Under pressure from Congressional Republicans, federal regulators abruptly abandoned an apparent effort to restrict a firearms accessory that was implicated months later in the mass shooting of 10 people at a Boulder, Colorado, supermarket.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives issued a notice on December 18 seeking public comments on criteria it had developed for evaluating whether firearms outfitted with so-called stabilizing braces would be subject to tougher federal rules. Stabilizing braces are popular accessories intended to increase the accuracy of AR-15-style pistols and allow users to fire them much like their rifle counterparts. Americans have bought millions of stabilizing braces since ATF approved their sale nearly a decade ago.

Many gun industry insiders saw December’s notice as a sign that ATF intended to impose screening and registration requirements on brace-equipped pistols, potentially forcing prospective buyers to wait several months before taking one of the weapons home.

But the ATF rescinded the notice five days later after 90 Republican House lawmakers sent the bureau a letter criticizing the proposed criteria as “ambiguous and malleable.” The letter, spearheaded by Representative Richard Hudson of North Carolina, also lambasted the ATF for seeming intent on “banning stabilizing braces outright and submitting lawfully purchased firearms and their owners to federal regulation.”

The ATF’s unwillingness to crack down on stabilizing braces has generated renewed scrutiny following the March 22 mass shooting of 10 people at the King Soopers grocery store in Boulder. Authorities have said the gunman was armed with a Ruger AR-556 pistol that he purchased six days before the attack. The pistol comes with a stabilizing brace already installed.

