The National Rifle Association and its former public relations partner Ackerman McQueen spent years in court trading accusations of libel, fraud, and breach of contract. As the parties brawled, they were forced to expose much of their inner workings, which makes it particularly strange that the adversaries are now involved in a lawsuit that is being carried out entirely in secret.

Not even an index number for the case, underway in a Texas federal court, appears in a database of federal court actions. While individual documents are commonly sealed in civil cases, it’s extremely unusual to shield the very existence of a case from the public. The step can only be taken as a “last resort,” according to federal court policy, and “justified by a showing of extraordinary circumstances and the absence of narrower feasible and effective alternatives.”

Jane Kirtley, director of the Silha Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law at the University of Minnesota, said that courts have generally sealed entire cases for the same reasons that a particular filing is made confidential: to protect personal privacy, national security, or trade secrets. Simply wanting to avoid attention is not a valid basis, she said. “People that have disputes don’t have to use courts to settle them, they have other options,” Kirtley said. “The price of admission ought to be that the filing of a lawsuit is a matter of public record, and that if elements of a case are sealed, it’s only for legitimate reasons.”

In 2019, a rift between the NRA and Ackerman erupted in dueling suits alleging deceit and betrayal. The feud fed tumult that has plagued the NRA in recent years and sapped its clout. The parties reached a confidential settlement in March 2022. As The Trace reported in April, a witness report filed in New York Attorney General Letitia James’s suit against the gun group states that the case ended “with the NRA paying Ackerman $12 million in settlement funds.”

At some point last year, presumably after that settlement was reached, the NRA filed this secret suit against Ackerman and one of its subsidiaries, The Mercury Group. Judge A. Joe Fish, who oversaw the settled case, is also handling the sealed proceeding, records suggest. Federal court policy calls on judges to justify the sealing of an entire civil case with a written order that explains the decision. The Trace got no response to messages left at Fish’s chambers asking for such an order or, in the alternative, to simply unseal the case. Written questions were sent to the chief clerk of the district. In response, the district’s deputy of operations said in an email that court employees “are prohibited from commenting on the status of any case that is filed under seal, which includes confirming that any such sealed case exists.”

Although judges are not supposed to seal cases merely because the parties would prefer anonymity, Kirtley said that too often they do. “Judges concentrate on the parties before them,” Kirtley said, “and if the parties are content with or agitating for secrecy, some courts don’t care and just go along to get along. But that ignores the fact that the public has an interest in open courts, in how cases proceed, in whether one party gets a break and another does not.”

The parties did not respond to written questions and requests for comment.

The Trace learned of the case because the NRA attempted to subpoena the wife of Tony Makris, the head of The Mercury Group and until the relationship imploded, a longtime confidante of the gun group’s CEO, Wayne LaPierre. In June, Makris’s wife filed a motion to quash the subpoena in another federal court district that refers to the sealed case in Texas. She states in the motion that she handed over much of the information sought in prior litigation.

“Goddamn, that is crazy,” former NRA board member Phil Journey, whose term expired in April, said when told about the sealed case, which was filed by the Dallas-based firm of the group’s outside counsel, William A. Brewer III. Journey, a dissident voice while on the board, said that it’s been “difficult to divine” Brewer’s strategy for the NRA, which plans to move its headquarters from Virginia to Texas. “It’s hard to be candid, other than to say if the facts aren’t on your side, you turn to the law, and if the law is not on your side, you baffle them with BS,” Journey said.

Brewer’s sizable legal fees contributed to internal furor at the NRA that prompted a leadership upheaval four years ago. He is married to the daughter of Angus McQueen, Ackerman McQueen’s longtime chief executive who died in 2019. Brewer initiated the NRA’s litigation against his father-in-law’s company and Ackerman attorneys have alleged that his motivations were personal. Critics of NRA leadership have charged that Brewer’s strategy is designed to protect LaPierre rather than the organization. The Trace has detailed how Brewer’s legal exploits have cost the NRA huge sums and led to few courtroom victories.

