On April 28, a man opened fire on his neighbors in Cleveland, Texas, killing five of them. He had reportedly become enraged after they asked if he could stop firing guns on his property. It was late, they explained, and a baby was trying to sleep.

“He had been drinking, and he said ‘I’ll do what I want to in my backyard,’” the sheriff said.

The Cleveland gunman is one of at least 30 mass shooters since 1966 who have had problems with alcohol misuse, according to The Violence Project, a nonprofit that tracks a narrowly defined subset of mass gun attacks: those that occur in public places, take four or more lives, and have no connection to any underlying criminal activity.

Alcohol is implicated in everyday shootings, too. An estimated one in three gun homicide perpetrators drank heavily before killing their victims, according to a recent report from Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions and the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy. It’s worth noting that the same proportion of gun homicide victims drank heavily before being killed, as did a quarter of gun suicide victims.

But despite a preponderance of evidence, regulation around the intersection of guns and alcohol is a patchwork that depends on inconsistent definitions of alcohol abuse. Also, passing stronger policies meant to address the relationship between alcohol and gun violence has never been a primary focus of gun reform efforts.

“We realized that gun violence and alcohol use were leading causes of injury and death in the United States,” said Silvia Villarreal, the lead author of the Hopkins report. “Alcohol kills 140,000 people annually, and gun violence killed more than 48,000 people [in 2021]. So these issues alone are big problems. But when they’re combined, it’s when they are most deadly.”

Here, we examine the intersection of alcohol and guns.

What are the dangers of mixing alcohol and guns?

Research has shown that alcohol misuse increases the risk of gun assault, homicide, and suicide. That’s because alcohol lowers inhibitions and impairs judgment, making bad decisions seems like a good idea — like reaching for a gun during an argument or a mental health crisis, or unsafely carrying or storing a firearm. A 2021 study found that alcohol misuse was associated with unsafe gun storage in households with children.

Also, alcohol misuse can be a harbinger of future violence. In 2017, researchers from the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California, Davis, found that legal gun owners who’ve been convicted of an alcohol-related offense — like driving under the influence or drunk and disorderly conduct — are up to five times as likely to be arrested for a violent or gun-related crime.

“At the individual level, the data is really clear that denying high-risk individuals access to firearms reduces their subsequent risk for violence,” said Garen Wintemute, director of UC Davis’s Violence Prevention Research Program who has published a number of pioneering studies on the link between alcohol and gun violence.

What kind of laws regulate guns and alcohol use?

Federal law prohibits someone from buying a gun if they are “an unlawful user of, or addicted to, marijuana or any depressant, stimulant, narcotic drug, or any other controlled substance.” But alcohol is excluded from the federal definition of depressant and is not considered a controlled substance. As a result, regulating alcohol consumption and gun ownership is left entirely to the states.

