Late last month two immigrants from India were enjoying an after-work whiskey on the patio of a bar in Olathe, Kansas, when another patron, Adam Purinton, began shouting racial slurs, culminating with a demand that the two “get out of my country.” Purinton then opened fire.

Srinivas Kuchibhotla was killed and his friend, Alok Madasani, was wounded. Both men were legal immigrants working at Garmin, a technology company that makes GPS devices. A third man who tried to intervene was also shot and wounded.

In a heartbreaking Facebook post, Kuchibhotla’s widow said that whenever they heard of someone getting killed in the United States, she would ask her husband if they should go back to India.

“He always assured me that if we think good, be good, then good will happen to us and that we will be safe,” Sunayana Dumala wrote.

The fatal incident is being investigated as a hate crime, which the Federal Bureau of Investigation defines as “motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity.”

There is no single, reliable source for information about bias-fueled attacks in America, but there is reason to believe that they are on the rise. Police data collected by researchers at California State University, San Bernardino, shows a 21 percent increase in hate crime incidents in nine major American cities in 2016, including Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Philadelphia.

The pace appears to have picked up since the general election. Between November 8 and February 19, the New York Police Department received 143 hate crimes reports — 42 percent more than during the same time last year. The Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights organization that monitors hate groups, counted 1,372 new hate crimes in the three months following Election Day. Of these incidents, most targeted immigrants (25 percent), African-Americans (19 percent), and LGBT people (10 percent).

Authorities have struggled to respond. Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat from Connecticut, has proposed a bill calling for tougher federal laws. The legislation would offer incentives and resources for law enforcement to submit reports on hate crimes.

Hate crime data collected through victim surveys and law enforcement agencies indicate that most incidents don’t involve a gun. Those that do, however, tend to draw the most media attention because they often have the most frightening implications.

In 2012, a federal raid averted an attack in Bowling Green, Ohio, by a white supremacist who planned to target African-Americans and Jews. In 2015, nine black worshipers were gunned down in a Charleston, South Carolina, church by a white supremacist. Last month, another South Carolina man was arrested by the FBI after buying a handgun from an undercover agent, saying he wanted to commit a white supremacist attack “in the spirit of Dylann Roof,” the Charleston killer.

Here’s what we know — and don’t — about the prevalence of hate attacks, and what happens when firearms are involved.

How many hate crimes happen every year in America? It depends on what source you consult.

A dearth of information about hate crimes in America has inspired a reporting project: the ProPublica-led “Documenting Hate.” The chart above makes an awfully convincing case for why such an initiative is needed. The two most commonly cited sources for bias attacks, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report and the National Crime Victimization Survey, conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), come to vastly different conclusions about the prevalence of such attacks. Neither source provides much granular detail about the nature of the threat.

The FBI’s statistics are based on reports collected from 15,000 law enforcement agencies — about 80 percent of the total. Reporting is voluntary and many state, city and local police agencies fail to report the data or simply don’t collect it. In addition, more than half of hate incidents are not reported to the authorities in the first place.

The crime victim survey suggests the true number is far higher: it estimates 1.4 million hate crimes between 2010 and 2015. An estimated 46,500 of these hate crimes — 3 percent — were committed with a firearm, according to an analysis of BJS data by the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning public policy group. That works out to about 20 a day. Even if that is a small fraction of the total, that seems a startlingly high number of incidents.

A June 2017 BJS analysis of crime victim survey data suggests that the problem is even more dire: Of the 2,301,310 violent hate crimes committed between 2006 and 2015, 4.5 percent were perpetrated with a gun, which works out to 28 a day.

A common criticism of self-reported surveys is that the individual incidents are not verified, and they can over represent the nature of a problem.

The FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting program does not give a breakdown of how many hate crimes involved a firearm. But another, smaller database used by the FBI, the National Incident-Based Reporting System, does describe the type of weapons used in bias attacks. While the NIBRS is generally considered the most detailed source of hate crime data, it only includes records from 6,500 of the nation’s police departments. The result is an even smaller sample of incidents.