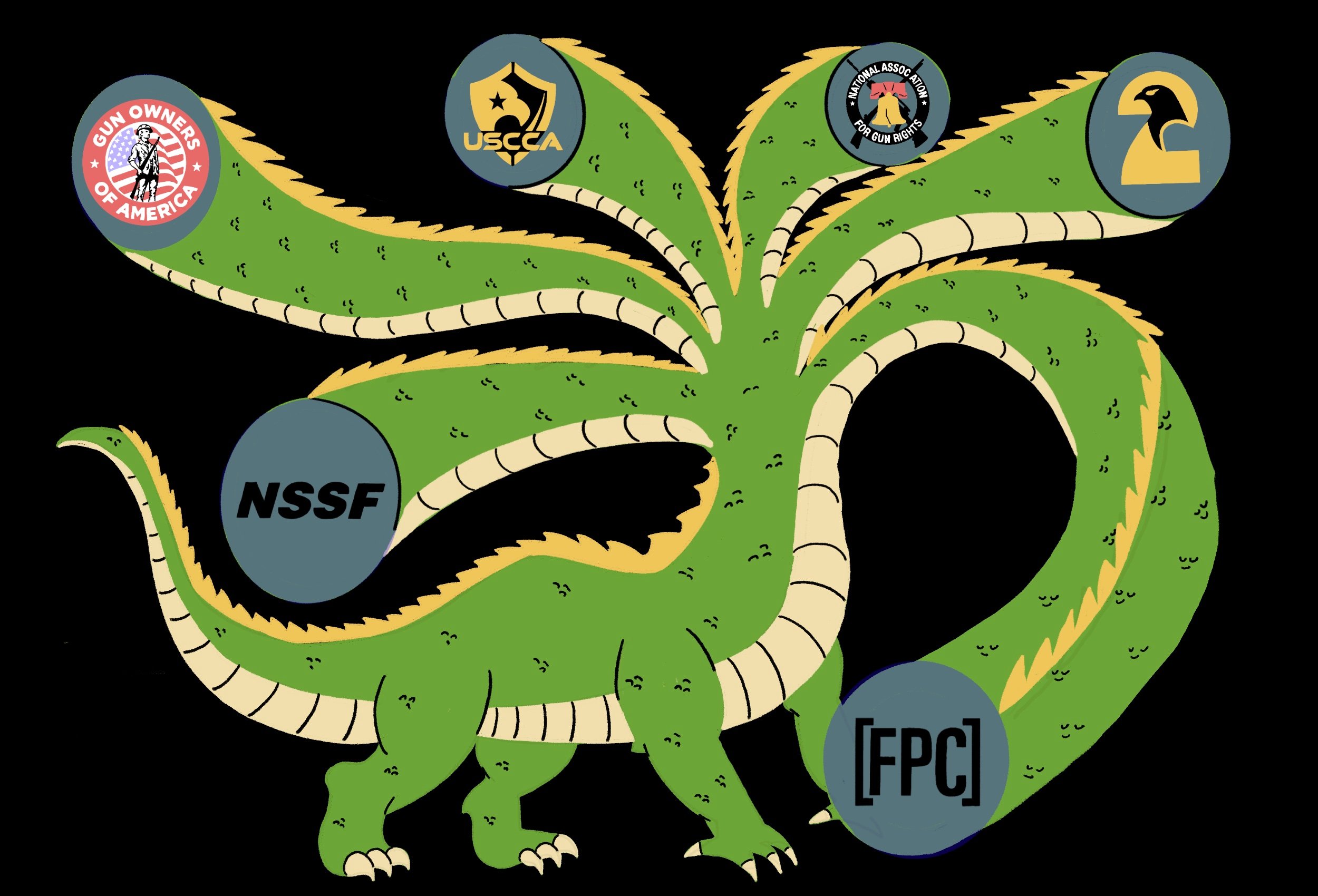

That focus on legal disputes not directly tied to gun rights has added to a sense among many gun advocates that the NRA is distracted, enfeebled, and no longer the standard bearer for their cause. Several gun groups recently won injunctions that shielded their members from a new rule by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives on stabilizing braces, an accessory for AR-15 style pistols. A judge rejected the NRA’s attempt to join the litigation and win the same protection for its members, finding that the group’s request came too late and that its interests were adequately protected by the other gun rights organizations involved in the case. The slap down prompted jeers from some corners of the gun rights community, and the NRA scrambled to bring its own action against the ATF.

The NRA’s exploding legal costs come at a time when membership, a primary source of cash for the gun group, is shrinking, and significant litigation spending is ahead. Journey said the New York State Attorney General’s Office recently contacted him to schedule his testimony in its case against the NRA, which it expects will go to trial in October and last six to eight weeks.

Mike Spies contributed to this reporting.