The House of Representatives voted Wednesday to pass the Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act of 2017, which would require all 50 states to recognize one another’s permits to carry concealed firearms, regardless of the gulfs that can exist between licensing standards.

The National Rifle Association has for a decade considered concealed-carry reciprocity as the top item on its federal legislative to-do list. The NRA and other proponents of the policy often compare it to driver’s licenses: If a license to drive issued by one state is valid in all American states and territories, why shouldn’t a license to carry a concealed gun be recognized just as widely?

The analogy quickly breaks down under scrutiny.

For one thing, governments and agencies voluntarily recognize driver’s licenses by joining an interstate compact, rather than submitting to a federal law mandating they do so.

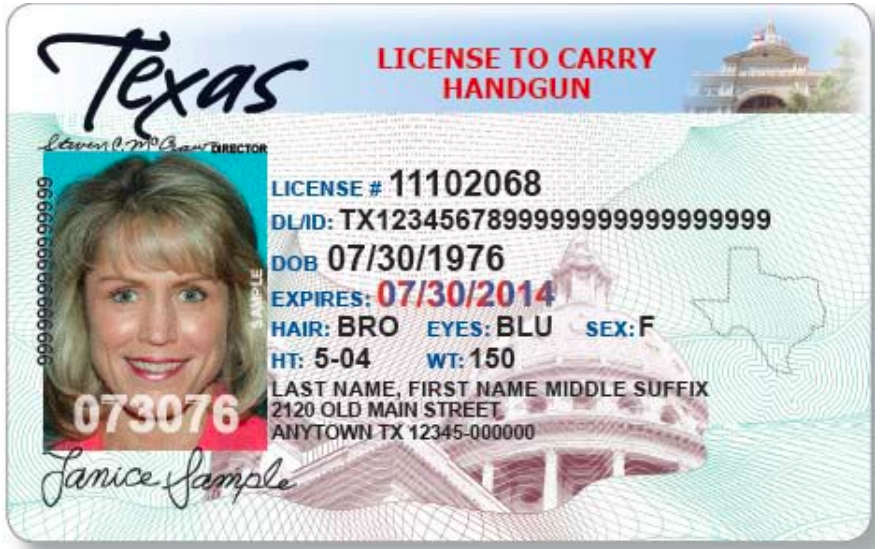

Crucially, states also agree to adopt basic security and recordkeeping practices when it comes to designing, issuing, and revoking driver’s licenses. The systems make it easier for police or other authorities to determine if a person’s license is valid during a traffic stop or other encounter. No such equivalent system exists for concealed-carry licenses, and the National Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act would not create one.

For decades, states have joined the Driver License Compact, which allows jurisdictions to pool data on motorists. That includes license suspensions and revocations, past violations and insurance status. A number of states also maintain searchable electronic records of car insurance policies, which are required to legally drive in all but three states.

Since the passage of the Real ID Act in 2005, the federal government has incentivized states to make sure physical licenses meet basic security standards and maintain certain uniform design features, including a digital photograph or machine-readable elements like a barcode, to satisfy airport security and other federal identification purposes.

None of this exists for licenses to carry concealed guns. There’s no single national, searchable repository of valid permits. The federal databases of criminal information that police rely upon, the National Crime Information Center and Interstate Identification Index, don’t indicate anything about whether someone is licensed to carry an unseen pistol in public.

What’s more, it’s rare for states or other local authorities to physically confiscate such licenses from people who have been convicted of a crime or are otherwise disqualified from going armed in public under their state’s rules.

States revoke or suspend thousands of concealed carry licenses every year.

In 2016, Texas revoked 982 licenses and suspended 1,623 more.

From July 1, 2016, through June 30, 2017, Florida revoked 1,492 licenses and suspended an additional 5,247.

As of December 4, Arizona had revoked 1,206 licenses and suspend 4,091.

Anthony Coulson is a retired Drug Enforcement Administration officer and consultant who manages the Arizona Criminal Justice Commission’s NICS Records Improvement Project. He says that when the state revokes or suspends a concealed carry license, it just sends a letter and trusts the gun owner to either surrender the permit or stop using it.

“That’s extremely problematic,” Coulson said, because the license holder could continue to use it anyway. Authorities in other states would have a hard time quickly determining the permit’s validity.

They might in fact feel deterred from even trying: The bill makes jurisdictions and police officers liable for legal damages if they detain a concealed carrier beyond a “brief investigative stop.”

Should that stop occur in the middle of the night, when the county or state office that issued the license is likely closed, an officer who wants to make sure a visitor is lawfully armed with the concealed pistol in his possession would have little choice but to ask to see that person’s permit, hope that it is legitimate, and send him on his way.