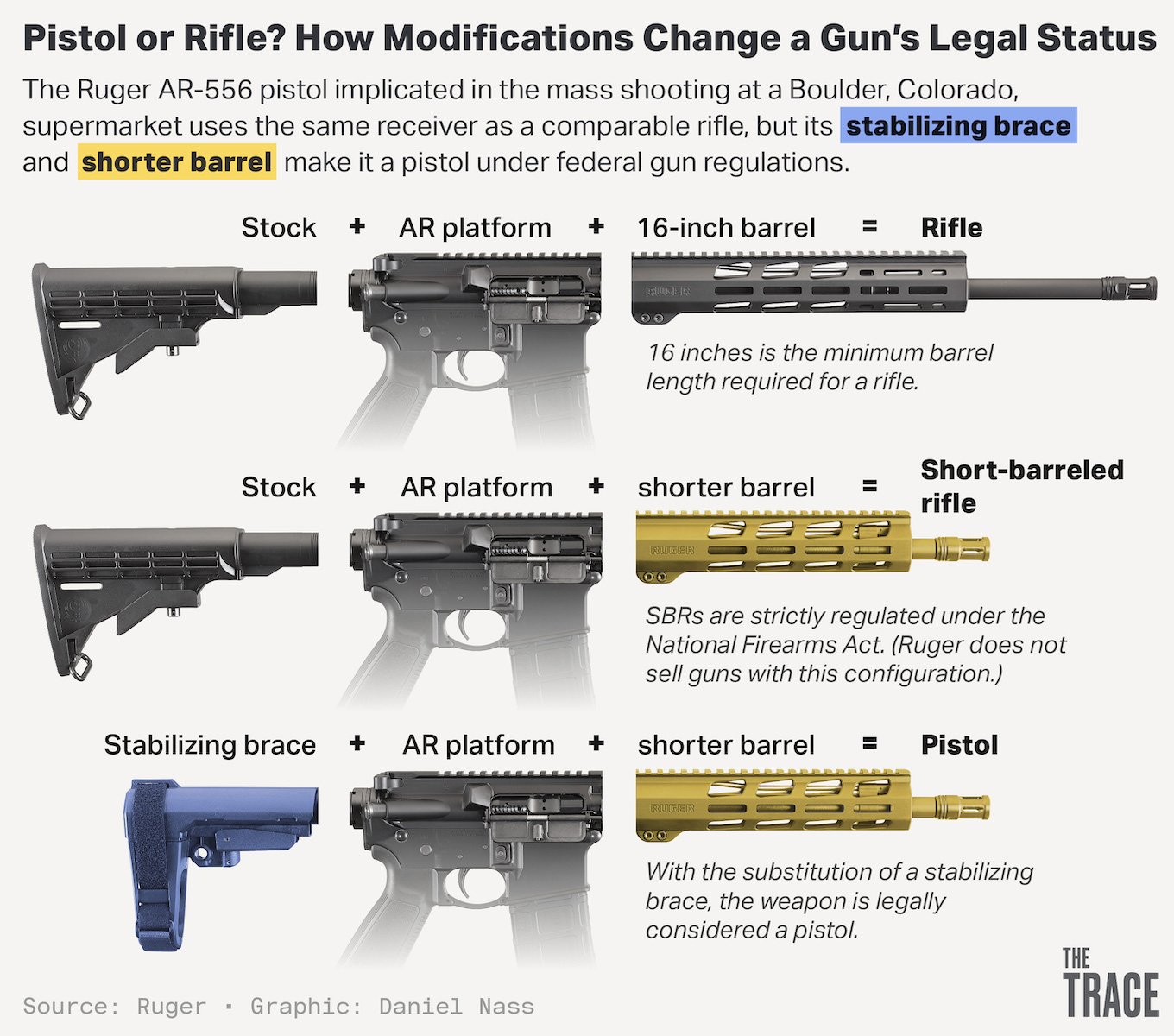

The AR-style pistol is incredibly close in design and functionality to one of the most highly regulated types of firearms available in the U.S., the short-barreled rifle. Under the National Firearms Act, a person buying a rifle with a barrel shorter than 16 inches in length has to pay a $200 tax and is subject to a lengthy application and vetting process. Short-barreled rifles are also one of the few types of firearms that owners have to register with the federal government.

Even though AR-style pistols appear nearly identical to a short-barreled AR-15, the ATF has officially classified them as handguns because they were made to be fired with one hand, sparing their owners from NFA controls. A crucial factor in the bureau’s decision was the AR-style pistol’s lack of a stock, the component that allows rifles to be fired while held against the shooter’s shoulder, improving control and accuracy.

AR-style pistols have been on the market for years but were unappealing to most gun owners because they were costly and unwieldy. Then the ATF in 2012 approved outfitting those products with a stabilizing brace, sending their popularity soaring. While companies have billed stabilizing braces as a means to steady AR-style pistols during one-handed fire, it’s an open secret in the gun world that the braces function much like a rifle stock.

In a 2017 article for Firearm News magazine, writer James Tarr noted how shooters had “quickly discovered that using one of these braces in a manner not intended by the designer suddenly turned awkward AR-15 pistols into ersatz SBRs (short-barreled rifles) both in appearance and functionality.” Tarr added that AR-15 pistols were “easier and cheaper to obtain” and didn’t necessitate filing “special paperwork to transport them across state lines.”

The introduction of stabilizing braces has opened a new frontier for gun companies seeking to sell customers on the idea of rifle-caliber power in a compact, lightweight form. Braces are now made not only for AR-style pistols but also pistols based on AKs and other semi-automatic rifle receivers.

Boulder marked at least the second high-profile mass shooting involving a stabilizing brace in as many years. The gunman who shot and killed nine people outside a Dayton, Ohio, bar in August 2019 used a AR-type pistol outfitted with a brace and a double-drum magazine capable of holding 100 rounds of ammunition. AR-style pistols with braces have also surfaced in the hands of drug traffickers and neo-nazi groups.

The use of the accessories in crimes has led former ATF officials to question why the bureau has not stepped in to bring stabilizing braces under stronger controls.

“I can’t even imagine to guess what was in their minds,” when the bureau decided to exempt brace-equipped pistols from the NFA, said Joseph Vince, a former ATF agent who headed the bureau’s Crime Gun Analysis Branch before retiring in 1999.

Vince, now a professor at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland, attributed part of the problem to the ambiguous nature of federal gun laws, which have made it difficult for the ATF to assert its authority over the objections of critics. “We’re dealing with mid-20th century law to cover 21st century technology,” Vince said. “It’s just so outdated in so many areas — and nobody wants to do anything about it.”

The ATF said in an email that the bureau “routinely reviews our practices, procedures, and determinations” but could not “comment on internal communications or deliberations on potential or hypothetical rulemakings.” A spokesperson for Representative Hudson declined to comment, saying the lawmaker was waiting until the Boulder investigation was completed “and we know all the facts first.”

