“If it bleeds it leads,” I thought as my professor barricaded me and 20 other students in her office; an armed man was running around our college town’s sewage system, and we were locking down. Emergency alert texts from Indiana University warned that he could emerge from the storm drain by the building we were in.

It’s an unsavory fundamental of journalism: You run toward the bloodshed while everyone else tries to escape it. As a young journalist, I’ve reported consistently on gun violence. But now, it was my turn to hide.

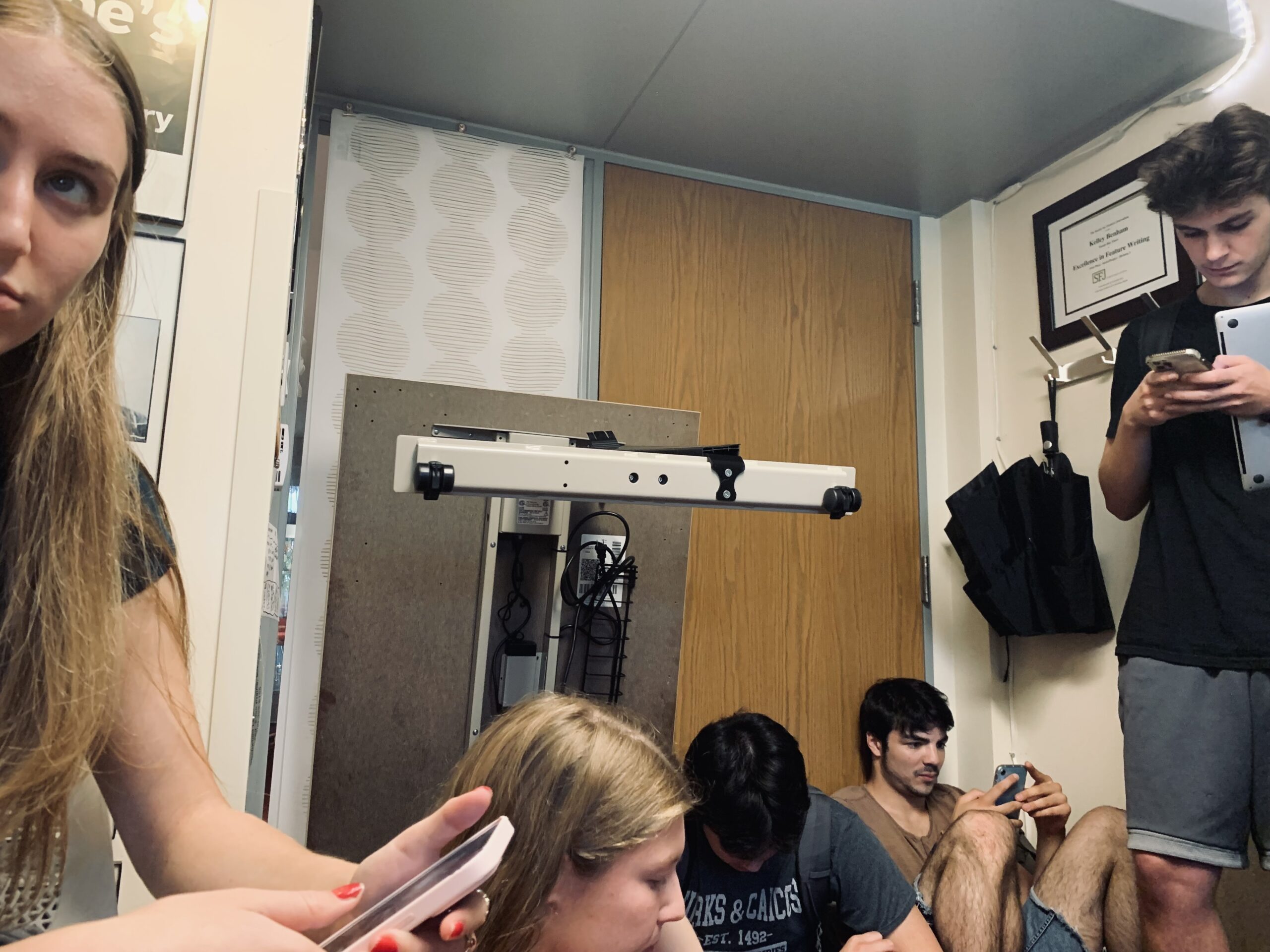

The air was warm, almost sticky from our collective breath. Every head was down, sending or receiving updates, scouring social media for tidbits of information, anything about this potential shooter’s location. At one point, a photo of a man on Snapchat holding a large gun stirred the room. Only later did we find out he was a member of law enforcement, not the barefoot, half-naked suspect in the sewer. But in that moment, we knew nothing except Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland, Uvalde. These shootings follow a script, and Bloomington, Indiana, might have been the next line in the never-ending story of American carnage.

I was 20 years old when I covered my first mass shooting as a freelancer for The Washington Post. The year before, I left a murder scene with a shooting victim’s blood on my shoes (my mom, to no avail, tried to wash off the stains). And before that, at 18, my first journalism byline was for The Trace’s national reporting project, “Since Parkland.”

The project was led by student journalists from around the country who wrote nearly 1,200 obituaries for every American child and teenager shot and killed from 2018 to 2019. Week after week, a grim cycle revealed itself: A young person alive on Monday would be dead by Friday’s deadline. We told the stories of victims forgotten after the 24/7 news cycle, focusing on who they were in life, not just how they died.

By phone, I interviewed family members of the dead from my high school library. In September of senior year, my third-period class emptied as classmates attended the funeral of a brother and sister shot by their father in a murder-suicide one town over. My stomach dropped when I read their names on my weekly assignment spreadsheet.

I had 100 words to capture their lives:

He was known for playing practical jokes and being mischievous with family. A friend who enjoyed his laughter cited him as an inspiration, a “loving and compassionate human being.”

He loved fishing, reading, and, most of all, tennis. He adored playing for Zionsville High School, especially because of the camaraderie he had with teammates.

On Sept. 21, 2018, Harrison Fredric Hunn, 15, along with his sister Shelby Hunn, was shot in his sleep by his father in Zionsville, Indiana. The same week as his funeral, his tennis teammates dedicated the sectional title win to his honor.

That work — their names — flashed before me as I sat on the floor of my professor’s office, enduring the long minutes of lockdown. “If the worst happens,” I thought, “who will write my obituary?”

We were evacuated from the building an hour or so later. But the adrenaline didn’t wear off until the next day. I woke up feeling like I had just been swimming in the ocean, clobbered by waves. I was sore from yesterday’s fears.

In the end, as my professor wrote in USA TODAY, our lockdown wasn’t particularly newsworthy. Though the armed man threatened police with a gun, no shots were fired. No one died. After the suspect was apprehended, officers found a machete, scythe, and rifle cartridges in the sewer, but no gun. Still, lives were interrupted. Dark imaginations — or memories — were activated as an entire town feared the worst. And in the fortunate absence of death, a complicated trauma set in.

I know from my work and this helpless experience that we need reporting that captures the various effects of gun violence, particularly on this generation, which grew up with more school shootings and lockdown drills than any generation before. When the carnage can be seen, we’re more willing to witness the reverberations; we want to know how the story ends. But what about the living? Who is accounting for the injured, the survivors, the young people who live with the knowledge that their lives can be threatened by gun violence at any moment? Who keeps track of the “lucky” ones?

As a reporter, I’m accustomed to not having an answer. But I do know one thing: This is a compounding, expanding, borderless pattern. Last month, it was my school. This month, it will be someone else’s.