MILWAUKEE — Kemmick Holmes doesn’t like to leave the house. The 40-year-old former felon says he has been robbed at gunpoint five different times in his city, and that he gets anxious every time he walks out his front door. But on Election Day, he forced himself to walk to his polling site, a police academy down the road, on Milwaukee’s north side. Once inside, an elderly lady showed him what to do. Holmes filled in the bubble beside Hillary Clinton’s name, slid the ballot into the machine, walked back to his apartment, and called his mom. He was elated. He told her he had just cast his first-ever vote.

“I felt like I was going to make a difference,” he recalls. “I even put the little sticker on my hat.”

Many Milwaukeeans did not share the optimism that carried Holmes to the polls. During the primaries in March, Hillary Clinton held a forum at Tabernacle Community Baptist Church in the heart of the north side. She described how she would tackle the “epidemic” of gun violence concentrated in pockets of American cities like Holmes’ side of town, where people are “short on hope.”

The discussion was meant to shore up her support among African Americans — and hopefully provide a jolt of that hope — but Clinton didn’t come back. While she won 77 percent of the vote in Milwaukee, 41,000 fewer registered voters turned out than in 2012. Clinton appears to have lost the state by about 22,000 votes. It was the first defeat for a Democratic presidential nominee in Wisconsin since 1984.

The head of the city’s election commission says new voter ID requirements may have deterred thousands from casting ballots. But many locals, interviewed over a long weekend after the election, say they noticed a sharp drop in energy from the previous two election cycles, when Barack Obama was on the ballot. Some had hoped the election of the nation’s first black president would rejuvenate their community, but instead things seem to have stayed the same — or gotten worse. Homicides went up and trust in institutions fell. There aren’t enough jobs, and the industries that once sustained the city don’t seem likely to come back. Residents say they struggle to see a future for themselves. They don’t much believe that a president can restore what they have lost.

“Voting is all about voice, having a say,” says Muhibb Dyer, a poet and activist who leads anti-violence workshops for young people across the city. “To become politically active and politically conscious, you have to know that you count, and that you matter. And if everything in society tell you that you don’t matter, sometimes you give up.”

Once a major manufacturing hub, Milwaukee struggles with high rates of poverty, unemployment, and violence. It is one of the most segregated cities in the U.S., and has been deemed the second-worst city for black Americans, according to the financial news site 24/7 Wall St. Last year, there were more murders per capita than in Chicago — 84 percent of the victims were black. A fatal police shooting over the summer deepened resentment between law enforcement and residents.

Amid their daily concerns, like violence and money troubles, some residents said voting just didn’t seem that relevant.

“I heard a guy say, ‘I voted before and the price of Ramen noodles hasn’t changed,’” says Simon Warren, a political and community organizer whose 21-year-old son was fatally shot last year. “In other words, ‘My condition hasn’t changed.’”

On a Thursday evening, a week before Thanksgiving, Debra Jenkins maneuvers her old Buick around downtown, past City Hall, where police officers direct pedestrians to the annual Christmas tree lighting. Strings of lights twinkle in trees. A youth choir prepares to sing carols.

Then she heads north, up Martin Luther King Drive. A few minutes later, the festive lights have disappeared. Main thoroughfares are lined with closed-down businesses. On the residential blocks, homes are boarded up. Some have been converted into corner taverns, whose windows cast yellow light into otherwise dark streets.