The person credited with inventing the stabilizing brace, Alex Bosco, reportedly pursued his idea to help wounded veterans and other people with disabilities shoot AR-style pistols safely. The braces typically attach to the rear of the weapon and strap to the shooter’s forearm, allowing the shooter to fire the weapon one-handed.

But the fact that the braces also allow users to fire their AR-style pistols in much the same way as a rifle undermines the NFA, originally enacted to curb the availability of small arms that the government had deemed particularly dangerous or effective in the hands of criminals.

Congress passed the NFA in 1934 seeking to clamp down on Thompson submachine guns and other weapons frequently involved in organized crime and bank robberies. It applies to fully automatic weapons, suppressors, and sawed-off shotguns. The NFA is widely considered one of the most effective gun-control measures in history because the use of those weapons in crime dropped precipitously after its passage and remains rare today. Violations of the NFA can result in a $10,000 fine and up to 10 years in prison.

A decision by ATF to subject stabilizing braces to the NFA would undoubtedly spark a court challenge. On March 25, a federal appellate court halted the ATF’s ban on bump stocks, an accessory that increases the rate of fire for semiautomatic weapons. The bureau had long held that it lacked the authority to regulate bump stocks but reversed its position following the 2017 mass shooting in Las Vegas, where a gunman used the devices to kill 58 people.

Contact Us

Learn how to contact our reporters securely.

Bosco’s stabilizing brace is credited with rejuvenating the moribund market for AR-style pistols. Buyers of such pistols realized they could own what was akin to a more maneuverable, easily concealable tactical rifle while bypassing the added effort and expense that came with owning a weapon covered by the NFA. Ballistic Magazine once reported that the stabilizing brace made “those of us who might have dumped two C-notes on the paper to register a short-barreled rifle look awfully stupid.”

Mark Jones, a former ATF agent who held various supervisory positions before retiring in 2011, told The Trace that the bureau’s reluctance to classify brace-equipped pistols under the NFA reflected a “laissez-faire attitude” about the firearms industry that became prevalent under the Trump administration.

“ATF puts so few resources toward the regulatory side anymore, and it’s been that way for a while now because they’re terrified of being criticized by the firearms industry,” Jones said. “This is a short-barreled rifle that isn’t classified as a short-barreled rifle, and these now-ubiquitous things have been in at least two mass shootings.”

In 2012, Bosco’s company, SB Tactical, won approval from the ATF to begin selling stabilizing braces free from NFA restrictions. The company signed a distribution agreement with Sig Sauer the following year, and SB Tactical stabilizing braces hit the market a few months later.

The ATF ruling shocked former bureau officials as a sharp departure from decades of thinking on what constitutes a short-barreled rifle under the NFA.

“They’re selling by the millions, if not more,” said Rick Vasquez, a former head of the ATF’s Firearms and Ammunition Technology Division, the branch of ATF that oversees NFA-regulated firearms and the classification of new firearm products entering the market. “In 2012, ATF decided to overturn 31 years of policy of denying arm braces, and they did it on behalf of SB Tactical.”

Other companies have since swooped in with their own lines of stabilizing braces, and sales have far exceeded the number of customers that would be expected if buyers were truly limited to people with disabilities, critics say.

The Ruger AR-556 purchased by the Boulder gunman comes standard with a brace made by SB Tactical. The company did not respond for requests to comment. According to quarterly sales figures, Ruger’s AR-556 pistol, along with its four latest additional pistol offerings, netted the company $111 million last year, accounting for 22 percent of the company’s sales.

In more recent years, the ATF has issued a series of contradictory opinions on whether adding a brace to a pistol brings the weapon under the NFA, injecting uncertainty into the market, much to the chagrin of gun companies.

The bureau said in an open letter published in 2015 that using a brace as a shoulder stock would constitute a “redesign” and trigger the NFA. But after President Trump won the White House, the second-highest ranking official at the ATF, Ronald Turk, circulated a white paper saying that the bureau’s 2015 opinion had caused “confusion and concern” within the gun industry. To mitigate this, Turk said, the ATF could remove the language on how using a brace as a stock constituted a redesign.

According to records obtained via the Freedom of Information Act by the gun control group Brady, Turk authored his white paper with assistance from an attorney for SB Tactical. A few months later, the ATF sent a letter to SB Tactical reversing the bureau’s 2015 opinion.