On a cloudy August afternoon at La Villita Park in Chicago’s Little Village, a father chased after his toddler, young teens ate free hot dogs after a grueling game of softball, and a couple took over the dance floor as the banda played tamborazo.

They’d gathered for New Life Centers’ second-to-last summer event, part of “Light in the Night,” a safety strategy that Metropolitan Peace Initiatives and Communities Partnering 4 Peace developed to bring organizations together to host family-friendly activities to make public spaces safe.

Robert Trejo, a 14-year-old resident of Little Village, said his neighborhood has a reputation for being dangerous. Events like these let him “escape reality,” he said, and make him want to continue living there, to help make it safer for future generations.

“Light in the Night” and similar gatherings aren’t available consistently throughout the year, however, leaving a vacuum that young people say makes it harder to find positive environments to hang out in after school. The city’s Department of Family and Support Services and several private organizations ramp up youth programming in the summer for obvious reasons — children and teens are on school break — but also because that’s when gun violence peaks.

Organizers who provide youth programming said the work they do, like mentoring, civic engagement, and emotional learning, can save lives if they’re able to reach young people at pivotal moments. But as summer turns to fall, many programs end, and events meant to provide a safety net for Chicago’s kids and teens become less frequent. The Trace spoke to more than a dozen organizations and a dozen young people. Most teens and young adults said there is not enough accessible and effective programming offered during the school year.

“We not just youth in the summertime, life goes on around the year,” said Tyree Belfield, a 24-year-old resident of Englewood. Belfield, like other youth and young adults interviewed, said that, during the summer, organizations entice them with interesting jobs and activities that end abruptly when the school year starts.

Investing in youth programming all year round

Not everyone understands the potential that after-school programming has to reduce violence, said Jodi Grant, executive director of Afterschool Alliance, an organization that researches and advocates for more summer or after-school learning opportunities. “Far too many people think of after-school as childcare.”

Youth programming often incorporates mentoring, community service, and cognitive behavior therapy into its curricula. Access to extracurricular activities, Grant said, gives youth opportunities for relationship building, academic enrichment, behavioral growth, and self-exploration. Studies show that participation reduces delinquent behavior and that the “prime time” for juvenile crime is between the hours of 2 and 6 p.m. — immediately after school.

