Over the course of her young life, Lakya Knight, an 18-year-old resident of West Pullman, a neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side, has lost several family members to gun violence. In 2008, when she was just 3, her father, Reginald Knight, was among those lost when a Chicago police officer shot and killed him. The city settled an excessive force lawsuit after his death for $100,000, but Lakya was still left with an empty space for the father she never got to know.

“It made it hard for me growing up, because I was always looking for that sense of security and stability,” Knight said. Years of asking questions has left her with the strong impression that her father had a big heart, loved music and sports, and was always protective over his family.

This year, Knight’s neighborhood has seen a dip in gun deaths. Through the end of July, West Pullman had six fewer deaths this year compared to the same period last year. Although these numbers mean that fewer lives are being lost to gun violence, community members say they still don’t feel safe and are grieving the seven people who were fatally shot this year. Residents like Knight want more to be done so they can freely enjoy their neighborhoods.

“It’s sad that sometimes when we walk up and down the street, we got to look over our shoulders to make sure we’re in an area that we’re safe, and that’s outside our communities or in our communities,” Knight said.

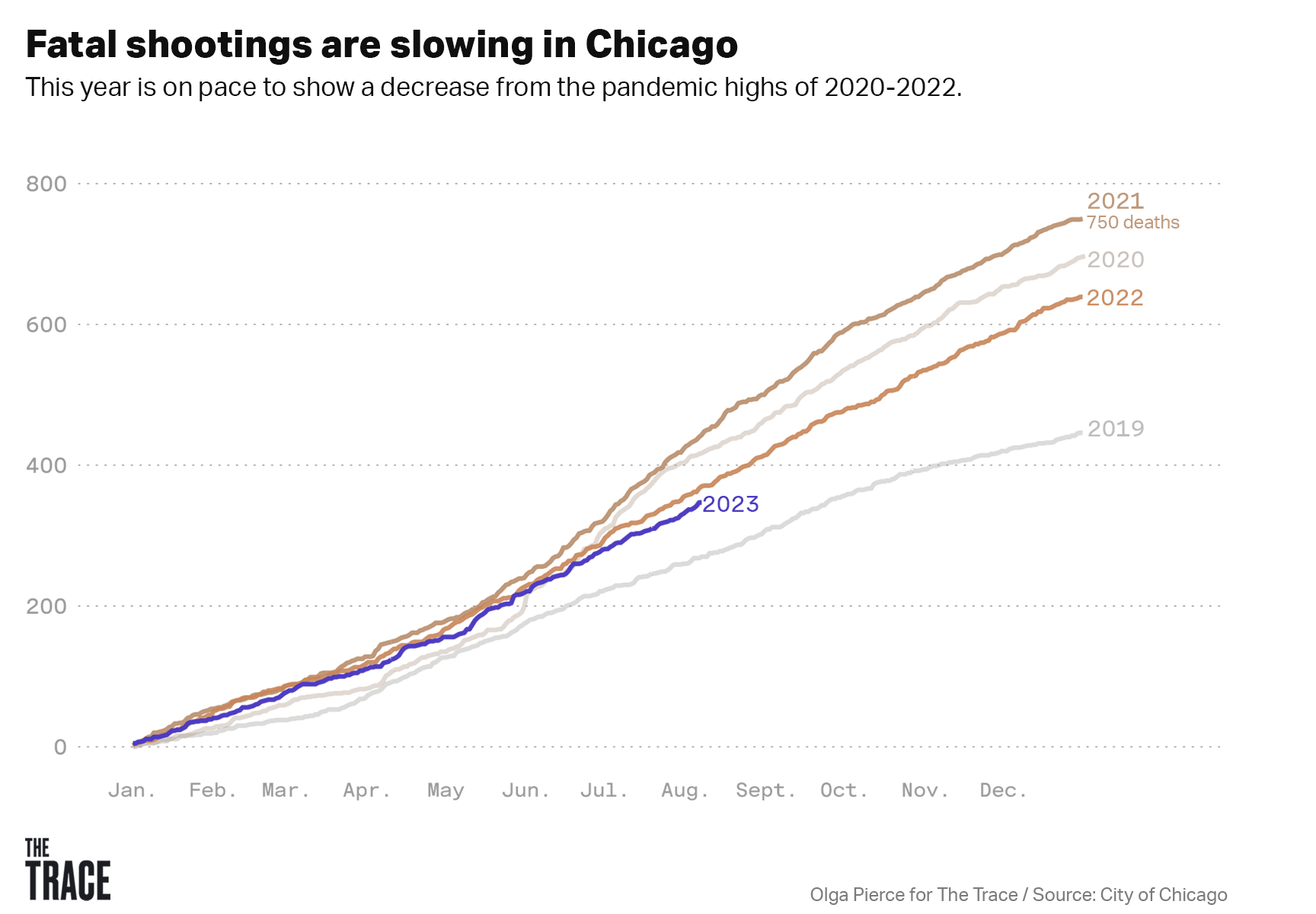

As is the case in West Pullman, gun homicides have steadily been falling in Chicago since 2022, according to data from the Chicago Police Department. This comes after a spike in gun deaths in 2020 and 2021, when the pandemic almost doubled the number of lives lost to 750. Despite the current trend, the data indicates that the rate of decline in fatal shootings has slowed down compared to 2022 and, if it continues apace, still won’t reach prepandemic levels by the end of this year.