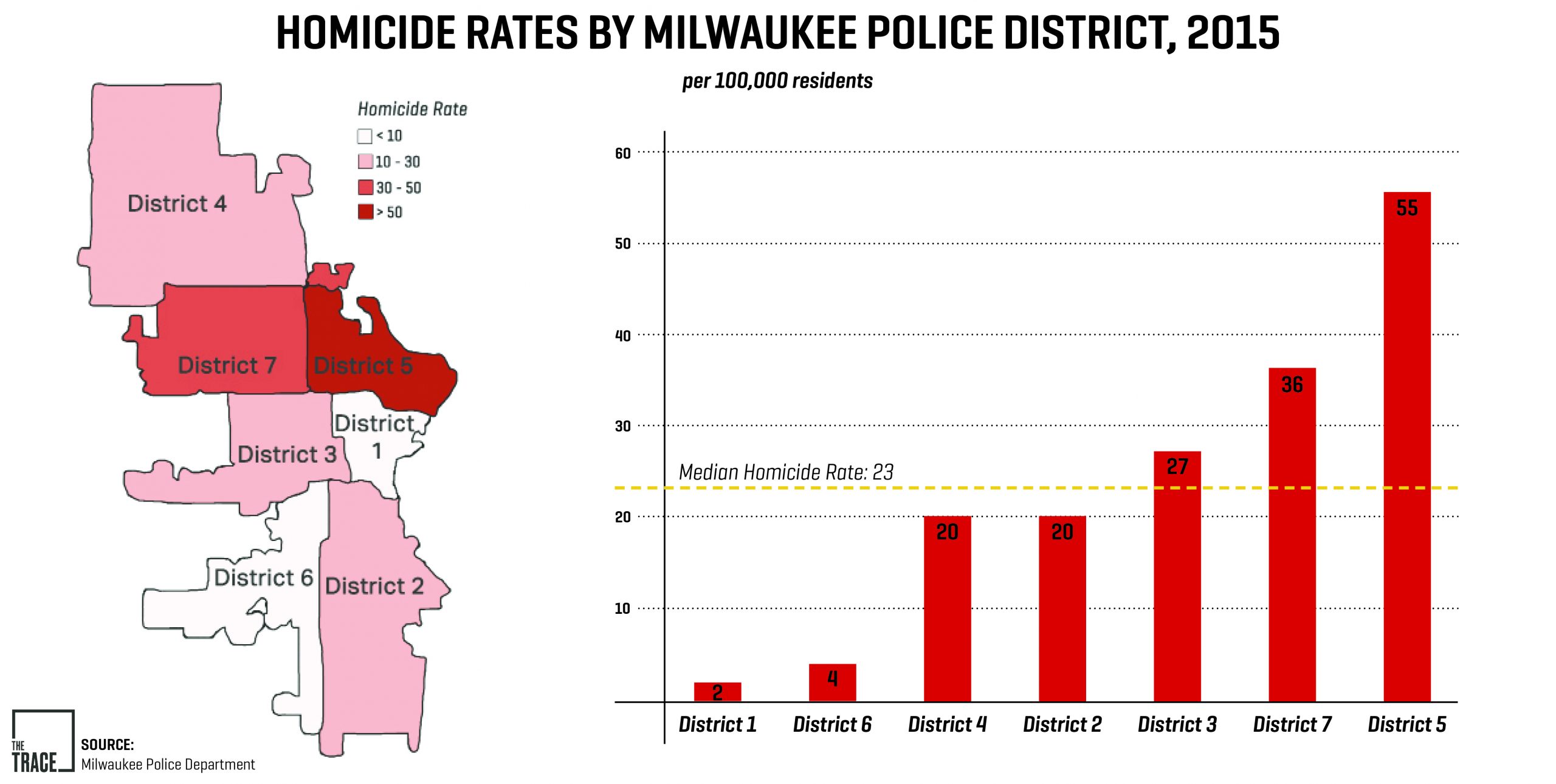

“Five-three-two-oh-six,” Jenkins says, announcing the zip code. It is, statistically, one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the country. The zip code falls in the 5th Police District, where the homicide rate is more than 20 times that of the city’s safest district. A recent documentary explored the zip code’s legacy of having among the highest per capita incarceration rates in the country. Nearly two out of three adult men have spent time in prison.

“Lot of shootings, lot of people getting killed in this little area,” Jenkins says.

She continues her tour, passing an elementary school where an 8-year-old boy brought an unloaded gun earlier that week. Across the street, tea lights are arranged around a tree in remembrance of one of the city’s recent shooting victims.

Jenkins loves her city. She grew up on the west and north sides, and worked for three decades in a factory that made gasoline engines. But in 2002, her son Larry was fatally shot by a police officer. Since then, she’s become consumed by her son’s case, filling dozens of binders with articles and court documents. She sometimes feels angry that while some police shootings draw national attention, many more haven’t. “I’ve been fighting for 14 years … Larry’s name don’t mean nothing.”

She and other mothers play self-appointed watchdogs of Milwaukee’s murders, maintaining a running tally of killings that they update monthly. According to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, more than 130 people have been murdered in the city so far this year. Most were shot.

At times, Jenkins talks about her hometown as if it’s a fruit left to rot. “The city of Milwaukee is almost in a decayed mode,” she says. “We have lost just about everything. We don’t have any confidence in our police department. The mayor hasn’t showed much. So we were looking for that great white hope in Hillary.”

