Fredrick Vars remembers the moment when the idea for voluntary gun control came to him. It was the fall of 2013 and he was attending a talk by Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan at the University of Alabama, where he works as a law professor. She was talking about going bird-hunting with Justice Antonin Scalia. Vars, who’d been writing about mental health and gun issues in the context of law, has dealt with depression since he was a teenager. He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at the age of 31 and at times has contemplated suicide.

His idea was this: People who’ve experienced periods of depression and suicidal thinking should be able to remove guns from the equation. Why not create a system for them to suspend their own ability to purchase a firearm until they feel better? Given his own experience with mental illness, he wished it was something he could do at that very moment.

“I instantly believed it would appeal to a lot of people who have mental health problems like mine,” he said. “It doesn’t take anyone’s liberty away from them, it just gives everybody a new type of liberty — the liberty to control gun purchasability.”

Vars shared the idea with his mentor, Yale law professor Ian Ayres, and the pair started developing a policy proposal to share with state lawmakers across the country. They draw parallels to the “no gambling” lists that exist in many states, through which gambling addicts can ban themselves from entering casinos for a period of years, or for life.

This year, Washington became the first state to put a voluntary “do not sell” law into effect. Similar legislation has been introduced in Oregon, Wisconsin, Louisiana, and five other states.

“To me it’s about respecting the autonomy of people even though they may have mental illness,” Vars added. “They’re still independent agents and ought to be able to control their own destiny.”

The bill’s main sponsor in Washington state was Jamie Pedersen, a Democratic senator. “It’s kind of an experiment. Nobody’s done it before,” Pedersen said. “There’s very little downside to making it available to people as an option.” The legislation passed with bipartisan support in March 2018 and took effect January 2019.

The process of banning yourself from guns in Washington state is fairly simple. It starts with a person filling out a short form and presenting it, along with identification, at any county clerk’s office. After verifying the person’s ID, the clerk mails the document to the Washington State Patrol, which has 24 hours to enter it into the federal background check system, as well as the state’s crime database. If that person were to then try to impulsively buy a gun anyway, he or she would be denied.

Residents who waive their firearm rights also have the option to un-waive them — as long as it’s been at least seven days since the waiver was filed and they are not otherwise prohibited from gun ownership. They file another short form and wait for the state police to remove them from the system, which restores their ability to purchase a gun. The clerk and State Patrol must then destroy all records of the person’s initial waiver.

The waivers are designed to be confidential, and can’t be used in legal proceedings nor as a condition of employment or mental health treatment. Senator Pedersen added the privacy provisions after hearing concerns from a state liaison for the National Rifle Association.

