An American woman is shot and killed by her partner every 16 hours. But guns don’t just kill women; they’re also often used to scare and control them. A new study from University of Pennsylvania, reported in the Trace yesterday, estimates that 4.5 million women have been bullied or coerced with a firearm by an intimate partner.

Leslie Morgan Steiner is one of those women. Here (with her ex-husband’s name and other identifying details changed) she writes about what it’s like to live with the knowledge that a violent partner has a collection of guns at the ready.

Conor first attacked me five days before our wedding. In the little ranch house we’d bought to start married life together, he choked me and banged my head against a wall. His fingers left ten red-brown bruises on my neck. They faded just in time for me to put on my mother’s wedding dress and marry him, despite what he’d done.

I’d met Conor the year I turned 22. Back then, I had never seen or touched a gun. I’d just graduated from college and was a writer and editor at Seventeen magazine. Conor was a Wall Street trader. We met on the New York City subway, and after a whirlwind courtship, I agreed to marry him and leave my job and the city I loved to start a new life with him in a small town in New England.

After that first assault, I assumed he’d never hurt me again, because I knew that he loved me. I also knew Conor’s secret: that he’d been repeatedly abused by his stepfather as a child. But I didn’t know anything about the longterm impact of childhood trauma, or how difficult it would be for him to keep his abusive past out of our marriage.

A week after he strangled me, on our honeymoon, he punched me in the face. As we drove home from the beach cottage where we’d spent our first days together as a married couple, he threw a cold Big Mac at me in a fit of rage.

The first time Conor came home with a gun, we’d been married for three months. Gun ownership was widespread and legal in the rural state where we lived. Conor’s new company had an employee gun range, the way other corporations had gyms or daycare centers. I froze the first time I saw Conor’s gun, which looked like a matte black children’s water pistol, sitting on our dining room table next to a bowl of apples. It turned out to be something called a Glock.

Conor smiled when he saw my surprise.

“We need to stay safe, babe,” he explained. “You have no idea how violent people can be. You grew up so sheltered. I want you to be able to protect yourself when I’m not here.”

Living with loaded guns, especially in a small town with almost no crime, in a household where the guns were not for hunting or recreation, baffled and frightened me. It undermined my sense of safety in my own home.

The manipulative tactic of “gaslighting” always comes this way — disguised as love and concern, it’s really an attempt to deny someone’s perceptions. That Glock was not there to keep me safe, though it did make Conor feel strong in ways he’d never felt as a child. As a young boy, his mother had stood by helplessly as his stepfather broke Conor’s arm, his ribs, his collarbone. His stepfather also beat his mother in front of Conor. What I couldn’t see as his wife was that Conor’s power came at my expense. If he kept me insecure and afraid, I couldn’t leave him, couldn’t abandon him the way his mother had.

For that, the Glock soon wasn’t enough. A few months later, Conor came home with a Colt .45. Next was a Smith & Wesson .38 snub-nosed pistol. He put the .38 in his pants pocket, the Glock in our car’s glove compartment, and the Colt .45 under the pillow of our bed. He kept them loaded with hollow point bullets. A cold shiver ran through me when Conor explained that this type of ammunition “worked best” because it exploded upon impact with human flesh.

Conor insisted I clean his guns and join the National Rifle Association; on weekends, he pressured me to accompany him to the gun range. Conor acted as if he were teaching me a shared hobby, like fly fishing. To me, having guns in my house, my car, and my life was like drinking poison in our tap water every day. I couldn’t see, or measure, the danger. But bit by bit, living with Conor’s guns destroyed the trust I had in the man I loved. And in myself.

I know now that abuse victims face a 500 percent greater risk of death if they live in a home with firearms. I know now that between 2001 and 2012, more American women were shot to death by a current or former boyfriend or husband than the total number of American troops killed in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars combined. I know now that the most dangerous time in an abuse victim’s life is after she leaves her abuser, because the majority of homicides occur after the relationship has ended. And that usually, the murder weapon is a firearm.

I didn’t know any of that then.

I didn’t see myself as a battered wife. I was a strong, smart, independent woman in love with a deeply troubled man. I told myself he needed these guns to feel safe, after all he’d suffered as an abused child. I thought I was the only person on earth who could help him stare down his childhood demons. I thought I could take it.

I was misinformed about this, too.

Once or twice a week, when Conor got angry — because I forgot to buy milk at the store or overcooked pasta, because I had talked on the phone with a male friend from college or my voice reminded him of his mother — the fights often ended with Conor pressing one of his loaded guns, usually the larger Glock or Colt .45, against my temple.

I don’t remember feeling afraid he’d pull the trigger. I don’t remember feeling anything. The next morning, looking in the bathroom mirror at the circular bruise the gun barrel had left on my face, it seemed impossible that my own husband had used a loaded pistol to mark me like that. That’s the most insidious part of abuse. Even with the obvious danger of guns, the violence escalates so gradually, you don’t realize how crazy your life has become. Conor never had to pull the trigger; the numbness that came over me from living under the incessant threat of violence was incapacitating on its own.