Vaun Mayes-Bey is a 29-year-old community activist and founder of We All We Got, a local movement to empower black Milwaukeeans and ease tensions with police. Dynamic and resourceful, he is the kind of person a campaign might recruit to mobilize get-out-the-vote efforts. But Mayes-Bey says he didn’t even cast his own ballot. He says he doesn’t believe his vote would have mattered. He hopes the election results get people “to stop relying on the elected officials that fail them so much and start relying on themselves.”

For the past five months, Mayes-Bey has been busy keeping the peace around Sherman Park. Over the summer, the park was the epicenter of unrest, partly provoked by the killing of Sylville Smith, 23, by a police officer. Dozens of young people rioted, looting and setting fire to businesses. All that remains of the BP gas station across the road is a charred frame.

The Journal Sentinel reported in August that “concentrated poverty, high unemployment, pessimism about the future, hollow promises from politicians, [and] a sense of relentless oppression” contributed to the turmoil. Mayes-Bey says there was yet another ingredient: boredom. “There is nothing in our city for our youth to do,” he says. He started organizing activities in the park — meals, movie nights, mentoring — to keep young people occupied.

On a recent afternoon, he and other community organizers are at the park offering free food to the hungry. A blur of red streaks over from a nearby road. It’s Junior Harris, a 16-year-old wearing a Wisconsin Badgers sweatshirt. Still out of breath, Harris describes how moments earlier, he’d been riding a city bus with some friends when a white man told them they were being too loud. “He got to talking stuff, ‘You’re some niggers, you idiots, you’re not intelligent,’” says Harris. “When he said it again, that’s when it triggered me and I got mad, and I guess I got to fighting.” He says he threw some punches before jumping off the bus.

Two Sundays after the election, a cold front has moved through Milwaukee. At All Peoples Church, two miles from where Clinton spoke about gun violence, congregants arrive to find the boiler has broken, leaving the main sanctuary frigid. They gather in the basement to sing and worship bundled in their coats and gloves.

Leading the service is Reverend Steve Jerbi, who says his congregation is black, white, and Latino — an intentional antidote to the city’s legacy of segregation. (Jerbi discussed how regularly bloodshed touches his community in a recent episode of Precious Lives, a 100-part radio series about gun violence in the city).

Sitting in the back row is Xavier Thomas, the youth director at All Peoples. Thomas, 29, says he wasn’t moved by either presidential candidate. He had a hard time imagining how they would rebalance the sorts of inequities affecting the young people he works with: incarceration, missing fathers, hunger. “There’s many times I’d like to take one of the kids and just have him come with me for a week or something,” he says.

By the end of the service, Thomas’s phone is dead. “You have no idea how nervous I am to turn it back on,” he says. He can’t decide which is more anxiety-provoking: missing a phone call bearing bad news, or picking it up. One night this past summer, one of the young people he works with had called to say his father had been killed. Thomas says he worked so many funerals over the summer, “it became the routine.”

He says he recently came to a sobering realization. His job, which was supposed to be about inspiring young people, is really about consoling them. He feels like he is fumbling his way along.

“I should be focusing on uplifting them and helping them become the best them they can be, helping them become that next engineer, that next social worker, that next preacher,” he says. “Instead I’m talking to them about how they’re scared to leave their house, and trying to help them get over their fears of living here.”

He says he would benefit from a class on how to guide kids through their grieving. He says if that powerful emotion is not properly channeled, it feeds into an unstoppable cycle. “Without grieving, you turn that into anger, and the anger turns into retaliation, and retaliation turns into another family’s loss.”

Later that Sunday, Kemmick Holmes, the first-time voter, takes a Xanax and walks to the McDonald’s near to his house. In his younger years, he says he was a constant fixture on the streets. Now he hates being in public.

Originally from Mississippi, Holmes says he moved to Milwaukee in 1994 to be closer to his father. But once his dad passed away a few years ago, the anxiety and panic attacks set in. “I have no one I trust in Milwaukee,” he says.

Sitting on the corner edge of a booth, Holmes finishes his cheeseburger and takes a sip of an icy orange drink.

Before the election, he’d had high hopes for Clinton. “I voted for her ‘cause she was more experienced with things around the White House … For people like me, she probably would have come up with a way for us to get good medical insurance. She was gonna help with minimum wage. She said she was going to make tougher gun control.”

Donald Trump, he says, “is just a hustler.”

He predicts in light of Trump’s win, racially driven incidents will continue across the country. But he’s more worried about what might await him outside, right now. When he’s out and about, he knows better than to take his eyes off the streets and glance down at his phone. Do that, it’s over. Holmes makes a clicking sound, and raises two fingers to his neck in the shape of a gun.

[All photos by Pat Robinson for The Trace]