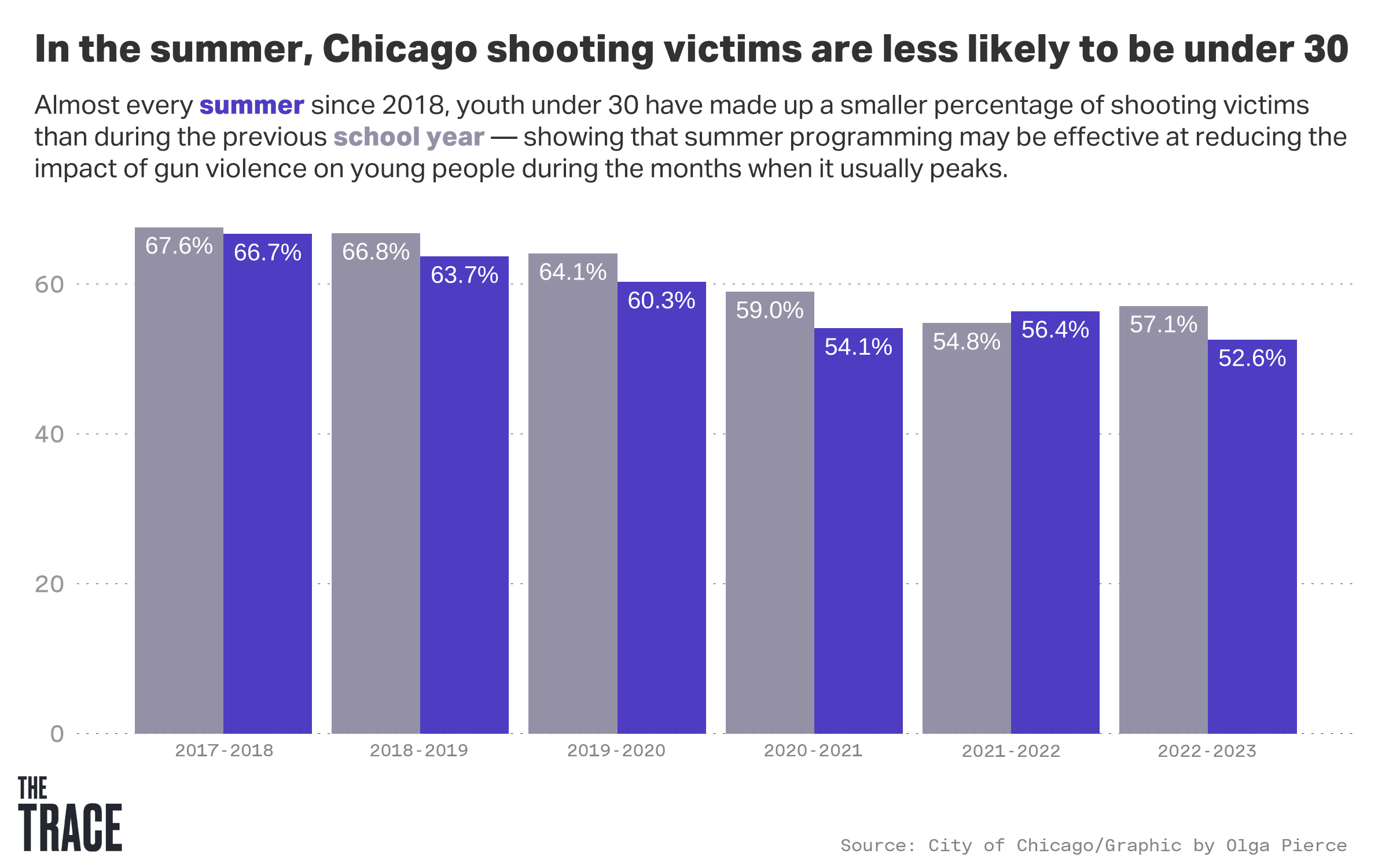

Over the past decade, children and young adults through age 29 have comprised almost two-thirds of the city’s shooting victims, according to data from the Chicago Police Department. To mitigate the effects of the most violent months of the year, the city and organizers provide programming to redirect them into positive environments.

At Mr. Dad’s Father’s Club summer camp, for example, founder Joseph Williams tries to gauge participants’ interests and expose them to different opportunities and people, including taking a boat ride to learn about jobs in tourism and meeting a Chicago judge to learn about the criminal legal system.

“It makes me feel like one day, I could be in that position,” said Belfield. “Being around and seeing other people like me, my color, in those seats, in those offices, doing stuff like that, that come from the same place we come from. It’s inspiration.”

But there’s a disparity in who can access programming year-round. “So many kids are being left behind because they can’t afford it,” Grant said. “Publicly funded programs don’t have enough resources to serve more kids.” Data from the Afterschool Alliance shows there is an unmet demand for afterschool programs. In Illinois, for every child in afterschool, four are waiting for an available program.

“We are [operating] in some of the most underinvested, disinvested communities in Chicago,” said Tara Dabney, director of development and communications at the Institute for Nonviolence Chicago. “So we don’t have a lot of after-school programs or a lot of safe spaces.”

Prioritizing the summer

Many youth employment programs often take place in the summer, either on a small scale, such as the 115 teens employed by Legacy Disciple’s Hood Heroes this summer, or on a larger scale, such as the City of Chicago’s One Summer Chicago program, which employed over 20,000 teens and young adults last year.

A 2018 study showed that summer youth employment programs are effective in reducing arrests for violent crime, incarceration, and premature deaths. Its research into a randomly selected group of 2012 and 2013 One Summer Chicago participants found that the program reduced the number of violent crime arrests by 35 percent one year after the program.

That’s why there’s a spike in funding for youth programming during the summer, said Matt DeMateo, executive director of New Life Centers. Organizations like the Partnership for Safe and Peaceful Communities (PSPC) and the Obama Foundation’s My Brother’s Keeper Alliance’s Freedom Summer initiative dole out summer-specific funding. Earlier this year, Mayor Brandon Johnson worked with PSPC to expand its Chicago Fund with $2.5 million to target specific summer dates.

Limited resources, DeMateo said, need to be allocated where they’re most needed. “There’s not an unlimited well,” he said. “The strategy targets when historically, violence is the highest.”

In general, data indicates that resources and programs offered in the summer are effective at reducing gun violence during that time frame. For the most part, with the exception of three years, Chicago Police data shows that every year since 2013, a smaller percentage of people age 29 and under have been impacted by gun violence each summer than during the previous school year. But then it goes up again.

“Youth engagement year-round is what’s needed to create the sense of community, the sense of safety,” DeMateo said. “If you only have limited resources and access to positive things a certain few months of the year, then the rest of the year, you’re going to have a massive gap.”

Taking matters into their own hands

Gun violence across Chicago, mostly concentrated in disinvested and disadvantaged communities, has affected the way young people of color are able to gather and socialize within their neighborhoods. A recent WBEZ analysis found that there are limited recreational options available for youth in areas outside Downtown Chicago.

Those who can’t find programming, especially Black teens, have organized their own meetups Downtown, often called “trends” or “teen takeovers.” While many have said they join these events to socialize with friends, some have become violent, leading people on social media to condemn young people in general, and to assail them with racial epithets.

But kids and organizers interviewed by The Trace said that young people are just looking for a sense of belonging in their communities. “A lot of us, believe it or not, struggle with anxiety,” Belfield said. “A lot of people don’t know how to articulate themselves well, so it might come off [as rude].” But, he said, if people just sat down and talked to young people, they would understand them.

Studies show that safe places are necessary for the resiliency of Chicago teens who live in high-crime neighborhoods. They also demonstrate that investment in public areas like parks and libraries can reduce gun violence.

Organizers said they try to provide these havens through programming. Several have done so for years, said Tamar Manasseh, founder of Mothers and Men Against Senseless Killings, regardless of whether they get any funding. Her question is: What is the city’s role?

Organizations like hers, she said, guide youth, but when they ask the city to provide jobs for them throughout the year, the city falls short. “So those kids usually end up doing whatever they were doing, prior to receiving these really valuable skills, to survive,” she said. “That normally leads them to one of two places — the cemetery or jail.”

Finding solutions

Despite limited funding, some organizations are finding creative ways to continue their relationships with youth or offer new programs.

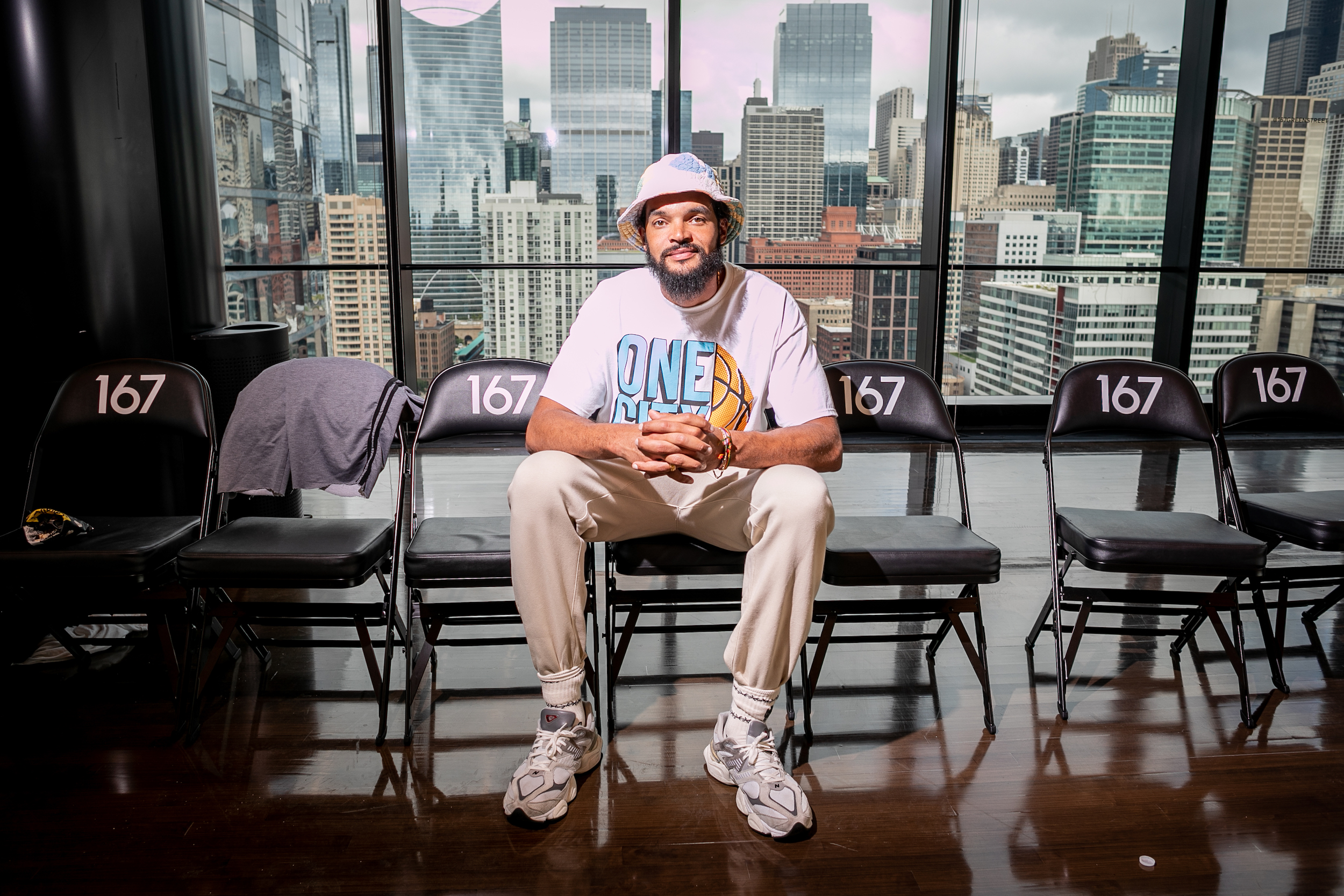

Some organizers, like Cobe Williams, director of National Programs for Cure Violence Global, are collaborating with other groups. This summer, he and Joakim Noah, the co-founder of Noah’s Arc Foundation and a former Chicago Bulls basketball player, launched One City Basketball League. The program ran from May to August, with 280 players ages 16 to 25.

“Basketball is like a hook,” Williams said. It brings people together, he added, but the long term goal is to educate the participants about violence prevention and to provide them and their families with long-term resources to cope with everyday life.

With a high demand for the league to run year-round, organizers decided to bring it back in January 2024. Even in the break between August and the start of next year, Williams said, they plan to provide workshops.

Other organizations limit the number of young people they work with and provide one-on-one mentoring throughout the year. Marcus Mathews, a participant of Mr. Dad’s Father’s Club’s summer camp, has been working with Joseph Williams, its founder, for over a year. “All of us are like family,” Mathews said. “We stick together.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Tyree Belfield’s age.