This story was originally published in April 2019, and updated in August 2023.

Roughly a third of parents with school-age kids are very or extremely worried about gun violence at their child’s school, according to a 2022 survey by The Pew Research Center. And in much of America, the response to school shootings has been to put more guns in schools. The same Pew survey found that roughly half of U.S. parents think armed security in schools is an effective response.

Despite the prominent media coverage of mass shootings, and school shootings in particular, they account for just 2 percent of gun deaths. In 2022, there were 51 active shootings that caused injury or death — excluding suicides — in K-12 schools or on school buses. There are roughly 100,000 public schools in the United States, meaning that these incidents are quite rare. Still, widespread worry fuels an active national debate about how to curb these shootings.

A reader wanted to know, are armed guards — sometimes called school resource officers or school police officers — actually a deterrent to gun violence and mass shootings? We found the evidence is limited.

Have guns stopped mass shootings at schools?

There are only a handful of documented cases in which an armed security guard or stationed police officer has stopped a school shooting. A commonly cited example involves a school resource officer who chased a gunman off a high school campus in Dixon, Illinois, in May of 2018, then shot and wounded the perpetrator.

A recent study by researchers from The Violence Project suggests that armed guards in schools don’t reduce fatalities. Researchers examined 133 school shootings and attempted school shootings between 1980 and 2019, tallied up by the K-12 School Shooting Database. At least one armed guard was present in almost a quarter of cases studied, and researchers found no significant reduction in rates of injuries in these cases. In fact, shootings at schools with an armed guard ended with three times as many people killed, on average. “Whenever firearms are present, there is room for error, and even highly trained officers get split-second decisions wrong,” the researchers wrote. “Prior research suggests that many school shooters are actively suicidal, intending to die in the act, so an armed officer may be an incentive rather than a deterrent.”

A 2013 study conducted by the FBI analyzing 160 active shooter incidents found that most attacks are carried out in “a matter of minutes,” making it difficult for armed guards to be in the right place at the right time.

“Even when law enforcement was present or able to respond within minutes, civilians often had to make life and death decisions, and, therefore, should be engaged in training and discussions on decisions they may face,” researchers wrote.

For mass shootings more broadly, there’s evidence that unarmed bystanders have stopped more attacks in these early minutes than armed people. Researchers from ALERRT analyzed 249 shootings between 2000 and 2021 that ended before police arrived. Most ended with the shooter fleeing the scene or dying by suicide, but bystanders subdued the shooter without guns nearly twice as often (42 cases) as a bystander who shot them (22 cases).

In several notable instances, unarmed bystanders have successfully ended school shootings. An Indiana teacher stopped a student from firing a handgun in 2018 by throwing a basketball at him, then retrieving the gun. And in 2021, after a teacher in Idaho took a gun from a sixth-grade girl, she pulled the student into a hug.

“There tends to be this perception that the most effective solutions are the ones we can see,” said Jaclyn Schildkraut, the executive director of the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium at the Rockefeller Institute of Government. “But we don’t have any data to suggest that more than one person pulling a firearm in the middle of a shooting is going to be somehow any less bad or stop that completely.”

How many schools have armed adults on campus?

