On December 13, Sade Dixon’s ex-boyfriend banged on the door of the Orange County, Florida, home she shared with her family. When Dixon answered, he shot and killed her. Then he shot Dixon’s brother, who had rushed to her aid. Dixon left behind two children, ages five and seven. She was three months pregnant.

A few weeks earlier, Kortni Thornton’s estranged husband shot her 18 times at her grandmother’s Milwaukee apartment. She was pronounced dead at the scene.

And two months before that, in a neighborhood not far from the scene of Thornton’s murder, Nya Hammond, a teenager, was gunned down by the father of her 3-year-old child on the way to work. Hammond had showed her mother pictures of bruises Pierre Gardner had left on her body after he beat her with an extension cord two weeks before the shooting.

When a woman is murdered in the United States, an intimate partner — a former or current dating partner or spouse — is often to blame. Black women like Dixon, Thornton, and Hammond are especially vulnerable. One government report found that African-American women were four times more likely than white women to be murdered by a boyfriend or girlfriend. Researchers say the phenomenon can be largely explained by the position black women occupy on the socioeconomic scale.

Intimate partner homicides of both whites and blacks of either sex declined from 1976 to 2005, but black women are still dying at a disproportionate rate.

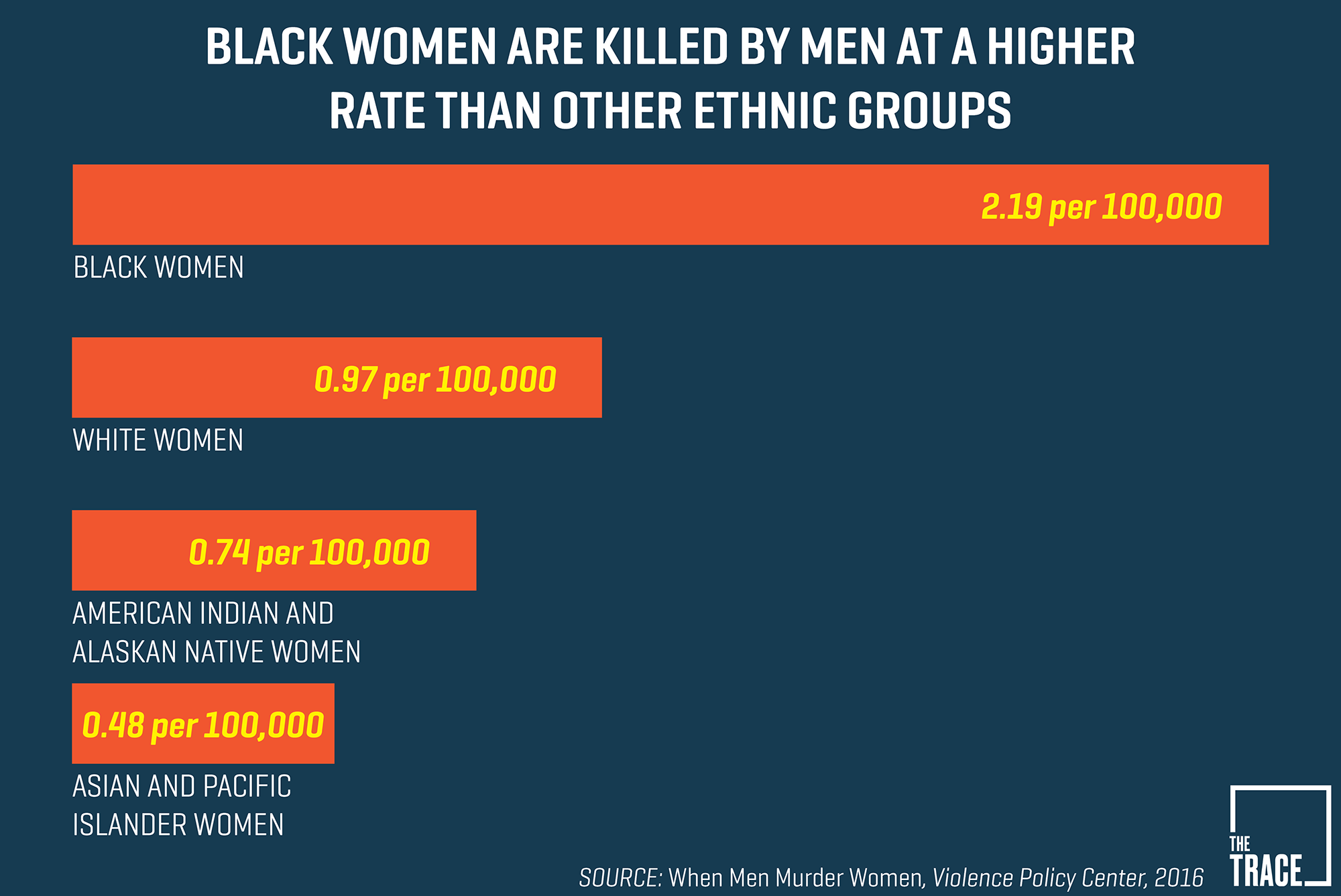

Using data provided by the FBI, a report by the Violence Policy Center, an organization that conducts research on American violence, analyzed every instance in which a lone man killed a woman in 2014. During that year, black women were murdered at more than twice the rate of white women. Of black victims who knew their killers, 57 percent were killed by an intimate partner.

In more than half of cases where the weapon could be identified, black women were killed with a firearm, according to the report.

Oliver Williams, a professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Minnesota and co-director of the Institute on Domestic Violence in the African American Community, has been studying domestic violence in the black community since the 1980s.

“African Americans are disproportionately low income, and statistically, folks who live in low-income environments show higher rates for domestic violence,” Williams told The Trace.

Research from the National Institute of Justice shows that domestic violence is more prevalent and severe in disadvantaged communities and occurs more in households facing economic distress. The unemployment rate for African Americans is nearly twice the national average. Black men are unemployed at a rate more than twice as high as the rate for white men, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 92 percent of incidents where a black woman was killed in a domestic violence situation, her intimate partner was also black.

Distrust of law enforcement could be another contributing factor to the disproportionate rate of domestic violence homicides among black women, according to Carolyn West, an associate professor at the University of Washington and editor of Violence in the Lives of Black Women: Battered, Black, and Blue. Tensions between African Americans and law enforcement, she noted, can keep black women from reaching out to police and the legal system for help.

“The only source of help [in domestic violence situations] seems to be the legal system, which has never been friendly to African Americans regardless of abuse status,” West said. “Not to say that there aren’t some police officers who are helpful, and want to be helpful, but I think when there’s that tension there, [black women] certainly may not see the police as a source of help. Then the violence just escalates.”

[Photo: GoFundMe]