The federal government is trying, once again, to give a boost to smart gun technology. In late April, the Obama administration launched a pilot program that seeks to enlist police departments in testing weapons equipped with technology that prevents firing by anyone but authorized users.

The promise of smart guns is their safety features: the weapons are useless if stolen, and cannot be fired by a curious child or an assailant who wrests it from a gun owner’s grip. If cops embrace smart guns, the thinking goes, so may civilian gun buyers, many of whom now view the prospect of firearms outfitted with computer technology with deep suspicion. The plan is premised on untested assumptions, including that the technology is ready for mass deployment, that police officers will agree to carry the weapons while on duty, and that wary consumers will agree to pay extra for guns some fear will behave like a balky smartphone when they need them most — while repelling an attacker.

There are, however, several lower-tech ways to make guns safer, methods that have been available for decades. These options do not go so far as to render a firearm inoperable if it falls into the wrong hands, but they have proven effective at helping prevent accidental discharges, which claimed 586 lives in 2014, the most recent year for which Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data is available.

Though the safety features listed below are well known, they have not been universally adopted by gun makers. That’s because no federal agency oversees how firearms are designed or built, even though federal safety regulations are standard for other consumer products like cars or over-the-counter medication bottles. Rather, the firearms industry self-polices its products, establishing its own design standards and initiating its own voluntary recalls.

In the absence of federal safety guidelines for the gun industry, some states like California have stepped in to regulate firearms sold within their borders. But gunmakers have not rushed to meet such standards to gain access to those states’ retail markets. Sales in states without any safety regulations more than make up for lost revenue in places like California, says Stephen Teret, a professor at Johns Hopkins who has studied the prevalence of gun safety features. “The gun makers have an enviable position: they’re selling a lot of guns without having to seriously invest in R&D,” says Teret. “It’s as if Ford was still selling the Model T.”

Chambered round indicators

This feature is located on the top or side of the slide to inform the user of a semiautomatic pistol whether a round is in position to be fired. Indicators — such as a piece of metal that pops up when a round is ready — are cheap and simple for manufacturers to install, but a 1999 study in the Journal of Public Health found that only 11 percent of pistol models released during the previous year included such a mechanism.

Some gun activists are skeptical of the devices, claiming they would be redundant if people followed the first of the “four rules of gun safety” — always treat a gun as though it’s loaded. But firearms owners and users do not always heed that advice.

California requires that all new guns sold in the state be equipped with chambered round indicators. That mandate is now being challenged in federal court by two gun groups, the Second Amendment Foundation and the Calguns Foundation. They argue that the requirement is unconstitutional because the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in its 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller decision that the Second Amendment gives individuals a right to own guns “in common use” — and many handguns commercially available outside California don’t incorporate chambered round indicators and other features at the heart of the suit.

Even as some gun rights advocates bristle at the California standards, it’s clear that these chambered round indicators address a real public health need. A 1991 study by the Government Accountability Office showed that over two years, nearly a quarter of accidental firearms deaths occurred when people mistakenly thought their guns were unloaded.

Magazine release safeties

Semiautomatic handguns, the most popular type of weapon in the U.S., are loaded with ammunition held in a detachable magazine, which feed a round into the chamber after each shot. Typically, if a round is cycled into the chamber, it remains in place ready to be fired even after the magazine has been removed, meaning the gun is still lethal. Magazine-disconnect features block the gun from firing when the magazine has been taken out.

Some firearm manufacturers, like Smith & Wesson, have long incorporated magazine disconnects into almost every model they make, but the 1999 Journal of Public Health study found that only 14 percent of pistol models overall used a magazine release safety.

Heavier trigger pulls

One way to prevent some accidental shootings is to make discharging firearms slightly more difficult. Guns with “light” pulls are more likely to fire when dropped, or when they snag on a piece of clothing. The best known Glock pistol, the 9mm Glock 17, requires only a relatively dainty 5.5 pounds of pressure on the trigger in order to fire.