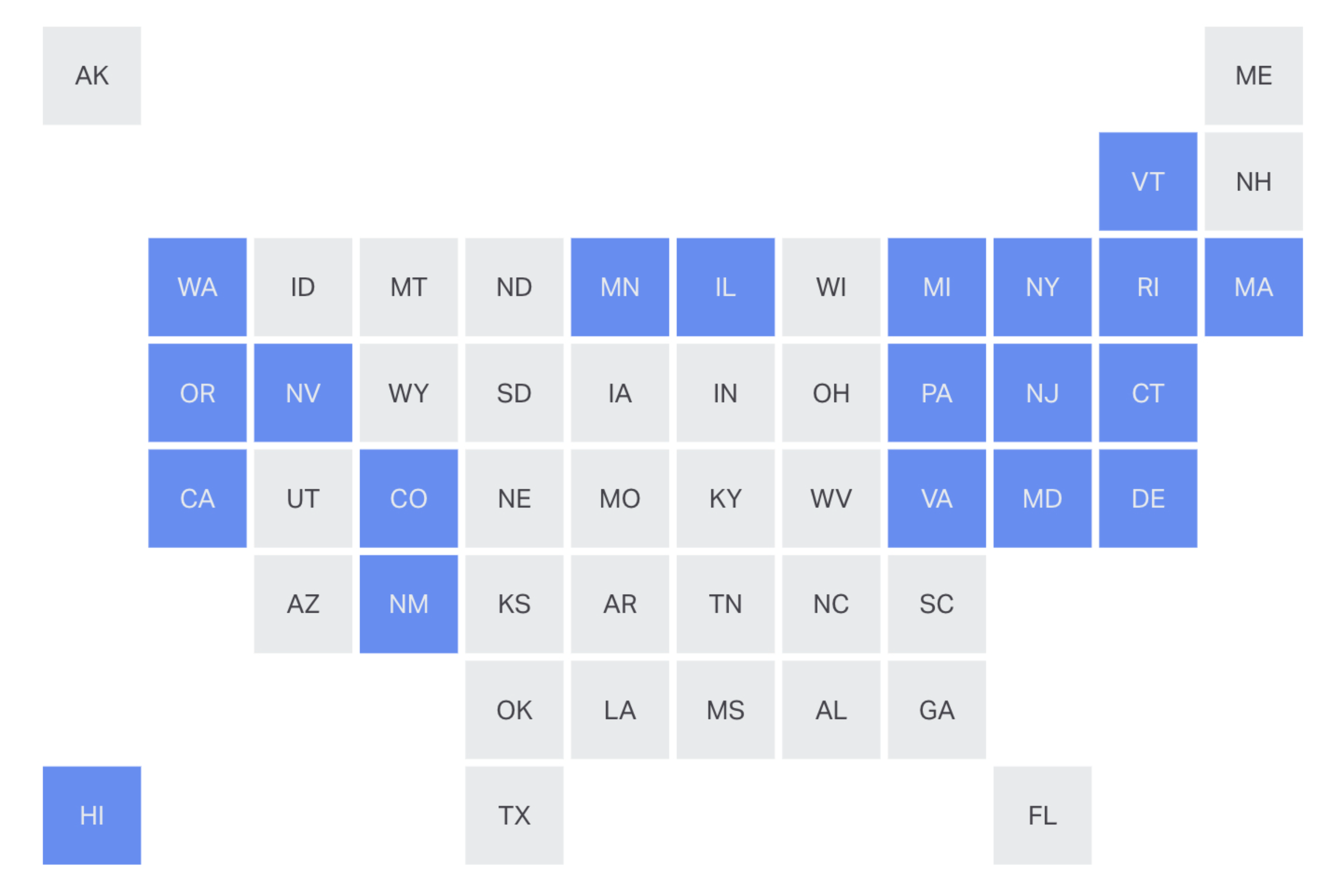

State-level prohibitions generally relate to four categories of behavior: the possession and carrying of guns; the issuance of permits to purchase or carry guns; gun sales; and carrying guns in places that serve or sell alcohol.

- Thirty-four states ban the possession or carrying of some or all firearms on the basis of alcohol abuse or active intoxication, according to a Trace review of state gun policies.

- Nineteen states and Washington, D.C., prohibit gun sales to people who have a history of alcohol misuse or who are actively intoxicated.

- Thirty states and D.C. disqualify people who have misused alcohol from obtaining permits to own or carry guns (Though 18 of those 30 states do not require permits.)

- Twenty-four states and D.C. prohibit guns in places where alcohol is served or consumed, whether it’s a restaurant, a bar, or other such establishment.

Explore State Laws Related to Alcohol and Firearms

State laws related to firearms and alcohol vary widely. Below you can explore how being actively intoxicated can affect a person’s ability to legally carry or buy guns in the moment, how a history of chronic misuse of alcohol affects one’s ability to get a carry permit, how states use place-based regulations to restrict guns at venues like bars, and how states allow a record of alcohol misuse to be considered in the issuance of red flag orders.

That’s a lot of different regulations. But the criteria for when a person’s alcohol use triggers a prohibition varies dramatically from state to state, ranging from involuntary commitment on the basis of alcohol abuse to being a “habitual drunkard,” a medically imprecise term that isn’t always defined in state statutes, or being “addicted to” or “chemically dependent” on alcohol. Some states define those terms by DUI convictions, a minimum blood alcohol level, severe impairment or incapacitation — or not at all.

For instance, Alabama, Florida, Missouri, South Carolina, and West Virginia ban the possession or carrying of handguns for someone who is a “habitual drunkard,” “chronic alcoholic,” or “addicted to alcohol,” but does not say how that’s determined. Illinois, Iowa, and Maryland go one step further, defining “habitual drunkard” and “intoxicated” as someone who’s had a DUI. Michigan, Nevada, and Utah define “intoxicated” or “under the influence” as someone with a certain blood alcohol content. And that’s just for prohibitions on possession and carrying — each of those states has a different standard for alcohol misuse when it comes to prohibitions on gun sales and the issuance of concealed carry permits.

