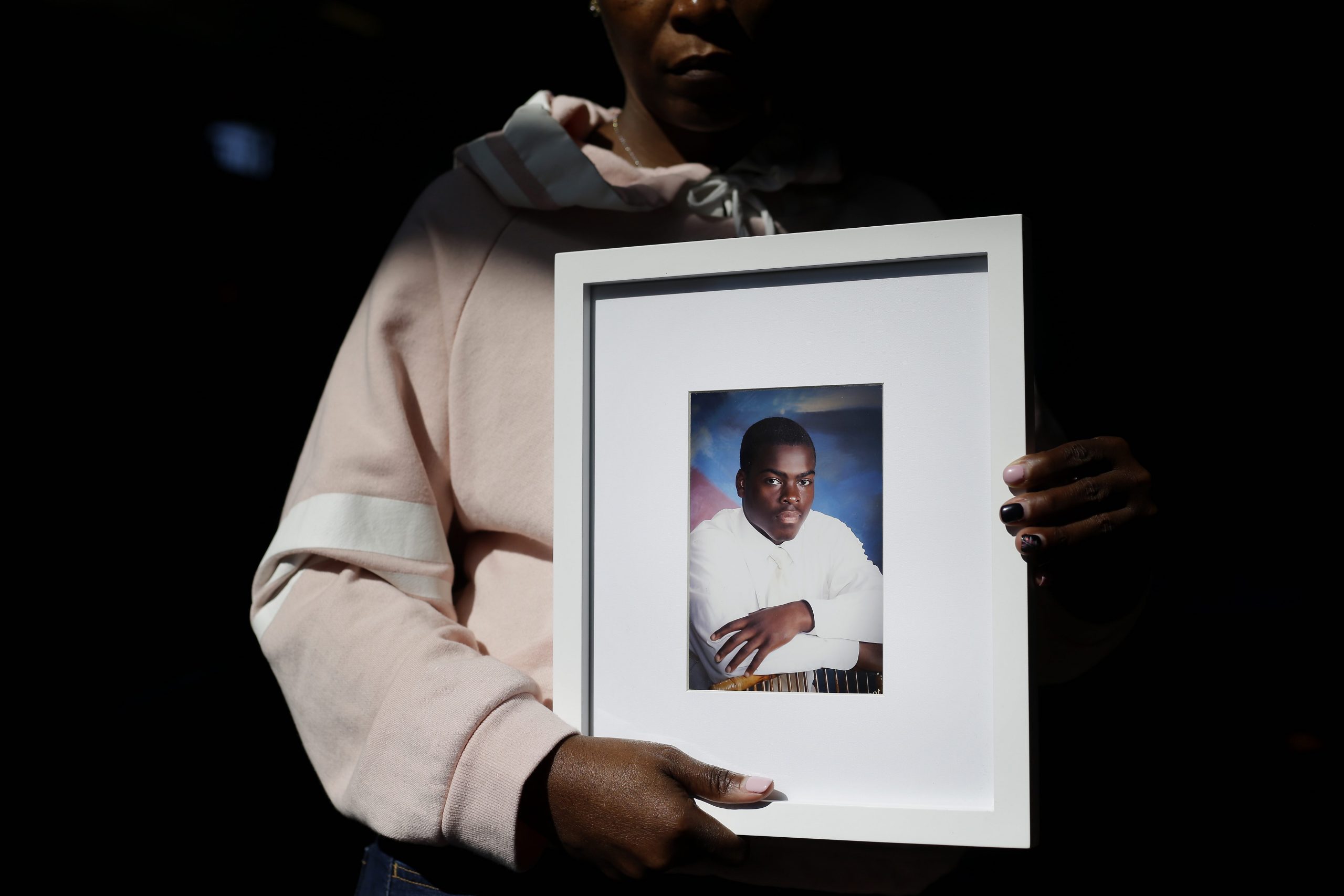

When LaVell Southern started working as a security guard in 2015, friends thought it fitting, a logical extension of his protective nature. He mentored young people through his family’s church, talked about becoming a police officer, and had been a standout defensive back on the football team at his all-boys Catholic high school in Chicago.

“One thing I loved about LaVell is he was quiet, never complained,” said Terry Beiriger, 26, one of Southern’s former high school teammates. “But I always knew he had my back.”

In the early morning hours of September 6, 2015, Southern was leaving a birthday party at the Red Kiva nightclub in the West Loop area of Chicago when a man tried to fight his friend Leonard Brinson. Police records indicate that when the man pulled out a gun, Brinson threw his hands up and tried to calm him down. Southern rushed to Brinson’s side. “There is no problem,” Southern was heard by a witness as saying. “He’s with me.”

Another assailant ran up and pistol-whipped Southern in the back of his head. After Southern stood up, he and Brinson took off running. The two gunmen opened fire. One bullet lodged in Brinson’s left arm. Another drilled into Southern’s back. He was pronounced dead at the hospital about 30 minutes later.

The two guns used in the shooting were among the more than 2,400 lost or stolen firearms seized by Chicago police between 2012 and 2016, according to an analysis by The Trace and NBC 5 Chicago. Many of those weapons were involved in the commission of other crimes, propelling a wave of violence that has roiled Chicago and garnered national headlines.

Our analysis is based on hundreds of thousands of gun theft records collected by The Trace, NBC 5 Chicago and a dozen other local NBC TV stations. The analysis also drew on more than five million lost, stolen, and recovered reports lodged with the National Crime Information Center, or NCIC, a federal database used to track missing property (a copy of which was first obtained by USA Today through a public records request). We compared those datasets with information on guns seized by the Chicago Police Department. By connecting serial numbers and other distinguishing markings, we determined that Chicago police were picking up about 480 stolen guns each year — a small but noteworthy share of the department’s annual haul of illegal firearms. Meanwhile, thousands of guns stolen in Illinois and surrounding states remain unaccounted for.

In 2016, Chicago recorded 762 homicides, the city’s deadliest year in nearly two decades. Gun thefts also surged to record levels, with 4,745 guns reported stolen in Illinois that same year, the highest number since at least 2005, when thieves swiped at least 2,770 firearms in the state, according to NCIC. In all, 41,239 guns were reported stolen in Illinois over that 12-year period. Nationally, gun theft has nearly doubled during the same period, reaching more than 238,000 stolen guns in 2016.

Strict legal restrictions on access to government data have complicated attempts to explore the role gun theft plays in Chicago’s violence. The Trace and NBC 5 Chicago’s analysis fills in some of the information gap, even though the tally of stolen guns that we relied on is almost certainly an undercount. At least some gun thefts and losses are never reported to police, and even when they are, the victims often do not know the serial numbers on their guns. Without a serial number, a stolen gun cannot be entered into NCIC, crippling efforts to link it to a crime.

“Gun theft is a huge problem in the United States, but we don’t know the entire scope of it,” said Mark Jones, a former Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives agent who is now project director with the National Law Enforcement Partnership to Prevent Gun Violence in Chicago.

While homicides in Chicago have dropped some 25 percent so far in 2018 over the same period two years ago, the flood of stolen firearms into the black market looms as a threat to the city’s progress. In a recent Urban Institute survey conducted in Chicago neighborhoods suffering from high rates of violent crime, four in five at-risk youths named gun theft as a common means through which their peers armed themselves — one far more popular than trying to acquire a firearm from a store or at gun show.

The harmful effects of stolen firearms on Chicago are manifold. A Smith & Wesson pistol yanked out of a dresser drawer fired the shot that killed a 26-year-old on the South Side in 2013. A .45-caliber Hi-Point handgun stolen off someone’s pool table was used to shoot an 18-year-old and rob another teenager in separate incidents late the following year. And a 9mm pistol snatched out of a tow truck surfaced in 2016 after gunmen stormed into a West Side cell phone store and pumped a 31-year-old full of bullets while he was standing at the counter.

Seventy-one percent — nearly 1,800 — of the stolen guns recovered in Chicago between 2012 and 2016 were pilfered outside the city limits, from as far away as North Carolina, Georgia, Texas, and Utah, The Trace and NBC 5 Chicago found. City leaders have long complained that their anti-violence work is being undermined by guns pouring across Chicago’s borders, particularly from Indiana, which is just a 30-minute drive away and has some of the most permissive gun laws in the country. In 2016, a total of 6,043 guns were reported stolen in the state, according to NCIC. That’s about 25 percent more gun thefts than were logged in Illinois during the same year, even though Illinois has nearly twice Indiana’s population.

“Guns flow in from every direction,” said Cook County Commissioner Richard Boykin, whose district includes parts of Chicago. “Many of the kids I’ve talked to, it’s easier for them to get a gun than it is to get a piece of fresh fruit.”

The Trace and NBC 5 Chicago found that most stolen guns recovered in Chicago were taken from people’s homes and cars, with thieves nabbing them out of bedrooms and glove boxes. In one case, a gun was stolen from behind the counter of a tattoo shop.

