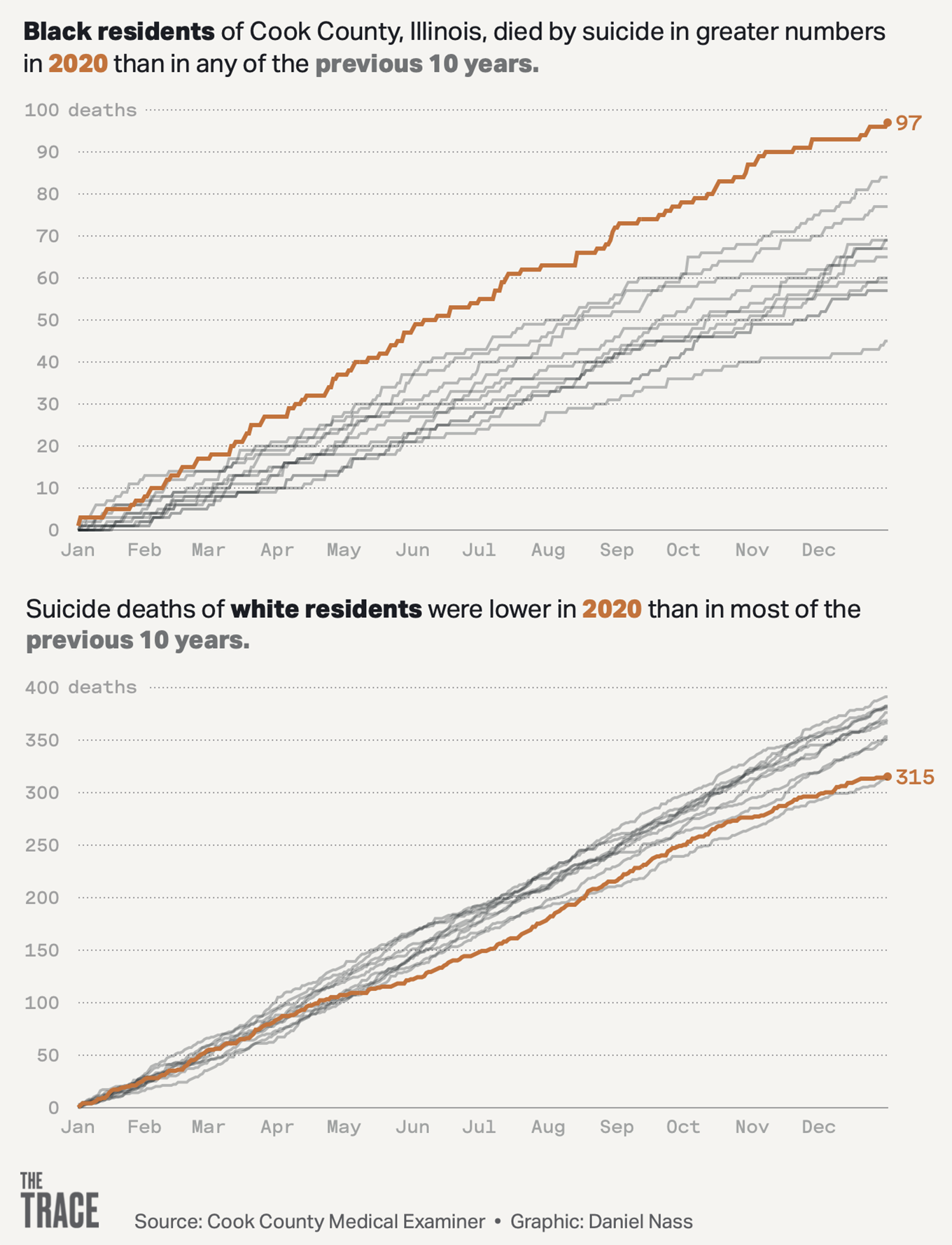

Ninety-seven Black Cook County residents died by suicide in 2020 — the highest total for a single year in more than a decade.

The alarming rise came as government officials fell short on pledges to improve suicide-prevention efforts that were made after The Trace and the Chicago Sun-Times reported last July on the rising number of deaths.

Find Support

Help is Available 24 Hours a Day

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

Free, 24/7, confidential service that provides support and connections to resources for those in distress. Call 1 (800) 273-8255 or text 1 (800) 273-8255, both toll-free.

Illinois Call4Calm

For people struggling with COVID-19-related stress who need emotional support. You can text TALK to 552020 for English or HABLAR for Spanish. This service is free and available at all times.

Illinois Warm Line

For those dealing with mental health or substance use challenges seeking support by phone. Call (866) 359-7953 toll-free to speak with professionals who have experienced mental health or substance use recovery in their own lives.

Help Someone Else

Understand warning signs.

In response, Chicago city health officials said they would seek proposals from private agencies to create and implement a suicide-prevention plan. And county officials said they were working on a similar plan and would have it by year’s end.

But neither the city nor the county came through on those promises.

The increase in the number of suicides among Black residents last year began even before the coronavirus pandemic upended people’s normal lives. An analysis of the deaths based on Cook County medical examiner’s office data shows that:

- Most of those who died by suicide were men.

- The median age was 34.

- About four in 10 of the deaths involved a gun. Less than a quarter were caused by hanging.

- And the deaths touched nearly every corner of the city and suburbs with clusters of suicides in parts of the West Side and cutting through community areas from Auburn Park to South Shore on the South Side — including areas facing high levels of violence and drug overdoses that were also disproportionately affected by the first wave of the pandemic.

- Among the deaths: A woman in her 60s in Chinatown. A 34-year-old man in Austin. And a 16-year-old boy whose death in Riverdale came just days before Christmas.

Even as the number of Black suicides rose, the number of suicides among white Cook County residents fell to a near decade low in 2020. Although there doesn’t seem to be an increase in suicides for Latinos, it’s hard to know for certain: Because of the way the medical examiner keeps records, the figures for Latinos are likely an undercount.

In July, a city official told The Trace and the Sun-Times that the city would be releasing additional funds to address mental health, including several million for the expansion of existing mental health services and $1 million for suicide prevention. The official also said the city would seek proposals for a suicide-prevention plan in late 2020 or early 2021.

In October, the city announced that more than 30 community-based mental health organizations would receive $8 million in annual grants to expand existing services. However, the grants do not fund suicide prevention specifically. Asked about the status of the city’s suicide-prevention efforts, a spokesperson with the Chicago Department of Public Health declined an interview request and said the agency was “finalizing our planning in regards to what we will be funding.”

Cook County Health did not answer detailed questions about its suicide-prevention effort. In a written statement, Dr. Diane Washington, the agency’s director of behavioral health, said the county plans to begin an online campaign focused on suicide prevention “in the coming weeks.”

“Suicide prevention and many other health disparities are still a key priority for Cook County Health,” said an agency spokesperson. “Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a key factor in shifting resources to help us fight this deadly virus and help save lives in Cook County.”

Amika Tendaji, a mental health advocate and director of Black Lives Matter Chicago, said the lack of follow-through by the city isn’t surprising.

“Chicago is known internationally for the trauma on its citizens,” she said. “We’ve got to figure out a plan and a pathway for people to heal.”

Tendaji says the pandemic has been hard on people’s mental health and that private as well as public services have been difficult to navigate.

“We have to stop discussing this as a problem of just a few people and recognize that housing insecurity, food insecurity, job insecurity — and the kind of oppression that exists in this city — is a recipe for the most marginalized to not be well in their minds or bodies,” she said.

Mental health professionals and researchers say that, although it’s impossible to tell what caused the increase in Black suicides, they suspect that the stress and isolation brought by the pandemic put people at a higher risk of depression.

Dr. Jonathan Singer, the president of the American Association of Suicidology, said prevention plans are an essential tool for governments trying to reduce the number of suicides.

“They provide a rationale and justification for local organizations to obtain funding, allocate time and resources for suicide prevention,” Singer said. “They can outline how and when data are shared, what systems are focal points for prevention activities and expectations for who in the state should be trained and involved in suicide prevention.”

Singer said it’s important to create plans with an anti-racist lens to help a range of communities, particularly because those working in the field of suicidology are predominantly white.

“We have contributed to the erasure of very real experiences in communities of color where people were dying but it wasn’t getting national press, it wasn’t getting federal funding, and it wasn’t getting its due because of the narrative that white men kill themselves — which contributes to this idea that suicide is a white people problem,” Singer said.

Jessica Newsome, director of behavioral health for Alternatives, a youth development organization that serves primarily Black and Latino families, said her organization was able to add a therapist and expand services in the Washington Park area on the South Side thanks to some additional city funding for mental health services.

But Newsome said, “It’s never enough.”

“I think CDPH is really trying and doing a really good job,” she said, but added, “The annual budget for CDPH is about $200 million, the Police Department’s is $1.6 billion.”

Newsome worries about people who, during the pandemic, are being missed by mental health providers, who aren’t getting referred for needed services and aren’t seeking help on their own.

“I think that we’re already in a situation where the young people we serve are dealing with the impact of white supremacy in their communities and community violence, and then we add in COVID,” Newsome said.

Mental health professionals in Chicago say demand for mental health services has remained steady during the pandemic. But they also say suicides are a small part of a larger mental health crisis.

“I think because these factors have been going on for so long and people have been holding on waiting for things to go back to normal — and they have not yet — we’ll continue to see symptoms present and probably get worse,” said Dr. Inger Burnett-Zeigler, a psychologist at Northwestern University who says her waitlist to accept new clients is around six months.

In November, Chicago health officials put out a public health alert on the rising number of Black suicides that noted that Black Chicagoans have the highest rates of hospitalizations for suicide attempts and face added barriers to finding affordable mental health treatment.

Newsome worries that the full extent of the problems won’t be clear until after the pandemic ends.

“That is what keeps me up at night,” she said. “I know that the wave has started. I don’t think it’s going to stop.”

Daniel Nass contributed data analysis and visuals to this story.