When I finally left Conor, five years after I first met him, one of the first things I did was to put his three guns in a cardboard box and walk the box to the police station a few blocks from the home we’d shared. Months later, as a term of our divorce settlement, Conor’s lawyer stipulated that I had to give the guns back. I refused. Conor got them anyway.

In the years since, Conor remarried, had a child, and started a company. I moved as far away as I could, setting up an unlisted phone number and a P.O. box for my mail. Eventually I remarried and had children, and wrote a book about loving, and leaving, an abusive man.

It’s been over 20 years since I’ve seen or heard from Conor. But if I saw him again, my body would shake involuntarily. I believe I will always be afraid of him. I fear for the other women in his life, too.

When I think of Conor today, I have to wonder, and worry: Where are those guns now?

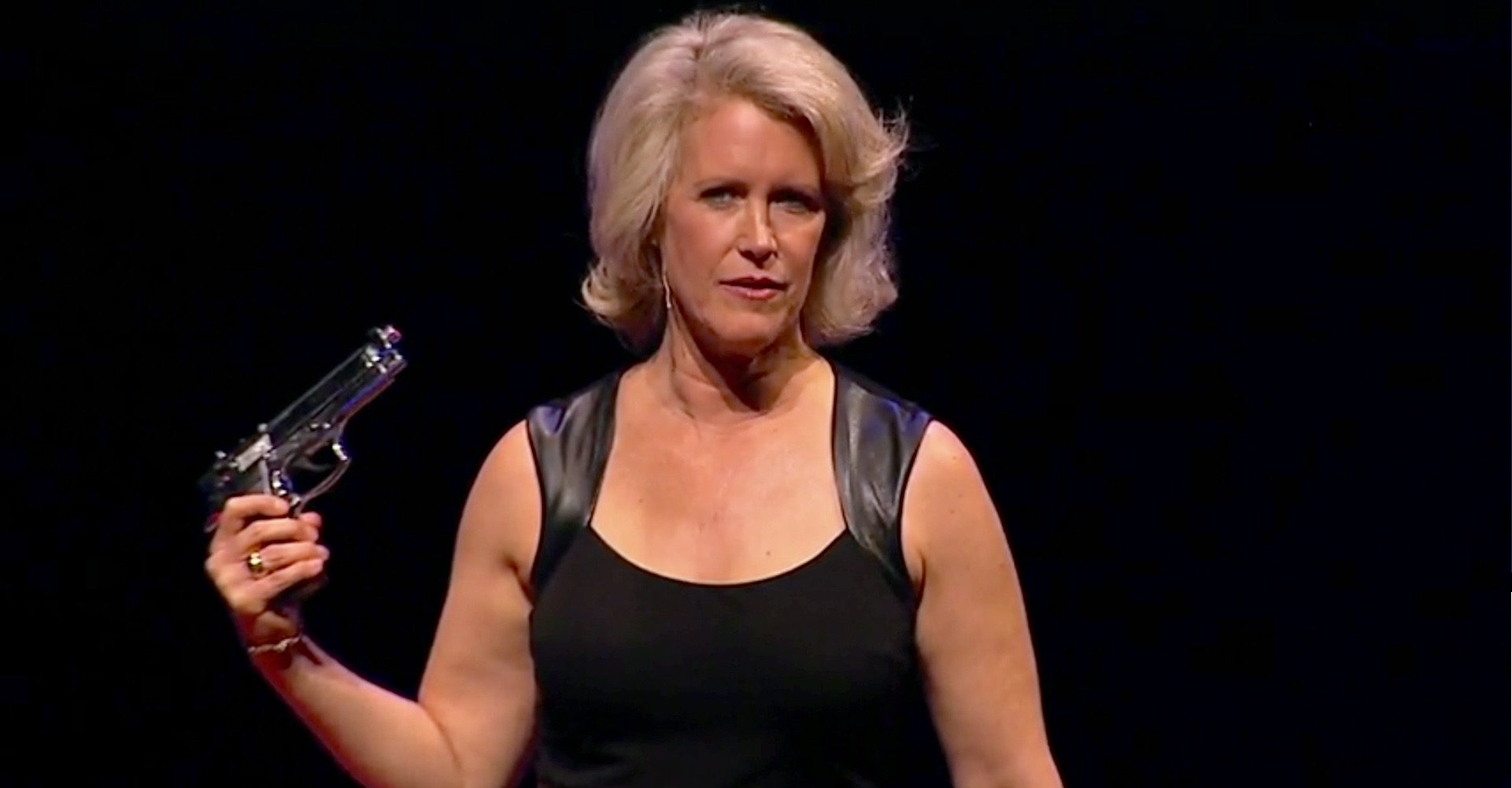

Leslie Morgan Steiner is the author of Crazy Love, a New York Times bestselling memoir of domestic violence. Her TEDTalk about why victims stay has been viewed by over three million people. She lives in Washington, D.C.

[Photo: Ted.com]