That ambiguity and inconsistency make such regulations difficult to enforce, researchers said.

Which laws are the most effective?

Wintemute, of UC Davis, said alcohol-related criminal convictions, particularly DUIs, provide a “quantifiable measure of alcohol misuse.” “Firearm owners who have DUIs, even just one, are at substantially increased risk for committing violent crime and committing firearm-related crime,” he said.

“It’s possible that alcohol use is associated with, and actually facilitates, aggression directly,” said Rose Kagawa, an assistant professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of California, Davis, who has authored several studies on the intersection of alcohol and guns. “A DUI can be an indicator more generally of a greater willingness to engage in dangerous or harmful behaviors.”

Every state and Washington, D.C., has a gun ban that kicks in when someone gets a certain number of DUIs, according to the Johns Hopkins report. The thresholds vary, as do the lengths of the bans. In 21 states, a ban kicks in with four DUIs; in 24 states, it’s three DUIs; in four states, it’s two. Depending on the state, a ban can last for five years, a decade, or a lifetime.

The Johns Hopkins researchers recommend a five-year gun ban for people convicted of two or more DUIs in a five-year period. Around 90 percent of people arrested at least twice for a DUI meet the clinical definition for alcohol dependence or misuse, they said. Setting two DUIs as a threshold would clarify who exactly qualifies for alcohol-related gun bans, with less reliance on insensitive and imprecise terms like “habitual drunkard.”

Wintemute summed up the logic behind DUI-based bans: “If you can’t control yourself behind the wheel, maybe you can’t control yourself behind the trigger, either.”

The Johns Hopkins researchers also recommend adopting laws that prohibit the issuance of a concealed carry license to anyone with a court record of alcohol misuse within the past five years, including DUIs that result in plea deals, involuntary commitment to a treatment facility, and convictions for public intoxication or drunk and disorderly conduct.

They also said states should adopt laws that allow judges to take alcohol misuse into account when considering red flag petitions and issuing domestic violence restraining orders. Right now, 16 of the 21 states that have enacted red flag laws explicitly list alcohol misuse as a factor that judges can consider.

Are there any drawbacks to these laws?

Research has shown that DUI enforcement is racially biased. A 2021 paper co-authored by Kagawa and Wintemute found that Hispanic or Latino men were up to 66 percent more likely than white men to be convicted of a DUI in California over a 15-year period. That’s indicative of racial bias at traffic stops, which is how most people interact with police. Black drivers are more likely to be stopped and searched, Kagawa said, and DUI checkpoints are disproportionately located in neighborhoods of color. So any regulations that involve law enforcement will disproportionately impact racially marginalized groups.

That’s something Villarreal said she and her co-authors grappled with, and the solution isn’t simple. “We know that the criminal legal system often results in inequitable enforcement and people of color are disproportionately arrested and convicted with longer sentences,” Villarreal said. “So what we did is explore how we could implement these policies in a more equitable way.”

One way is by implementing objective, quantifiable criteria for alcohol-related gun prohibitions, like blood alcohol content, rather than stigmatizing terms that are open to interpretation and abuse, the researchers said. They also urged implicit bias and de-escalation training for officers, as well as increased supervisory oversight, and said law enforcement should record and document the justification for traffic stops.

Advocates and researchers say policy in this area should be carefully tailored so as not to discourage people from seeking alcohol abuse treatment.

Are there currently efforts to pass laws regulating alcohol and guns?

In the last few years, lawmakers and gun reform groups have begun to look more closely at the connection between alcohol and gun violence. Wintemute said that’s partly due to the newness of some of the research, but also because the focus has been on policies that remain stymied, including universal background checks and assault weapon bans.

“Our country has been missing the forest for the trees,” said Megan Ranney, a professor of emergency medicine at Brown University and co-founder of the gun violence research group AFFIRM. “Over and over again, studies have shown that people who misuse alcohol are more likely to shoot themselves and others. It’s time for us to start talking about the dangers of drinking and shooting, just like we talk about the dangers of drinking and driving.”

Is there public support for these laws?

While a federal gun ban for alcohol abusers “hasn’t been the focus of the policy groups,” Wintemute said, “support for an alcohol-based restriction is pretty high, not just in the general population but among firearm owners.” A 2020 survey commissioned by Wintemute and his team found that 50 percent of California gun owners and 67 of residents who live with gun owners support a five-year ban on gun possession for people with two or more DUIs.