One of the guns used to kill LaVell Southern came from Arizona, where in 2011, a thief swiped a 9mm Glock out of a pickup truck parked overnight outside a community center in Phoenix. The other gun was stolen just miles from where Southern was killed, when a security guard walking home from work on Christmas Day, 2013, was robbed of his .45-caliber Sig Sauer by two assailants armed with a pistol of their own.

Hours after Southern’s killing, authorities recovered the stolen guns from the home of Andre Harris, whom witnesses fingered as the one who pulled out the gun on Southern’s friend Brinson. Harris and Deangelo Green, both 34, are facing first-degree murder charges for Southern’s death. Harris and Green had each previously been convicted of a felony, meaning neither could have passed a background check to legally purchase a gun from a store.

There is no federal requirement that gun owners lock their firearms to deter thieves. While more than a dozen states have adopted some version of a law governing the secure storage of guns, most of them only apply if the weapon could be picked up by a child. Illinois, for example, has made it illegal to leave an unlocked gun anywhere a minor younger than 14 is “likely” to gain access to it. But in wide swaths of the country, Americans are unlikely to face any legal penalties for leaving guns in places where they are easy to take, much to the frustration of Chicago officials.

“There should be some type of responsibility for gun owners to make sure their guns are safe and secure from getting stolen,” said Chicago Alderman Walter Burnett, Jr., whose district includes the area in which Southern was shot. “If people didn’t leave their guns out, maybe they wouldn’t get stolen and get out on the street.”

Also rare are laws compelling gun owners to report the loss or theft of a weapon to police. Eleven states – including Illinois – can penalize gun owners for failing to file such a report, which law enforcement officials say helps them spot trends and root out gun traffickers. But even states with reporting requirements infrequently enforce them. Authorities in Illinois, for example, made fewer than 10 arrests under the state’s reporting requirements law between 2012 and 2016.

Charges against gun owners who fail to report their stolen weapons are rarely pursued because prosecutors have to overcome the difficult task of proving that a suspect knew the gun was missing, said Katie Hill, who was then the director of policy, research and development for the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office. The penalties meted out for violations of the law are also low. The worst consequence that a first offender in Illinois could face is six months of probation and a fine of $1,000.

“The reality is that, based on the resources that we have available to us, and the way these cases come to us, pursuing them is a tool in our arsenal, but it’s not the most exigent tool in our arsenal,” Hill said.

Even though violent crime rates have plunged since the 1990s, more Americans than ever cite fear of other people as their chief reason for owning a gun. Nearly all of the stolen guns recovered in Chicago during the time period reviewed by The Trace and NBC 5 Chicago were pistols, which gun groups and manufacturers have increasingly hyped as the best tools for self-defense, leading to an explosion in their popularity.

In 2013, Jason Witham, then 25, was away with his wife on a camping trip when thieves broke into the couple’s house in Tacoma, Washington. Among the belongings the intruders took was Witham’s Smith & Wesson handgun, which he had hidden in his closet. Six months later, the gun was used to fatally shoot a 19-year-old Chicago man in what authorities described as a drug deal gone bad.

In an interview, Witham said it was “horrible” that his gun was used in a homicide but said the experience had only hardened his resolve to own firearms by underscoring the dangers he and his family faced. “I can only imagine that night, if I had been there and they had kicked in the door, if I was anti-gun, I would be dead right now,” Witham said.

Three years after his friend LaVell Southern was fatally shot, Brinson was sitting on a bench next to the field at Mt. Carmel High School, where Southern played football. “It’s right here,” Brinson said, pointing to a bulge above his left elbow where the bullet that wounded him was still lodged. The doctors told him the bullet was too close to a nerve to remove. Asked how the shooting had affected him, Brinson paused and looked down. “I just talk to myself a lot, not out loud but in my head,” he said. “I know I ain’t the same at all.”

It was a sunny Saturday in June, and Brinson and dozens of Southern’s friends had just wrapped up the inaugural LaVell Southern Flag Football Tournament, a series of games organized by Richard Russell, co-founder of the Russell & Clarke Youth Foundation and one of Southern’s former teammates. Many of Southern’s friends at the tournament remembered him as a beloved athlete who was going to college on an athletic scholarship before an injury ended his football career. The injury forced him to move back home, but he continued taking college courses and started working security and delivering groceries to save up money for his own apartment.

“Every day you think about one of your close friends being killed. It’s unreal sometimes,” said Andrew Williams, 26, who roomed with Southern in college. “I’m scared to think about it still. I don’t even like going out anymore.”

Additional reporting by Marsha McLeod.