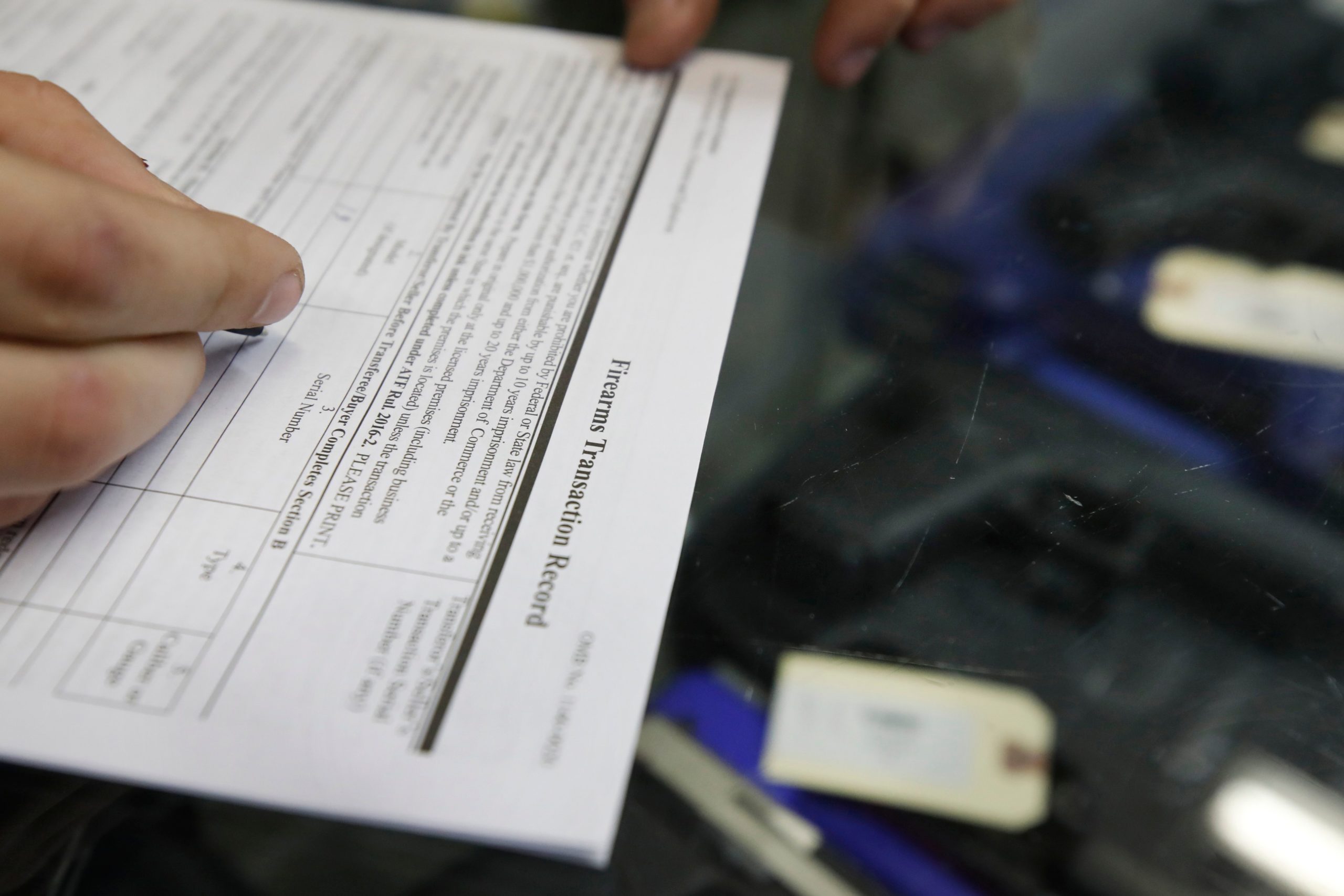

People don’t generally want to be blocked from buying a gun by the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, or NICS. Every year, the federal system stops tens of thousands of felons, people with misdemeanor domestic violence convictions, unlawful users of controlled substances, fugitives who’ve fled the state, and others from buying a firearm.

