Janet Foster lost two children this year. One night in late July, she woke to the sound of gunfire outside her home on the East Side of Cleveland. She rushed out the door to find her 22- and 26-year-old sons lying in her neighbor’s driveway. They’d both been shot. She shouted for help, but none came. Her sons died before doctors could intervene.

In the months that followed, Foster struggled to cope with her loss. “Some days I can’t do nothing but be locked up in my room because the pain is so severe,” she said. “I’ve been here eight years, and I’ve never seen violence so bad.”

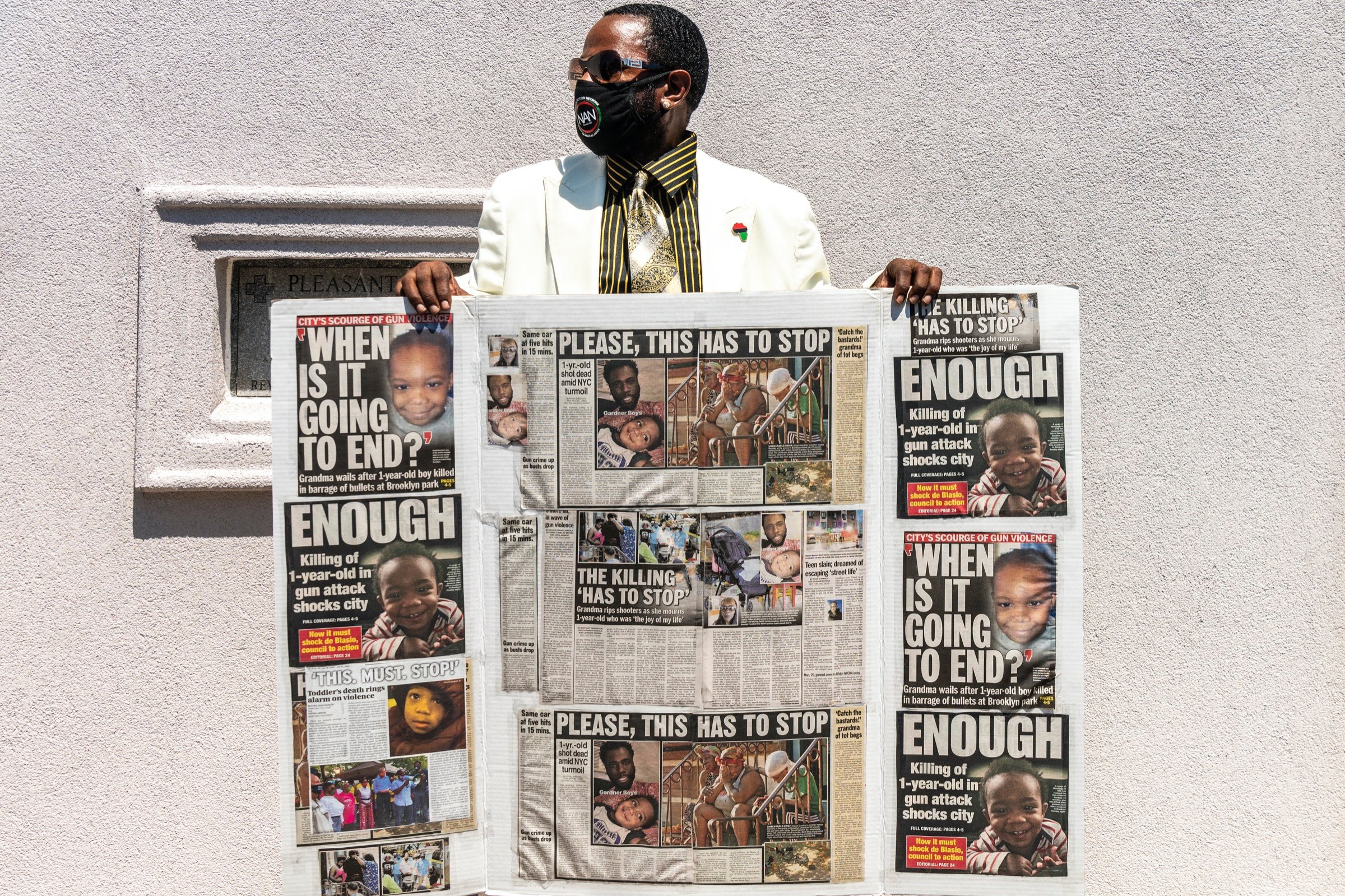

Foster’s sons, Delvonte and Domenique King, were among a record number of people killed in Cleveland this year, making the city one of dozens that battled sharp increases in gun deaths. From Oakland to Chicago to New York City, homicides and shootings crept toward — and sometimes exceeded — all-time highs. The sudden upswing reversed decades of progress, and provides a prism for the intersecting crises that characterized 2020. While researchers are still picking over the causes, the consequences of the violence are plain: Thousands of communities, families, and parents like Foster forced to manage terrible voids — and saddled with the knowledge that at any moment, more gunfire could tear open new ones.

In some communities, violence was already soaring when the pandemic prompted statewide lockdowns. Philadelphia, Houston, and Memphis tallied 10 percent more homicides between January and March than in the same period in 2019. The problem was even worse in Milwaukee, where killings doubled.

Rusti Pendleton, a violence intervention worker at Boston Medical Center, saw the costs of this violence at the bedsides of shooting victims, where he urged them to put down their weapons and enlist the help of a caseworker. He worried that the pandemic would inflame the first-quarter homicide increases, and he was right: By July, homicides in Boston had surged 40 percent over the previous year. The interplay was readily apparent at the hospital, where two out of every 10 shooting victims tested positive for COVID-19, forcing Pendleton to keep his distance. “They would be whisked off to another part of the hospital, and for the safety of my own family I gotta choose not to deal with that,” he said.