But officers in the New York Police Department use modified Glocks with increased trigger pull weight. Glock makes two “New York” trigger attachments — a piece of plastic with a spring — that increase the amount of force required up to 11 pounds, reducing the chances of an unintentional shooting or a premature discharge during a tense moment. Some gun advocates, however, raise doubts about heavier trigger pulls, believing that they make guns less accurate — and thus more dangerous — because the shooter has to exert nearly twice as much force to fire the weapon.

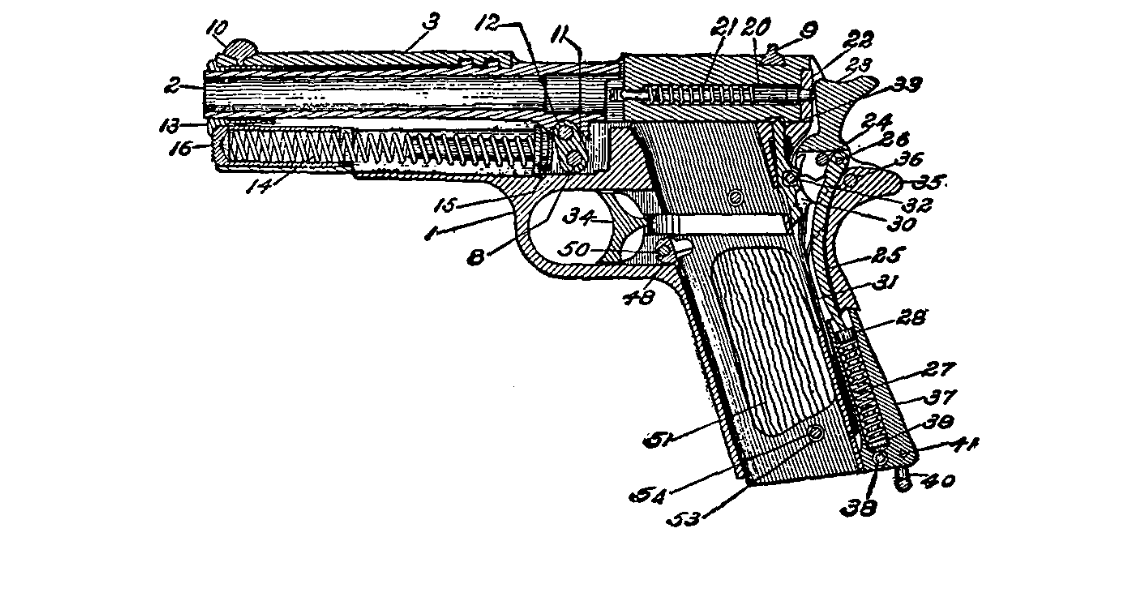

Grip safeties

Most handguns have a manual safety — a switch, button, or lever that must be disengaged to allow the gun to fire, even when a round is chambered. But some models also have a grip safety: a lever on the rear of the gun that must be squeezed with the flesh just below the shooter’s thumb to allow the gun to fire. The feature is found in many 1911-style semiautomatic pistols, and the popular manufacturer Springfield Armory includes them in its XD series of handguns.

John Hopkins’s Stephen Teret, one of the authors of the 1999 Journal of Public Health study, says he likes grip safeties because they are particularly suited to reducing the risk of accidental shootings by children. A 1995 study found that 25 percent of 3- and 4-year-olds, and 90 percent of 7- and 8-year olds, can fire a gun even with a heavy 10-pound trigger pull weight. But even if children that young can pull a trigger, they have a harder time getting their hand firmly around a pistol grip to squeeze the grip safety.

Firing pin blocks

Before a handgun model can be sold by a retailer in California, it first has to pass a test to see if it discharges when dropped. The federal government also imposes a drop-test standard on imported handguns: They were included in the 1968 Gun Control Act, a provision aimed at halting the flow of cheaply made European pistols favored by criminals of that era. Some handguns pass drop tests simply because they’re well constructed, while other revolvers and semiautomatic pistols incorporate features specifically designed to prevent the weapon from firing when dropped. Firing pin blocks — which are found in the 1911-style pistols made by Colt and Kimber — prevent a gun’s hammer from striking the pin unless the trigger is pulled to move the block out of the way.

[Photo: Public domain]