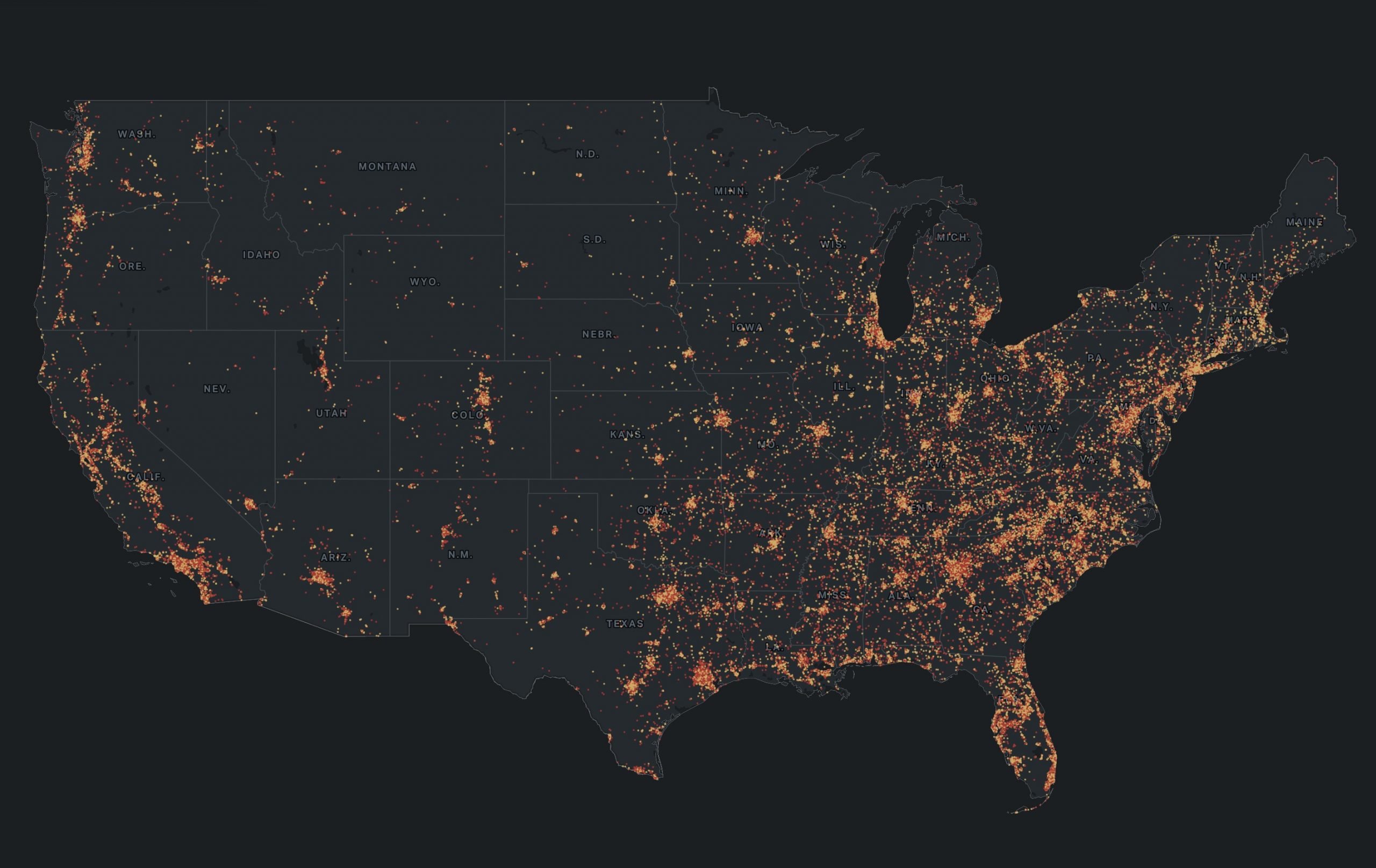

Guns in schools are a fact of life for millions of American children. Among 83,100 schools that responded to a National Center for Education Statistics questionnaire, more than 50 percent said at least one sworn law enforcement officer routinely carried a firearm at school during the 2019-2020 school year.

It’s important to note that individual states define these officers’ duties differently, with variations in what they’re called, training requirements, and even whether they are allowed to carry firearms. This particular survey asked about “career sworn law enforcement officers with arrest authority, who have specialized training and are assigned to work in collaboration with school organizations.” The total doesn’t include schools that might employ armed private security or allow teachers and administrators to carry guns on campus.

Arming teachers is a relatively popular idea — a 2022 poll conducted by Phi Delta Kappa International, a professional organization for educators, found that among 1,008 adults surveyed, 45 percent said they supported arming teachers. But teachers tend to feel differently: A recent survey by the RAND Corporation found that 54 percent of K-12 educators believe that arming teachers would make students less safe, while 20 percent think the opposite.