In 2022, Chicago had 355 gun deaths by the end of July, a little over a 16 percent decrease from the same period in 2021. This year, the city has had 332 gun deaths, a decrease of 6.5 percent. Cities nationwide have experienced similar trends in the first half of 2023, with the 30 cities that made their data readily available in a new study reporting nearly 10 percent fewer homicides.

Chicago’s data shows that there continues to be a disparity in violence in the city’s South and West Side neighborhoods, which are primarily home to Black and Latino communities. Residents of these neighborhoods, which have borne the brunt of Chicago’s historic disinvestment in communities of color, have been outspoken about needing things like affordable housing, job training, and mental health facilities to help combat the long-term root causes of gun violence.

Leaders in violence prevention and intervention said that, while the numbers are not where they want them to be, they have seen success in their work by noticing a shift in the narrative about and effort around solving gun violence. They said it has changed from a niche problem addressed piecemeal by siloed organizations to a collective effort that includes government collaboration and investment. Mayor Brandon Johnson has promised to continue funding violence reduction efforts and tackle its root causes. Organizers said the city needs to continue listening to the hardest-hit communities.

“The lack of resources is what’s really killing the population,” Knight said. There have been a lot of recommendations on how to reduce gun violence, she added, but she hasn’t seen them put into action. She said she sometimes sees initiatives enacted, but that they’re inconsistent — and haven’t made a significant dent in the amount of gun violence.

Like the people in Knight’s neighborhood, Black and Latino residents are disproportionately affected, with Black Chicagoans comprising nearly 82 percent of the victims of gun homicides and Latinos making up about 15 percent in 2023. Male residents have consistently been killed the most, with almost 87 percent of fatal shootings victims being male this year.

“The last thing that is happening, which is the first thing we hear about in the news, is a person is shot and killed,” said Maggie Baczkowski, founder of Strides for Peace, a nonprofit that helps fund organizations that are fighting gun violence across the city. “But so much happened before to create that moment.” If organizations can change a few decisions along the way, she said, they may save a life.

In recent years, Illinois, Cook County, and Chicago have increased their investment in community violence reduction programs. Earlier this year, the Illinois Department of Human Services Office of Firearm Violence Prevention and Cook County’s Justice Advisory Council announced $25 million in grants to support residents at risk of experiencing gun violence in Chicago and suburban Cook County.

Violence prevention solutions must be tailored to community needs, said Gregorio Martinez, senior program manager of the city’s Community Safety Coordination Center. He said the city gets community input through its Leadership Collective, an advisory committee that convenes leaders from the city’s 15 most at-risk neighborhoods. Communicating with these leaders informs the city’s strategies and initiatives around gun violence, Martinez said, and helps them to know whether they’re on the right path.

“Violence prevention is one of those things that the city has to constantly keep an eye on,” Martinez said. Just like you must work to keep your body and mind healthy every day, he added, cities need to work regularly to keep communities healthy.

But gun violence is unpredictable, and funding or policy inconsistencies don’t always explain why a community like Austin on the city’s West Side — which has received a lot of violence reduction funding — has five more gun deaths this year than last, or why a community like Chatham on the South Side has experienced more than twice as many gun homicides this year, when numbers seemed to be decreasing in 2022.

JaShawn Hill, executive director of Chicago Survivors, an organization that provides services to survivors of gun violence, said many Chicagoans are still experiencing the aftereffects of being isolated during the pandemic.

“A lot of people were dysregulated,” Hill said. “I think we set those survivors up for failure.” She said that, without continued trauma care and support, people affected by gun violence aren’t able to establish resiliency and interrupt cycles of violence. Hill added that young people were some of those affected the most, when they were not able to return to school and access that channel of support.

Without activities to keep them busy, Knight said, young people can get swept up in gun violence — as victims or perpetrators. Youth make up almost half of the victims of gun violence. Kids and teens through age 19 make up 17.5 percent of victims. Young adults ages 20 through 29 make up a little over 30 percent.

Although Johnson’s transition team recently released its recommendations for addressing public safety, it hasn’t shared tangible plans for reducing gun violence. But Martinez, who’s been doing violence reduction work for five years, said he is excited about the way the administration is talking about tackling violence through a holistic approach.

“Yes, law enforcement is part of that strategy,” Martinez said. “But we also understand that if we’re really trying to address the root causes of violence, we have to make sure we address those factors.” He said that basic needs like employment, education, housing, and food security must be met in order for violence prevention solutions to be effective.

Despite the hardships, communities facing violence are still full of life, Martinez said. “These are really vibrant, beautiful communities filled with beautiful people with beautiful cultures.”