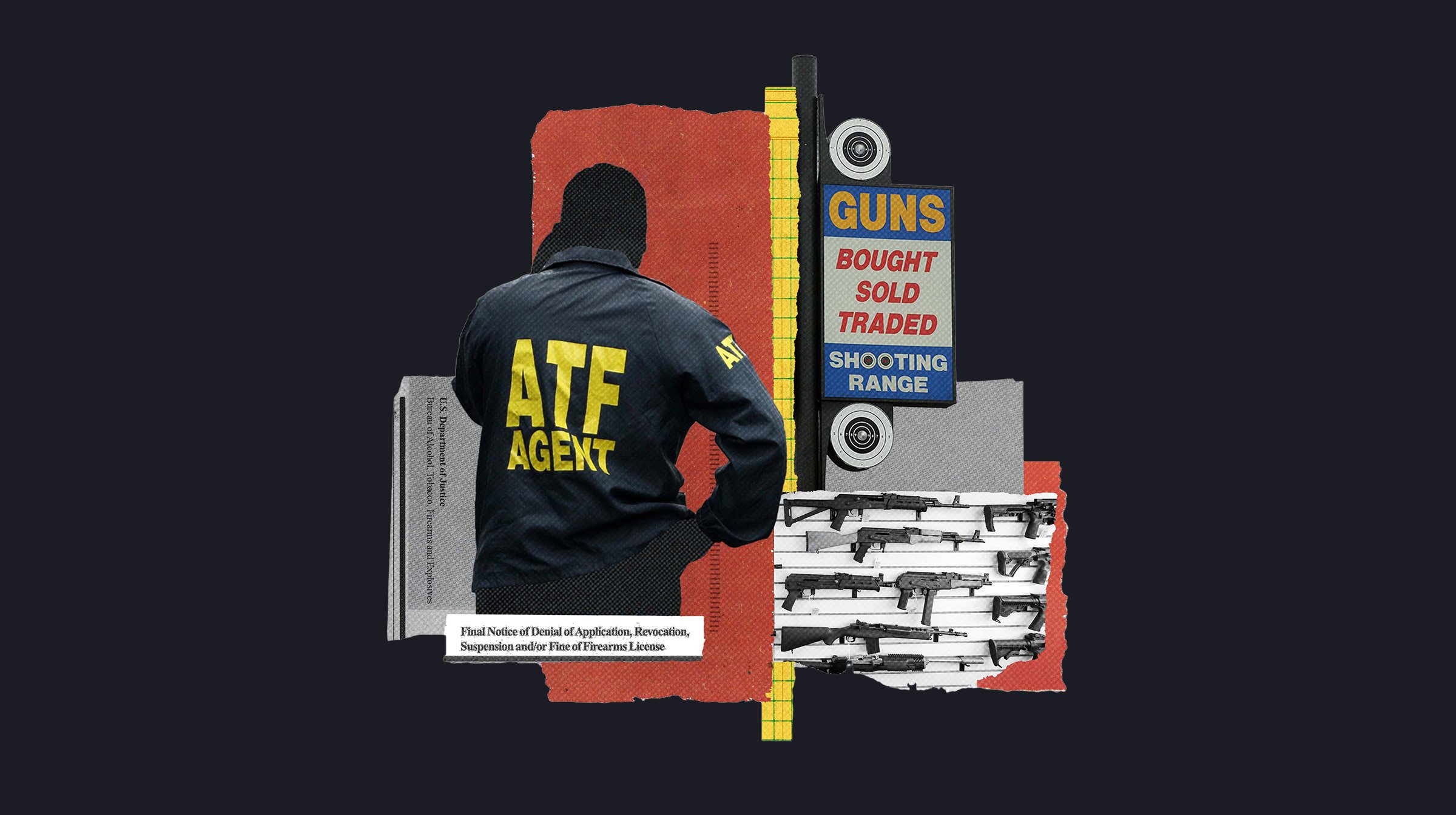

One gun store had hundreds of firearms missing from its inventory. Another transferred a weapon to a convicted felon in a parking lot. Many more sold guns to prohibited buyers or without properly conducting background checks.

