Suburban New York City native Garrett O. Hansen had never picked up a handgun when he moved to Lexington, Kentucky, to take a job teaching photography four years ago. Settling into his new city, he soon found it was not uncommon for friends and colleagues, including those of a liberal tilt , to fire off a few rounds after work before grabbing a beer. Eventually, Hansen made his first outing to a shooting range. To his surprise, he realized he already knew more about firearms than he’d thought.

“Having never shot a handgun before, I still knew how to use it — the whole process, start to finish, ” Hansen said. “Because I’d seen it so many times in movies.”

From that personal revelation sprang Hansen’s fine-art series, HAIL. The project essentially inverts his a-ha moment on the firing line, using his lens to explore aspects of guns that go beyond the images made so familiar by the ubiquity of firearms in American entertainment.

At first, Hansen thought he would just take his camera to the range and start shooting stuff. After a few trips, the idea of focusing on what guns physically produce, and what they leave behind, stuck.

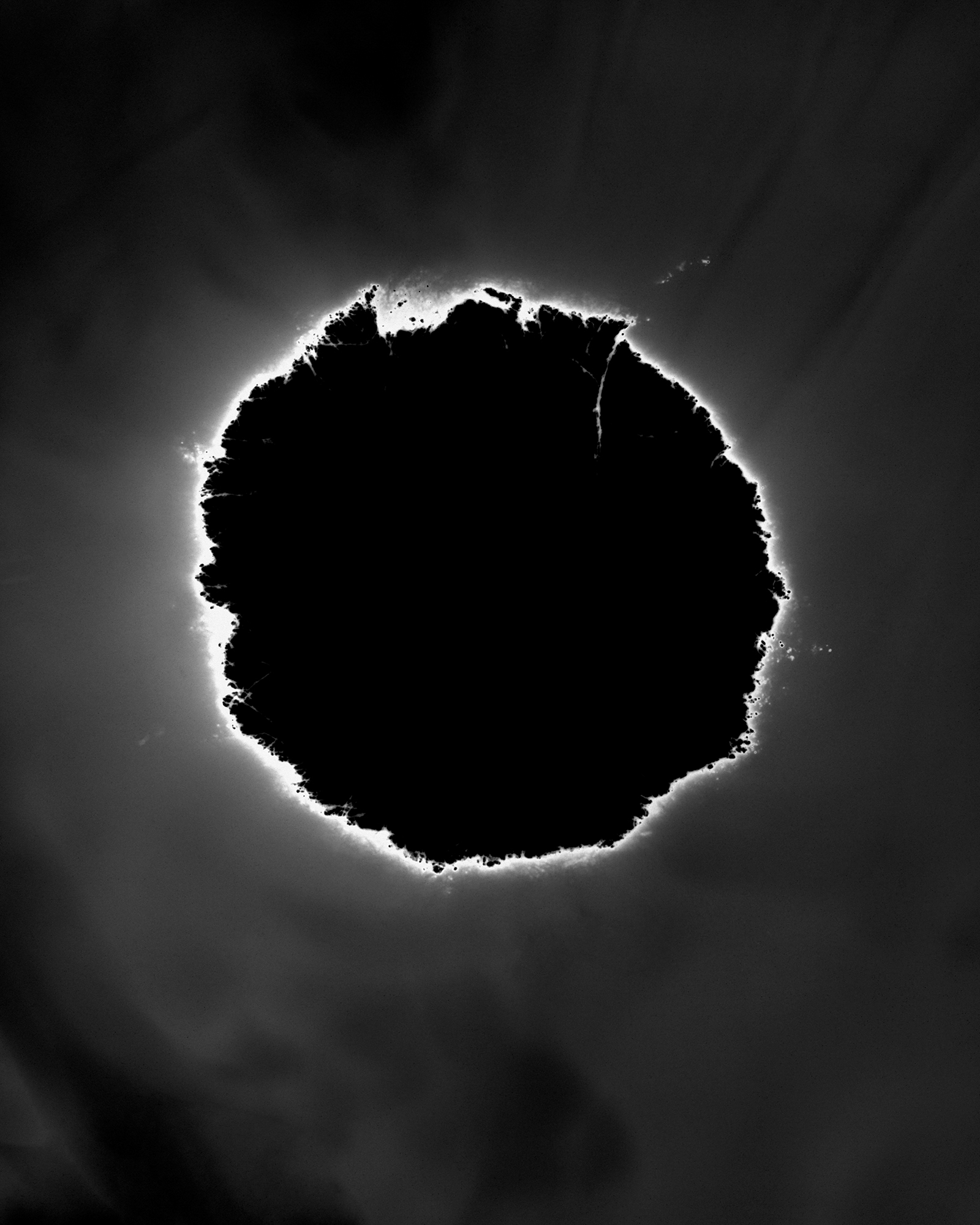

The first series in the project features images of individual bullet holes, enlarged to many multiples of their actual size. The images emanate a feeling of power and absence; to Hansen, they are also reminiscent of celestial bodies. He titled the set, “The Void.”

Hansen made the next series in the project, which he called Silhouette, by recreating cardboard backings culled from a local shooting gallery in mirrored plexiglass. The paper targets that shooters take aim at change with each patron, but the backings are reused, eroding over the course of a week. Inevitably, the parts behind the targets’ torsos and heads are most eviscerated. In a darkroom, Hansen made prints of the backings. He then used a laser cutter to create to the final pieces.

A third set, Bullets, began with Hansen and a friend going to a farm and blasting away at a ream of paper. Hanson first fired a single bullet, hoping that it would penetrate all 500 sheets, which he’d then separate out in some sort of elegant display. The projectile didn’t cooperate; it stopped a quarter of the way through the ream. His friend improvising, then unloaded on the stack of sheets.

When Hansen went to recycle the paper, he discovered his subject. To the naked eye, each of the rounds his friend had fired was identical when it left the barrel. But upon colliding with the paper, the bullets morphed into singular shapes — metal snowflakes wrought from deadly force.

“The form bullets take after coming out of the gun are fascinating,” he said. “It’s balancing destruction with creation. You have no idea what they will become on impact. They’re all unique.”

Look closely, and one of the spent projectiles looks like a human heart.

In the final series in the project, Hansen created a record of every 2016 gun homicide in the state of Kentucky and the city of Chicago. Hansen combed through news story after news story to track the deceased and learn the circumstances of their deaths — 687 of them in Chicago alone. Then he marked the deaths on twelve panels — one for each month — and assembled them side by side to create the composites that give the final set its title, Memorial.

It was wearying — but, Hansen believed, also essential — work.

“Murder statistics can become abstract,” he said. “This is a way to remember the victims. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, gun violence was massive, but then it returned to ‘normal’ levels, and it seems like we don’t think about it anymore.” With HAIL, he hopes to make the consequences of gun fire are harder to forget.

Garrett O. Hansen has pieces in Targeted, a group show at the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago, and a solo show at the Vermont Center for Photography in Brattleboro that runs through the end of July.