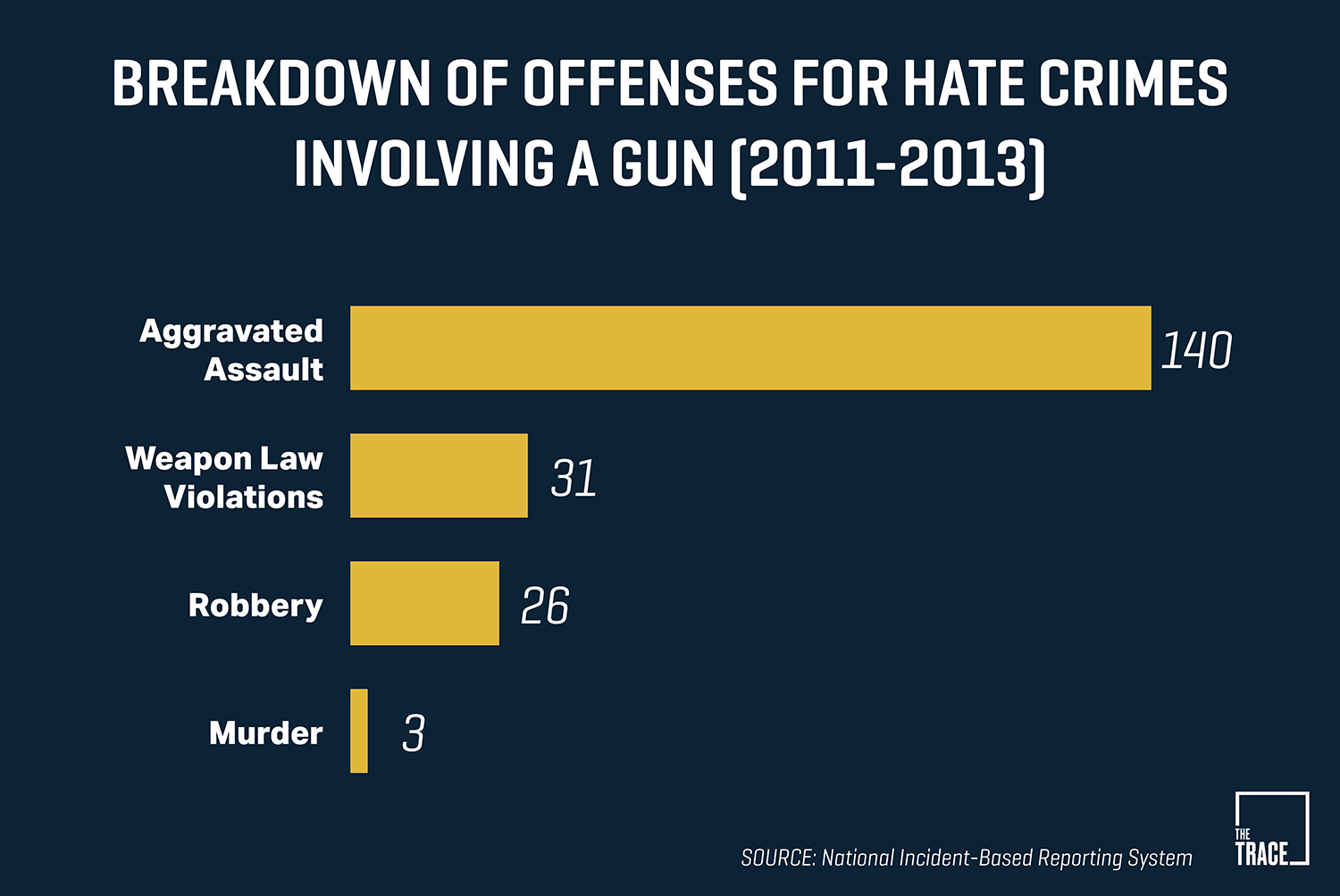

In 2015, The Trace and researchers at John Jay College of Criminal Justice analyzed hate crime data collected by NIBRS. The analysis looked at incidents between 2011 and 2013. Of the 8,132 hate crimes logged, 207 were committed with a gun. Black victims were targeted with firearms by white offenders 20 times more often than any other racial group.

In one sample of incidents in which a gun was involved, the weapon wasn’t fired most of the time

The Trace’s analysis of the FBI’s incident-based reporting data found that in most cases the attack didn’t result in any injury. Of 207 hate crimes committed with a gun in a three-year span, 107 left victims physically unharmed and 25 caused minor injuries. That doesn’t mean there wasn’t any harm done: the psychological damage resulting from being threatened with a gun can be devastating.

When a gun is pulled during a hate crime, the offender is often “trying to get the victim to do something — move out of a neighborhood or leave a workplace or school,” said Jack McDevitt, director of the Institute of Race and Justice at Northeastern University. The firearm is used “to make the threat more credible.”