The sweeping analysis that uncovered these law-breaking gun dealers was possible only because the gun control organization Brady waged a years-long legal fight to compel the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to produce records that, by law, should be public.

The nearly 2,000 gun dealer inspection reports analyzed by The Trace and USA TODAY provide an unprecedented look inside the ATF’s regulation of the firearms industry. They also represent less than 2 percent of the inspections conducted in the past decade. The full extent of gun dealers’ noncompliance, and of the ATF’s failure to regulate them, remains unknown.

The ATF’s production of documents related to Brady’s Freedom of Information Act request is still ongoing. On June 3, the agency acknowledged in a filing that even the core set of inspection reports analyzed by The Trace and USA TODAY was incomplete, adding that “determining which reports are missing will take more time than originally anticipated.”

The slow and inconsistent production of documents is consistent with what activists, lawyers, and former employees say are widespread problems with the ATF’s FOIA program. A law enforcement and regulatory agency, the ATF frequently breaks or ignores public information law, making it harder for citizens, journalists, and researchers to monitor its effectiveness.

On June 23, as part of a sweeping new effort to combat gun violence, the Biden administration directed the ATF to release more detailed information about the inspection process. The new data will contain inspection counts and outcomes broken down by the agency’s field divisions. The White House said the measure was intended to “promote transparency and accountability for the enforcement of our existing gun laws.”

The reforms will bolster access at an agency with one of the worst track records when it comes to producing public information, federal data shows. The ATF routinely takes months or years to fulfill even basic FOIA requests and sometimes ignores them altogether. Many of the more complicated requests only receive a response when filers take the ATF to court, as Brady did — a costly process out of the reach of most people.

Josh Scharff, legal counsel for Brady, said the ATF’s poor record-keeping systems limit its ability to respond to FOIA requests in a complete and timely manner.

“I would start by putting a lot of the blame on Congress for passing laws that restrict the ATF’s ability to manage its own data, while also under-resourcing the ATF,” he said. “At the same time, it’s incumbent on the ATF to do better, and it can do better with what it has, to manage its own data and information.”

During the course of The Trace and USA TODAY’s reporting, ATF spokesperson Andre Miller dismissed the notion that the agency’s inspections process is secretive, saying that the information is available to the public via FOIA. However, FOIA logs show that attempts to get information from the agency often fall short. In 2020, the ATF received about 1,200 requests and failed to respond to more than 250 of them. It also failed to fulfill nearly 20 requests filed by The Trace and USA TODAY over the course of their investigation.

In a statement, the ATF acknowledged problems, but said the situation had improved in recent years. ATF spokesperson Erik Longnecker said the agency’s disclosure division had reduced its backlog to the lowest level since 2013, and that the division slashed the average processing time by 41 days last year.

“We continue to improve our information-sharing capabilities,” Longnecker said. “We acknowledge that there is still room for improvement. ATF, in direct coordination with the Department of Justice, has made considerable investments.”

Access to public records sheds light on the ATF’s failings and its achievements, yielding valuable information for elected officials, voters, and victims of gun violence. ATF employees also use public information requests to prove evidence of internal mistreatment, misconduct, retaliation, or wrongful termination. Reporters, activists, and lawyers use FOIA routinely to probe the agency’s inner workings and spotlight problems in need of fixing.

Gunita Singh, a legal fellow for the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press, said the slow trickle of information provides a significant obstacle to the public’s understanding of gun violence, a topic of increasing concern among Americans.

“The sheer pervasiveness of [gun violence] requires robust dialogue and action, and can only take root when the public is as informed as possible,” Singh said. “If a federal agency takes months to years to respond to a records request or cites a baseless exemption to withhold records, that’s a major problem.”

In a declaration filed in the Brady lawsuit, Adam Siple, chief of the ATF’s information and privacy governance division, detailed the agency’s haphazard efforts to speed up FOIA processing. After the House Committee on Oversight and Reform asked for similar records to those requested by Brady, the agency reassigned some of its inspectors normally charged with visiting gun stores to help work on the request.