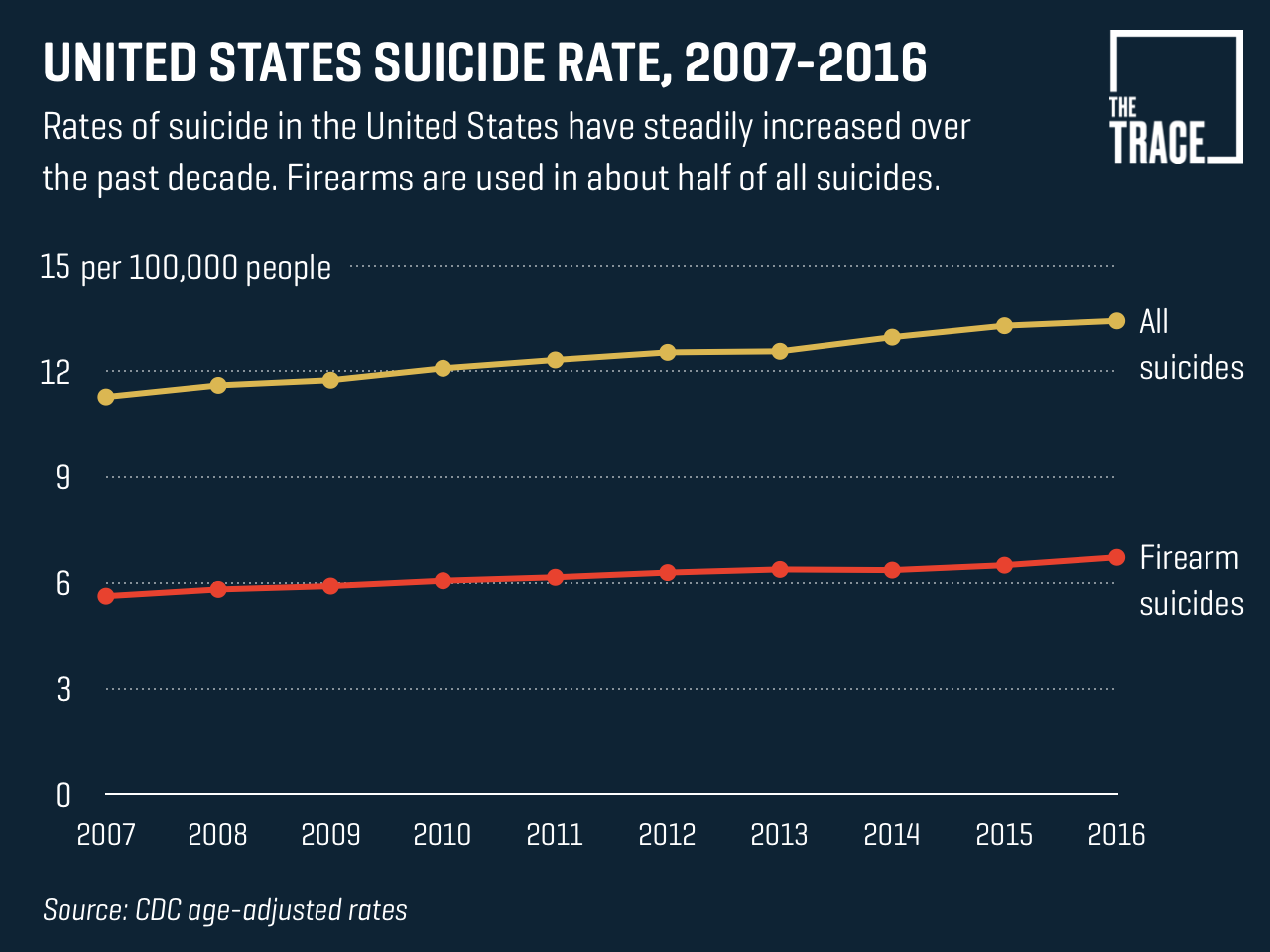

Suicide accounts for the majority of gun deaths in Washington. Between 2014 and 2017, the state had more than 3,500 firearms deaths, three-fourths of which were suicides. Research indicates that many suicide attempts are made in moments of grave distress, often following mere hours — even minutes — of deliberation. Survivors often do not try again. But guns, with their especially lethal power, rarely afford second chances.

In Washington, signing the bill was just the first step. Still remaining is the work of promoting the law. Five months after the policy was implemented, just three people have used it to suspend their gun rights, according to the State Patrol. None have filed to revoke their waivers.

“I assume that as more people become aware of it, more will use it,” Pedersen said. The Trace asked Pedersen, the state courts, and the State Patrol what agency is responsible for ensuring word gets out about the program’s existence. They each gave conflicting answers.

The state courts’ website specifies that county clerks, firearms dealers, and healthcare providers are supposed to make the waiver forms available at their locations, but “there is not a central office/agency that is specifically charged with ensuring compliance, to my knowledge,” wrote Wendy Ferrell, a spokesperson for the courts, in an email.

“I don’t think that was very well publicized to dealers,” said one gun shop owner in Kitsap County, who preferred not to be named. He was not aware of the waiver policy prior to being contacted by The Trace, but later wrote in an email that he had printed the forms and is making them “available for anyone who wants to do this.”

Gun violence prevention advocates say they want to help spread the word. “This is one of several suicide prevention tools that we are committed to making sure the public knows about,” said Kristen Ellingboe of the Washington Alliance for Gun Responsibility.

Brett Bass, a program coordinator with Forefront Suicide Prevention at the University of Washington and a part-time firearms instructor, views the waiver as a promising option for keeping people safe in moments of distress. He says his team has discussed promoting waivers as an alternative to extreme risk protection orders, which enable family members or law enforcement to petition a court to temporarily remove guns from someone at risk of harming themselves or others. ERPOs, says Bass, tend to be poorly understood by and polarizing to the gun owners his team is trying to reach. By contrast, he says, the voluntary waiver concept is more straightforward and “provides a lot more agency to the people who would theoretically be able to make use of it.”

If more people become aware of the policy, Vars and others believe it has the potential to save lives — potentially hundreds nationwide, by his estimate. A few years ago, Vars surveyed 200 psychiatric patients across three clinical settings in Alabama to gauge their receptivity to a “do not sell” list. He found that 46 percent of them would be willing to sign up. “I was like, holy shit,” he recalled. “At that moment it felt like I had to try to get it enacted in as many places as possible.”

Vars is still tweaking his model legislation and trying to get other states to adopt it.

When Washington’s bill was enacted, Vars didn’t spend a lot of time celebrating. Recalling it over the phone recently, he paused briefly, becoming choked up. The email from the Washington senator had arrived in his inbox last spring, casually announcing the measure been passed — the thought he’d been cultivating for years was now real. He felt ecstatic, vindicated. But only for a few days. “Then I said to myself, okay, that’s one. We got 49 more to go!”