What about “gun-free zones”?

It’s an axiom of the pro-gun movement that mass shooters target “gun-free zones.” According to that logic, the presence of armed guards should deter shooters. Former President Donald Trump embraced that reasoning in a post-Parkland statement on school safety.

However, research by professor Louis Klarevas of Teachers College, Columbia University suggests there is little evidence that active shooters favor “gun-free zones.” Klarevas analyzed 111 shooting attacks between 1966 and 2015 for his book Rampage Nation. He found that only 18 took place in areas where firearms were banned.

Furthermore, the record doesn’t support the deterrence theory, as gunmen have often targeted schools with armed guards — who have failed to stop the gunmen from killing in several high-profile shootings over the past five years. This group includes those that occurred at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, and Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, Texas.

What effects do school security officers have on students?

Most guards will never encounter an active shooter. But they may carry guns around students every day on the job.

Students don’t necessarily feel comforted by police or other armed security. Instead, some have said they feel surveilled — particularly Black and brown children. The National Association of School Psychologists has argued that, like violence itself, the fear that results can harm the learning process.

Investigating America’s gun violence crisis

Reader donations help power our non-profit reporting.

One 2011 study concluded that as schools increasingly rely on police for security, administrators refer more students to law enforcement for nonviolent infractions. A 2021 study from researchers at SUNY Albany and RAND indicates that the presence of guards actually “marginally increases the likelihood of a school shooting” as well as chronic absenteeism, and the occurrence of other gun-related offenses. Researchers noted that the increased security presence may influence the latter, as well as a decrease in the likelihood of physical violence not involving firearms.

“This criminalization of school misconduct is particularly problematic when applied to Black students, given the stark existing racial disparities in arrest and incarceration,” wrote the researchers.

Police in schools may also end up using force against students. An investigation by HuffPost found that from September 2011 to September 2018, school-based police officers used tasers or stun guns on students at least 120 times.

“When you have proper vetting, and you have the right people in place, security, police, whatever you categorize them as or whatever their role is, can build really great relationships with students,” Jaclyn Schildkraut of the Rockefeller Institute of Government said. “But unfortunately, not every person who wears a badge or carries a gun belongs to the school.”

Who pays for armed guards in schools?

There’s no federal law that mandates armed guards in public or private schools. A 2013 study from Cleveland State University estimated that putting an armed officer in each public and private school in America would cost around $10 to $13 billion annually.

Some states have passed their own legislation: After a gunman killed three 9-year-olds and three adults at a private school in Nashville in March of 2023, state lawmakers passed a bill focused on school safety, and Governor Bill Lee amended his budget proposal, setting aside $140 million in funding to place an armed security guard at every school.

In June of 2023, a year after the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, Governor Greg Abott signed into law legislation that would station at least one armed security officer on every school campus — which some experts estimate could cost schools up to $100,000 for each officer employed.

On the federal level, Tennessee’s U.S. Senators Marsha Blackburn and Bill Hagerty introduced a bill in late March, 2023 that would provide $900 million in grants to schools that hire more school security personnel. If passed, the law would let states decide whether to arm officers.

What alternative policies have been shown to make schools safer for students?

Experts suggest focusing on physical building security. Schildkraut notes that in only three school shootings — at Red Lake Senior High School in Minnesota; Platte Canyon High School in Colorado; and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida — students were killed behind a locked classroom door. While the debate over approaches to school safety can be polarized, there’s broad public support for drills, training, and “school hardening” — which involves physical updates that make school buildings more difficult to enter.

Other experts have argued that schools would be better served by federal and state gun reform. In the meantime, they encourage schools to invest in more holistic preventive measures — including mental health training and resources, anti-bullying or social inclusion campaigns, and better threat assessments to catch or mitigate the warning signs that often presage a mass shooting.