Attacks on one of the most vulnerable populations in America are on the rise

According to the Gay and Lesbian Alliance against Defamation, GLAAD, 27 transgender people were victims of homicide in 2016 — the deadliest year on record. More than half of the killings were carried out with a gun.

Already in 2017, seven transgender people have been killed. Five died of gunshot wounds. The majority of victims are transgender women of color — like Chyna Gibson, who was shot and killed in February at a Mardi Gras celebration in New Orleans, a week after her gender-reassignment surgery.

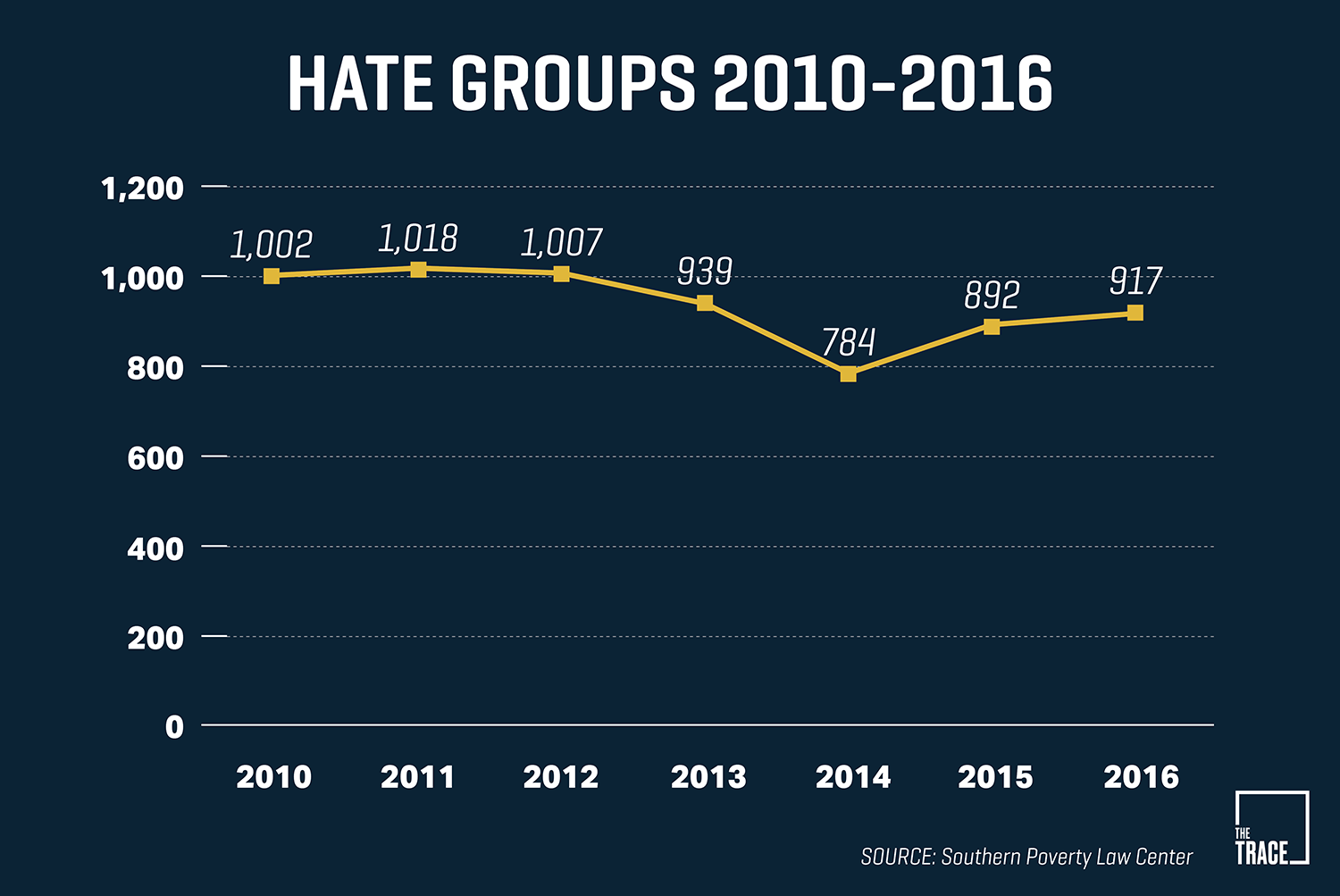

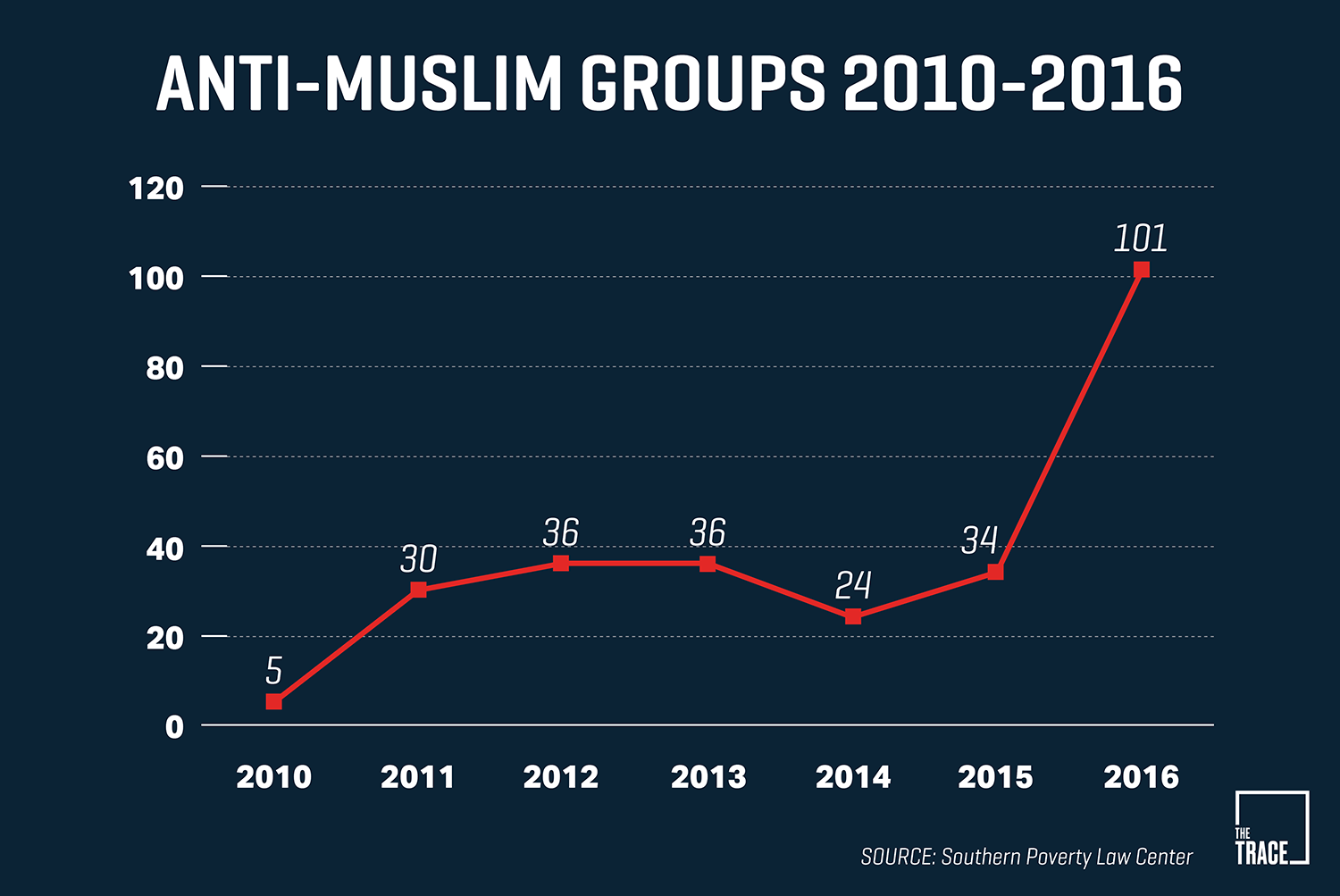

While hate groups in general are on the rise, anti-Muslim groups have seen an exceptional increase.

The number of hate groups active in the United States ticked up to 917 in 2016 from 892 in 2015. The Southern Poverty Law Center says that figure may under represent the total number of hate groups operating in the country. The organization warns of a “growing numbers of right-wing extremists [who] operate mainly in cyberspace until, in some cases, they take action in the real world.”

The number of groups targeting Muslims has significantly increased. In 2015, there were 34 anti-muslim groups. Last year, that number grew to 101.

The growth of anti-Muslim groups coincided with a surge in crime against Muslims. Bias incidents targeting Muslims increased by 67 percent, from 154 incidents in 2014 to 257 in 2015, according to the most recent FBI statistics. It’s the highest number since 2001, when the FBI recorded 481 hate crimes involving Muslim victims in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks.