New York State Senator Zellnor Myrie was on bedrest with a throat illness in the summer of 2020 when he flipped open his laptop to do some internet digging. The tumult of the pandemic was fueling historic rises in gun crime in his Brooklyn district and others like it across the country. He couldn’t speak, and couldn’t get out onto the streets to render aid to his constituents, or to attend funerals. Perhaps, he thought from his bedroom, history would have some clues as to what the Legislature could do to stymie the surge.

He started reading old lawsuits against the gun industry, and eventually wound up at the Congressional Record from July of 2005. That month, the Senate voted on the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA, pronounced “plack-uh” for short) — the bill that would, by the year’s end, grant the gun industry special legal immunity from most lawsuits filed over crimes committed with their products. The deliberations pointed him to an exception written into PLCAA, which allows lawsuits when gun companies violate state or federal laws “applicable to” the sale or marketing of firearms.

For 15 years, activists and victims of violence had tried to use PLCAA’s exception to sue gun companies, hoping liability would drive reform. They almost never succeeded. Myrie’s research showed him that judges had mostly decided the law’s exception meant a company needed to break a law specifically about guns, not a general law that may in some cases apply to guns. Failed suits had argued that reckless distribution and marketing practices had facilitated widespread trafficking, which violated general public nuisance or deceptive trade laws.

Still, Myrie thought, this seemed a simple enough problem to solve. Plaintiffs needed a law that explicitly regulated gun sales or marketing. Couldn’t he just pass one?

“I remember there was almost a level of alarm around the simplicity of the idea,” Myrie told The Trace of the reaction from gun violence prevention activists he consulted while writing his bill. “[They] kept asking me: ‘If this were so simple, why hadn’t any other state taken the step?’”

Myrie settled on a straightforward solution: A bill that required gun companies to more carefully monitor the distribution and marketing of their guns. It mandated that companies implement tighter security and screening during sales, stricter inventory controls to prevent theft, and policies to curb false advertising. It didn’t prescribe a one-size-fits-all policy solution each business needed to enforce to get that done, so companies could devise such policies on their own. If widespread gun trafficking and violence continued, victims would have an opportunity to argue that the policies hadn’t worked — in court.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul signed Myrie’s bill into law in July of 2021 and in the two years since, versions of the legislation have been adopted by states across the country. On August 12, Illinois became the eighth state to enshrine some version of the legislation into law, joining Colorado, Washington, Hawaii, New Jersey, Delaware, and California in addition to New York. A ninth bill is currently being considered in Maryland.

“This has the potential to revolutionize the field of gun violence prevention,” said David Pucino, deputy chief counsel at the gun violence prevention group Giffords, who was an early architect of the legislation. “It will allow us to finally target those bad actors who we know are disproportionately responsible for the number of crime guns on our streets.”

The National Shooting Sports Foundation, the gun industry’s trade group, has challenged several of these laws in court, calling them “an abuse of the legal system.” The original version was upheld in New York last year and a modified version struck down in New Jersey, though both decisions have been appealed. Challenges are pending in Delaware, Hawaii, California, and Washington. NSSF did not respond to a request for comment.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, guns have been used in more than half a million killings since 1968. Studies have shown that the guns used in that violence tend to come from a tiny proportion of dealers: By one 1998 count, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives found that roughly 7 percent of dealers had accounted for about 90 percent of guns found at crime scenes.

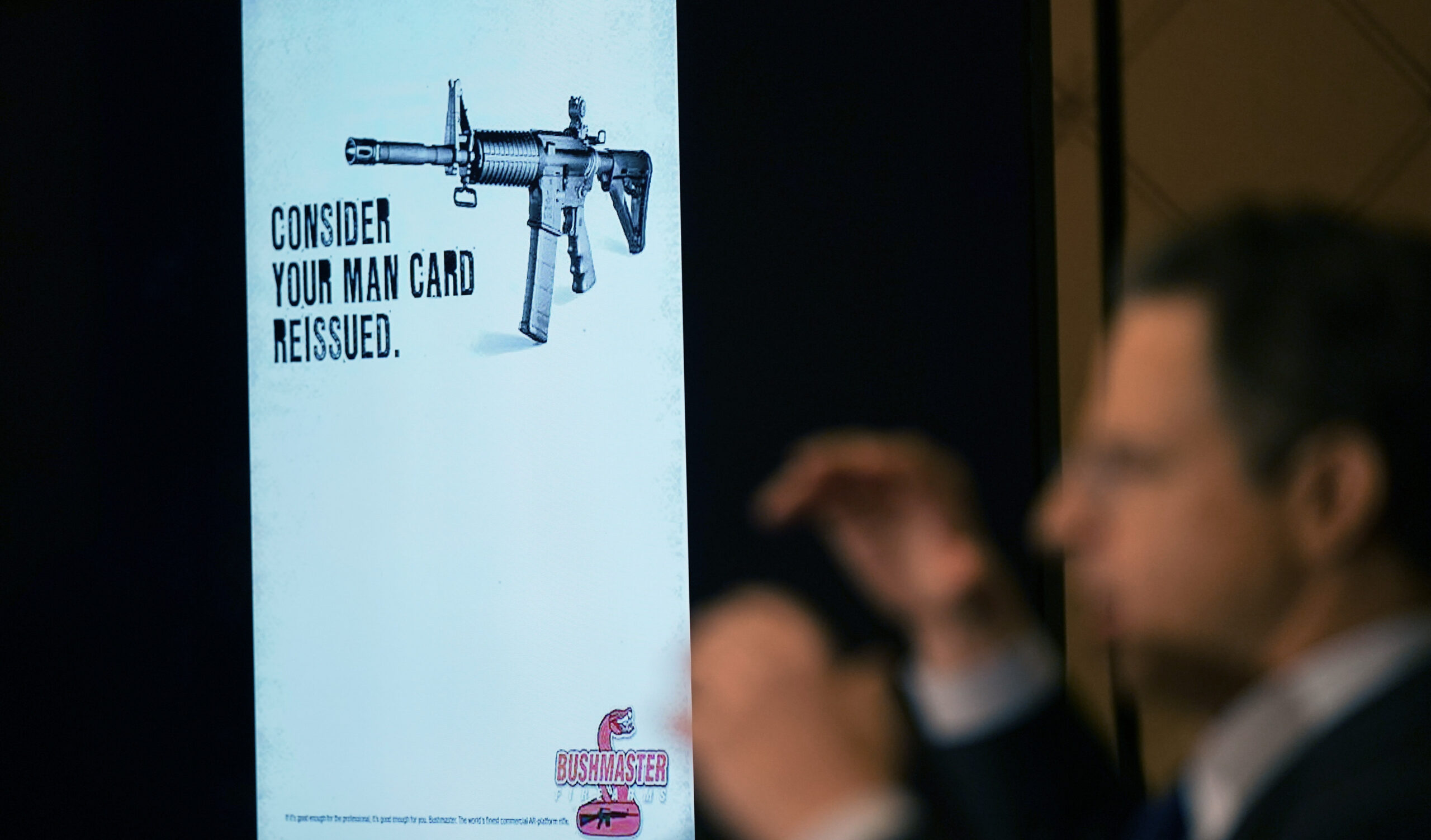

Gun violence prevention advocates like Pucino and the shooting victims he represents have long believed that the firearm industry could do more to interrupt the flow of guns that enables these shootings. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, city governments and violence prevention groups attempted to force reforms through the courts, arguing that gunmakers had ignored data about bad-acting retailers and oversupplied certain markets while knowing that surplus guns would be diverted to trafficking networks. The arguments persuaded several judges, who wrote scathing opinions condemning gun manufacturers and distributors who “failed to take minimum circumspect steps to limit leakage of their guns into criminal hands.”

But few suits had their day in court. In 2003, the industry successfully lobbied to restrict access to the gun trace data that served as the backbone of cities’ legal arguments. And in 2005, another successful lobbying effort led to the passage of PLCAA. Within a few years, all but one of the suits was thrown out.

PLCAA meant that, in most cases, gunmakers could no longer be sued for crimes committed with their weapons — even if victims alleged that reckless sales practices had put guns in shooters’ hands. Its exception, allowing for suits that allege violations of relevant state and federal statutes applicable to gun sales, has occasionally opened the door to liability claims: The city of Gary, Indiana, for example, was allowed to continue its two-decades-old suit against major gun manufacturers after arguing that the companies’ conduct violated a state public nuisance law. And Sandy Hook victims’ lawsuit against the gunmaker Remington proceeded on the grounds that the company violated a general state marketing law. But these successes are rare — by and large, courts have decided that more general laws governing commerce don’t meet the “applicable to” standard.

Myrie’s bill and the spate of statutes modeled after it aim to resolve this ambiguity.

Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul, who drafted his state’s bill, said, “We’re making it clear that our already-existing consumer fraud law applies to the gun industry, too.” The legislation, passed in May, revised Illinois’ Consumer Fraud and Deceptive Practices Act to require that gun companies implement security and screening procedures to prevent sales to minors and straw purchasers. “We’re either going to make these gun companies change their practices such that they’re not unlawfully marketing to kids or selling to straw purchasers, or shut them down.”

So far, only New York’s law has been invoked to sue gun companies. Shortly after a federal judge cleared the statute to take effect, Attorney General Letitia James and city governments in Buffalo and Rochester, respectively, filed suits naming dozens of gunmakers who they allege contributed to a public nuisance in the state by negligently marketing and distributing their products. James’s suit focuses on ghost gun retailers, while the Buffalo and Rochester suits challenge major gun manufacturers and wholesalers for fueling a rash of deadly shootings.

The city suits were consolidated and stayed in June, pending an appeals court ruling over the statute’s constitutionality.

The laws modeled on Myrie’s differ slightly from state to state, but all of them were crafted to give attorneys general, city governments, or private citizens a legal foothold when trying to sue gun companies for violence.

In New Jersey, for example, only the attorney general can sue, as opposed to the private right of action granted to civilians in the rest of the bills. In Colorado, the law simply clarifies that an already on-the-books consumer protection law applies to the firearm industry, and Washington’s law states that longstanding public nuisance and deceptive advertising statutes can be invoked to sue gunmakers for violating the new standard of conduct.

Each of the statutes contains stipulations that appear redundant. It is a federal crime, for example, to sell a gun to a straw purchaser or a felon, so many stores already implement training and sales practices to prevent such transactions. But legislators and assistant attorneys general told The Trace that the new standards of conduct open the door for victims of gun violence to pursue lawsuits and potentially win civil damages.

Kristin Beneski, Washington’s first assistant attorney general, said that the pathway to justice available through the state’s new law would again allow legal victories like those won by victims of the Washington, D.C., sniper killings in 2002. In that case, families were able to sue the Tacoma, Washington, gun store that sold the rifle used in the D.C. shootings, along with the gun’s maker, which had ignored warning signs that the store was operating recklessly. The store, Bull’s Eye Shooter Supply, had lost track of hundreds of weapons, including the killers’ sniper rifle, and failed to report the missing inventory to authorities. The families won a $2.5 million dollar settlement.

“If you or a member of your family has been personally hurt by gun violence attributable to the irresponsible conduct of a gun company, this law will allow you to get damages — to get money that can go towards remedying your injury,” Beneski said. “After the PLCAA, you need one of these laws to enable that kind of recovery.”

Another change to the legal landscape makes it unclear how, exactly, these laws will play out. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, when lawsuits against gun stores and major gunmakers were common, plaintiffs often relied upon gun trace data from the ATF to prove that gun wholesalers or manufacturers had sold their guns to stores they should have known were acting irresponsibly. But since 2003, an amendment to federal law called the Tiahrt Amendment has barred that data from public disclosure, leaving plaintiffs with few tools at their disposal to prove misconduct.

Hawaii State Representative David Tarnas, who authored his state’s bill, acknowledged this limitation, but said he was working to shore up whatever gaps may exist in the state’s available data on crime guns. Delaware State Senator Bryan Townsend, the author of his state’s bill, said he imagined that many cases would originate with violations at the retail level, pointing to the example of a Christiana-area Cabela’s that lost half a million rounds of ammo in less than a year in 2023. “This of course doesn’t automatically mean that someone upstream is liable,” he said, “but discovery could indicate that wholesalers or manufacturers were aware of or indifferent to indications that the inventory was being misplaced.”

The law may meet its most rigorous test in California, where access to much state level crime gun tracing data is not controlled by the federal government. There, guns sold at stores in California and later recovered by California police can be tracked by the state government without the assistance of the ATF, meaning the data may not be subject to the same restrictions as federal gun trace records.

A spokesperson for the California Attorney General’s Office could not currently clarify whether the state’s crime gun data would be usable in court, but said the office will use whatever data it has at its disposal to help guide investigations into gun companies that run afoul of the new standards. The data is compelling: A report published by the Attorney General’s Office in June of 2023 found that 4 percent of the gun retailers in the state accounted for more than half of the California-sold crime guns recovered by police between 2010 and 2022 — nearly 40,000 weapons in total.

For Myrie, evidence that thousands of crime guns trace back to just a small handful of dealers underlines the fundamental gap in the gun violence prevention toolbox that his law aims to patch. “We don’t make guns in Brooklyn,” he said. “Yet everybody has access. It comes back to the same questions: Where are the guns coming from? And what am I gonna do about it?”