Siple said he believed the extra hands would allow the ATF to stay on schedule to produce the reports. But the idea backfired, he wrote, with inspectors’ work so inconsistent that senior records staff had to redo it, negating “any benefit associated with the detailees” and further slowing down the process.

Some current and former ATF employees said the agency obfuscates to avoid embarrassment. The agency has often drawn criticism from both sides of the political aisle related to failed enforcement operations and its regulation of firearms.

In 1993, the ATF came under fire for its assault on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, setting off a firefight and a weeks-long siege that resulted in the deaths of dozens of people. More recently, the agency faced scrutiny for a botched effort — known as Operation Fast and Furious — to track guns flowing from the United States to Mexican drug cartels.

The ATF has also become an easy target for pro-gun lobbyists, whose Republican allies have effectively stopped the agency from updating its record keeping systems and left it with consistent staffing shortfalls. Since 2003, a budget provision known as the Tiahrt Amendment has blocked the ATF from using federal funding to release information about traces of crime guns, a restriction that Scharff says the agency has embraced.

“The ATF absolutely does take an unnecessarily expansive view of Tiarht’s restrictions on releasing data that it collects and maintains,” he said. “And as a result of that, the ATF fails to release data and information on firearms trafficking and gun industry behavior that the public has a right to know.”

The ATF currently faces 16 pending FOIA lawsuits, according to The FOIA Project, a FOIA accountability database maintained by Syracuse University.

In 2017, Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting filed a lawsuit after the ATF stopped responding to a FOIA request seeking statistics on guns used in crimes. The ATF argued that querying the database containing the requested information would violate federal law.

If the ATF’s argument had been upheld in court, it would’ve given legal standing for all federal agencies to withhold any information held in an electronic database. Instead, in 2020, a 9th Circuit Appellate Court ruled against the agency.

“Were we to agree with ATF… we may well render FOIA a nullity in the digital age,” Judge Kim Wardlaw wrote in the majority opinion.

The case alarmed advocates and attorneys focused on freedom of information.

“We saw extreme pushback by the agency that risked thwarting transparency in drastic ways and well beyond just withholding ATF data,” said D. Victoria Baranetsky, Reveal’s general counsel who litigated the case. “This opacity handicaps constituents as well as legislators from having knowledge that is relevant to legislative decisions on public safety.”

In fiscal year 2020, the ATF processed about 1,600 FOIA requests, according to federal data. Federal agencies are required to respond to requests within 20 business days, though few meet this deadline.

Among the 76 federal agencies that completed 500 or more FOIAs in 2020, the ATF had the fifth-longest processing time for requests designated as complex — about 16 months. Across the federal government, the number of FOIA requests backlogged was less than one-fifth the number of requests processed. For the ATF, it was nearly half.

Agencies like the Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement all outperform the ATF when it comes to completing public records requests.

The ATF’s lethargic response time has become so problematic that even ATF staff struggle to receive information from their own agency.

“They follow the policy of give nothing, and make the requester fight for it,” said Vincent Cefalu, a former ATF agent who was fired after his role in exposing the Fast and Furious gun-running scandal. Cefalu, who filed multiple FOIA requests as part of a lawsuit alleging retaliation by the ATF, said the lack of transparency drives a wedge between the agency and the public.

“It’s been a longstanding rule in law enforcement: We don’t work in the shadows, we work in the daylight,” Cefalu said. “It begs the question, ‘What are you hiding?’”

Other former ATF staff echoed Cefalu, saying that the agency’s secrecy breeds a poor workplace culture while simultaneously doing a disservice to the public.

“If the people who were the shady part of the ATF were exposed to a FOIA, and FOIA was actually doing its job, the shady part wouldn’t exist,” said Norm Bergeron, a former ATF agent who retired in 2017. Bergeron successfully sued the agency for information after he requested documents regarding why he was passed over for a promotion.

In his retirement, Bergeron assists current and former agents attempting to obtain public information from the ATF, often related to issues of retaliation and equal opportunity.

“We don’t need any new gun laws,” he said. “We need an agency that’s going to enforce them, and is transparent about their enforcement.”

Additional reporting by Nick Penzenstadler and Brian Freskos.