Similar scenes played out across the country as social-distancing measures handicapped violence intervention groups and shuttered community programs designed to keep young people occupied during the summer months. The pandemic snuffed out “just about every positive source of social connection or mental health outlet available to these communities most at risk for gun violence,” said Lisa Fujie Parks, an associate program director at the Prevention Institute, a national anti-violence nonprofit.

In some cities, the violence has overtaken the pandemic as the chief concern among locals. Ricky Vasquez, a Republican precinct chairman and City Council candidate in Fort Worth, said that, since a mass shooting in May, residents in his neighborhood haven’t felt safe walking to the store. He said their fear is driven less by the risk of contracting coronavirus than of the likelihood they’ll be shot. With homicides reaching into triple digits, Fort Worth has suffered a level of bloodshed not seen since 1995. “The last City Council meeting, we were at something like 87 homicides, and then all of the sudden just recently we found out we’re over 100,” Vasquez said. “People are wondering if they’ll survive.”

Likewise, in Philadelphia, the City Council has called on the mayor to declare gun violence a citywide emergency. City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier proposed the resolution in September. It passed a day after four people were shot — two of them fatally — at a basketball court near Center City.

Gauthier told The Trace that gun violence was not being treated as seriously as the coronavirus, even though both were exacting a disproportionate toll on the city’s Black residents. “I want to see us mobilize on gun violence in the same way that we mobilized on COVID-19,” she said. “All of these young Black people who are dying and getting shot at every day deserve the same level of priority and action.”

Many city leaders see more law enforcement as a balm for the killing. Albuquerque, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, Memphis, Milwaukee, and Kansas City, Missouri, accepted millions in federal grants through a Trump administration initiative to beef up local police departments, and many other city police departments have used the uptick as justification for inflating their budgets.

But this year’s police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd undercut the idea that increased policing makes communities safer. A national movement to defund police departments and redirect money to a robust social safety net emerged, and cities like Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Austin, Texas, and Seattle announced plans to slash police department budgets and steer the savings toward social services and community programs.

The increase in murders is “exactly why we made the changes to the police budget that we decided to make,” said Austin City Councilman Gregorio Casar, who successfully pushed this year for $150 million in cuts to the local police budget. “We need to change our budget to treat the economic and public health disaster that we’re dealing with.”

Police spending ballooned into one of 2020’s most contentious subjects — causing particular unease in cities with dramatic upticks in shootings. Opponents of the idea have expressed concern that shifting resources away from police during a crime wave will only abet violence.

In Portland, Oregon, for example, a sharp rise in shootings has sparked calls to restore a disbanded gun violence response team. And in Syracuse, New York, a constant drumbeat of shootings has left residents and local activists nervous that a weakened or absent police force will leave them defenseless. After a mass shooting in the city this June, Rashawn Sullivan, a local outreach worker, took to Facebook with his frustrations: “If you think it’s out of control now,” he cautioned, “watch when they defund the police.”

As the pandemic raged on, however, Sullivan and other workers on the front lines warmed to the logic behind redistributing police dollars. By December, he said it was plain that the coronavirus had laid bare gaps in the city’s social safety net that police money could fill. “Hurt people hurt people,” he said. “We don’t even have any sort of spiritual healing center in the city for all these people who have been traumatized over the years.”

A true consensus may never emerge about what precisely is driving the increases in gun homicide, though criminologists have scrambled in recent months to sift through contributing factors. The most obvious culprit is the coronavirus. Shani Buggs, a violence prevention researcher at the University of California, Davis, said studies have linked increased homicides to income inequality, housing insecurity, hunger, and unemployment — all of which the pandemic exacerbated.

“It is difficult on the research side to be able to draw these connections concretely,” Buggs said. “But what we know is: When you look at communities that have low rates of gun violence, they don’t have police on every corner. They have stable homes and safe places for people to work and play. They have supportive options for youth. They have quality schools. When people’s needs are met, they are safer.”

Richard Rosenfeld, a University of Missouri-St. Louis criminologist who examined 2020 crime trends for the Council on Criminal Justice, a nonpartisan think tank, said another issue is that cities have continued to resist calls for major police reform. Officers’ attempts to quash protests triggered by this year’s high-profile police shootings further eroded community trust and may have made people reluctant to involve law enforcement in their problems, fueling tit-for-tat shootings. Some policing strategies are demonstrably effective at driving down shootings, but these were likely hobbled as the virus reduced police staffing and forced officers to avoid close community interactions.

Crime statistics from the fall suggest that the rise in violence is ebbing, and Rosenfeld said he expects any spikes in the months ahead to be smaller than the massive surges that cities endured over the summer. Still, “this year will end with the largest year-to-year increases in homicides and firearm violence that we’ve seen in decades — at least,” he said. “It’s very likely that these increases are larger than any on record.”

For Janet Foster, who lost her sons in Cleveland, even a dramatic reversal would not bring complete peace. She clings to her boys’ memory. Delvonte was a “jokester and a workaholic” who was honest even when honesty was uncomfortable. “If you asked him a question,” she said, “you better make sure you wanted an answer.” He had plans to move in with his girlfriend this past fall. Domenique was an aspiring rapper with “a charisma about himself.” He lived with his girlfriend and three sons.

No one should have to carry their children only in memory, Foster said. “I’m trying to find a way — trying to figure out: How can we get together and stop all this?”