That’s why we were so intrigued by a question that we received recently from a reader:

How do you get a mentally ill relative’s name added to the NICS database to prevent a gun purchase, if they voluntarily request to be added? My significant other experiences suicidal ideations. The idea that they can legally buy a firearm is troubling to them and they have expressed an overwhelming temptation to do so. They have no history of violence or self-harm, or harm to others, but who knows if the ideations will turn into plans?

The short answer: In most of the country, it’s not possible to voluntarily add oneself to the federal background check system. To be blocked from buying a gun on the basis of mental health, an individual must be adjudicated mentally unfit by a judge or involuntarily committed to a mental health institution. However, residents of certain states have other options.

Find Support

Help is Available 24 Hours a Day

Crisis Text Line

Text 741741

The Veterans Crisis Line

988, press 1, or text 838255

Help Someone Else

Understand warning signs.

In Utah, Virginia, and Washington state, people in crisis can add themselves to a so-called “do not sell” list, which prevents them from buying firearms for a period of months or years. The concept is similar to “no gambling” lists that allow people with gambling disorders to ban themselves from casinos. The policy was first applied to guns in 2013 by Fredrick Vars, a University of Alabama law professor who has bipolar disorder.

“I have been suicidal at points in my life, and the idea of taking away access to most legal means is really appealing to me personally,” Vars told The Trace. While researching the topic, he found a strong association between restricting access to guns and a reduction in suicide. He surveyed people with psychiatric conditions, asking them if they’d sign up for a voluntary, temporary gun-buying ban, and nearly half said yes. Vars teamed up with his mentor, Yale law professor Ian Ayres, and the pair started developing model legislation to share with lawmakers across the country.

With “do not sell” lists, a person can submit their name to law enforcement officials, who enter it into NICS and state databases. The person would remain a prohibited purchaser for a certain period of time — in Washington, it’s a minimum of seven days, while in Utah, it’s at least 180 days. If the person were to try to buy a gun within that period, they would be denied. If the person wants to be removed from the list before that time period is up, they’re subject to a waiting period, whether it’s a week (Washington state), three weeks (Virginia), or a month (Utah).

Guns are a particularly lethal means of suicide: They are fatal in 82 percent of suicide attempts. Research shows that other methods are far less likely to be fatal, and survivors are far less likely to initiate another attempt, according to Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“You see a real reduction in total suicide just by cutting off access to guns,” Vars said.

“Do not sell” lists were implemented in Washington state in 2019, Virginia in 2020, and Utah just this past May, all with bipartisan support. Vars says he’s trying to persuade lawmakers in other states to take up bills. The lawmakers who are most receptive to such legislation, he says, have lost a family member to suicide. A national bill is a steeper climb because of partisan gridlock on Capitol Hill, Vars says. “My hope would definitely be that we get a federal law,” he said. “Because it is a missing tool in suicide prevention in 47 states.”

While “do not sell” lists prevent someone from buying guns at some point in the future, they don’t address guns people already own. In 19 states, police officers and sometimes family members and employers can invoke a red flag law to temporarily disarm someone deemed a risk to themselves or others. But a judge ultimately determines whether a gun owner can keep their firearm; people can’t invoke a red flag law to disarm themselves.

An informal alternative to “do not sell” lists is voluntary gun storage, whereby people in crisis temporarily surrender their firearms to participating gun shops and law enforcement agencies. In 2019, physicians at the University of Colorado teamed up with public health experts and gun rights advocates to create a map of places where people in crisis can temporarily store their guns. Sara Brandspiegel, the Colorado public health official who came up with the idea, told The Trace last year that she drew inspiration from a state government map designed to help people safely dispose of medications. Gun storage maps have since been created in five more states: Maryland, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, and Washington.

Gun shop owners across the country have been providing this service for gun owners in their communities on an informal basis for years. And in Pennsylvania, a nonprofit launched by two firearms instructors, called Hold My Guns, connects gun owners to temporary storage locations in Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Missouri.

Even the gun lobby supports the concept: The National Shooting Sports Foundation, the gun industry’s trade group, recommends the temporary off-site storage of firearms for gun owners in crisis.

“We can’t just throw up our hands and say ‘guns are bad and there’s nothing we can do,’” Dr. Fred Rivara, the University of Washington School of Medicine professor who directed that state’s map project, told us last year. “In fact, there are things we can do while at the same time respecting people’s Second Amendment rights.”