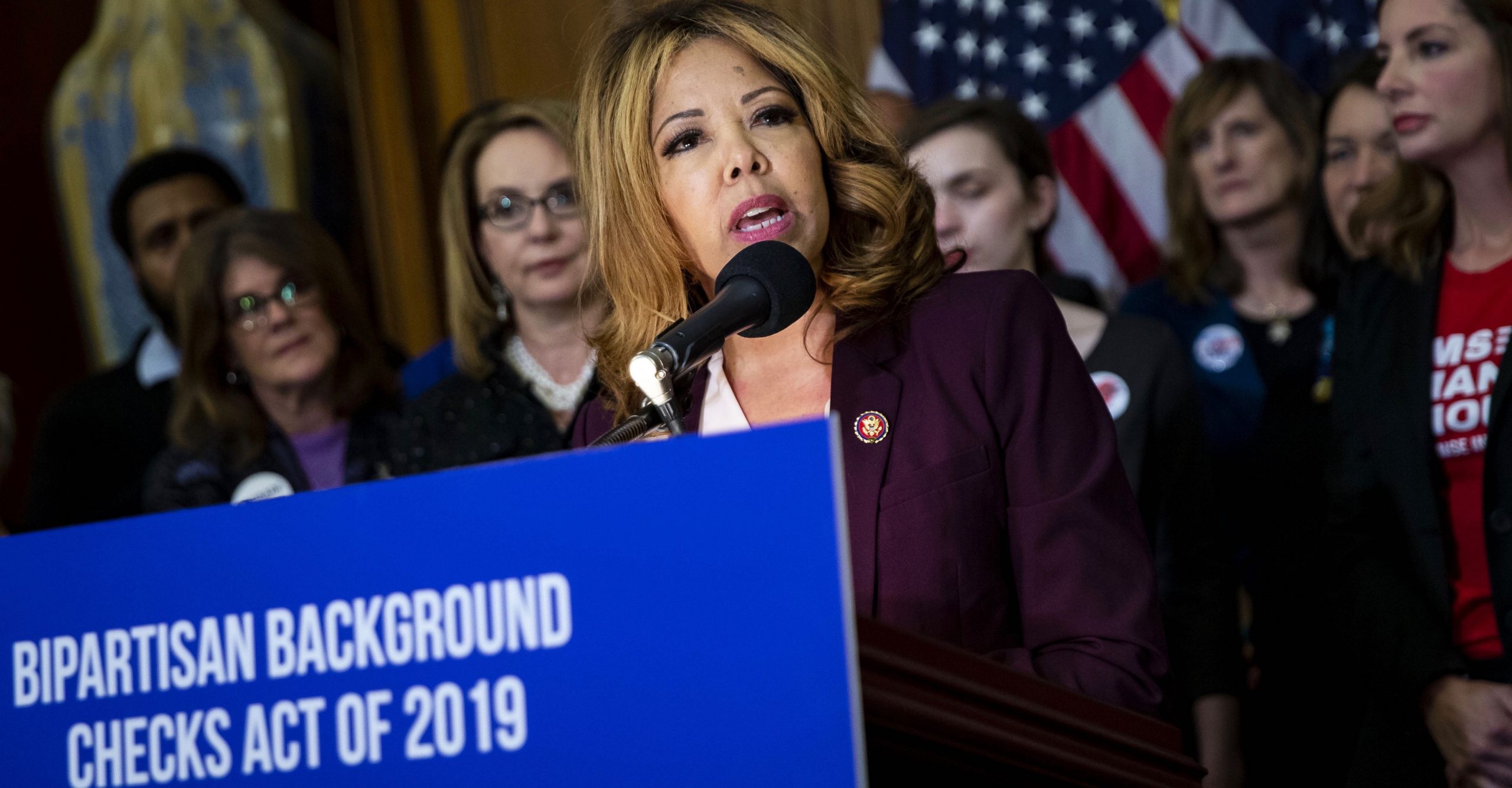

With Congress back from its August recess after a spate of mass shootings, the national spotlight has again focused on whether President Donald Trump and the GOP-led Senate will consider gun reform. Democrats have focused particular energy on expanding the federal background check system. A bill to institute universal checks passed the House in February and is currently awaiting action in the upper chamber.

Whether the Senate takes up H.R.8 remains “the number one question looming over this Capitol,” said Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer. But Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell reiterated this week that he won’t bring up any gun reform bills unless he’s sure Trump will sign them, and Senate Republicans appear to be waiting on the president’s go-ahead to act.

In light of the new momentum to bolster the background check system, here’s an updated look at our past reporting.

What Actually Happens During a Federal Gun Background Check

In the United States, anyone who wants to buy a gun from a federally licensed firearms dealer, or FFL, is subject to a background check. In 38 states, the FBI is either wholly or partially responsible for performing those screenings. Since 1998, when the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, or NICS, went online, the FBI has processed more than 320 million screenings. Given the central role that background checks play in balancing individual Americans’ gun rights and our shared public safety, we created this explainer, which covers everything from what exactly happens at the point of sale to how investigators check applicants’ backgrounds.

The 12 Reasons Why Americans Fail Federal Gun Background Checks

The overwhelming majority of background checks result in a buyer walking out of a store with a gun. Only 2 percent result in a rejection. The most common reasons for a denial include felony convictions, being a fugitive from justice, drug use, and domestic violence convictions. NICS has put a stop to more than 1.5 million attempted gun transfers by people with records falling into one of those categories. A bill currently under consideration in the House would add hate crimes convictions to that disqualifying list.

What We Know About the Effectiveness of Universal Gun Background Checks

Universal background checks are one of the most popular policy proposals to reduce gun violence. And poll after poll shows that they enjoy broad public support. Still, the record of existing universal checks is mixed. One 2012 meta analysis found little statistically significant evidence that checks reduce shootings. Two later reviews of academic literature from 2016 and 2017 strongly endorsed the policies. A landmark 2017 review of various gun policies by the RAND Corporation found only moderate evidence that checks reduce suicide and violent crime. In this piece, Alex Yablon digs into the available research.

Fewer Americans Are Acquiring Guns Without a Background Check

A national survey by public health researchers at Harvard and Northeastern universities, published in 2017, found that 22 percent of current gun owners had acquired a firearm within the previous two years without undergoing a background check. While large, that number was still a big decline from the findings of the 1994 version of the same survey, which found that 40 percent of gun sales were conducted without a background check.

Nearly Half of Americans Are Covered By Universal Gun Background Checks, but Giant Loopholes Remain.

Twenty-one states and the District of Columbia have expanded background checks to private sales, but that still leaves the majority without checks on such transfers. The background check system is also riddled with other gaps. These include cases in which sales are legally allowed to go forward if a background check hasn’t been completed by FBI examiners within three business days (known as the “Charleston loophole,” because it’s how the Charleston church gunman was able to get his weapon); and the “boyfriend loophole,” an omission whereby federal domestic violence laws prohibit gun possession for abusers who have been married to, lived with, or have a child with their victims, but not dating partners.