On November 5, 2014, Leann Schuldies went to a district court in Twin Falls, Idaho, and applied for a temporary restraining order against her live-in boyfriend. She had been trying to separate from 36-year-old George Salinas Jr., the father of her four youngest children, who kept threatening to kill her.

Ten days later, Salinas fatally shot Schuldies and her 17-year-old daughter before killing himself with his shotgun. A hearing to secure a final protective order had been scheduled for November 26.

Federal law prohibits someone from possessing guns if they are under a final protective order for domestic abuse or have been convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence. But it doesn’t specify how to take away the guns already in the possession of alleged abusers, and for practical purposes, the job of removing firearms falls to local law enforcement. Left to craft their own frameworks, states have produced a patchwork of statutes for disarming violent partners.

Fourteen states — Idaho is one of them — have no statutes whatsoever governing gun surrenders, in domestic violence cases or otherwise. But even in states that have taken steps to protect abuse victims, laws often don’t go as far as they could to reduce the risks for people like Schuldies.

Experts believe that the period immediately after a temporary restraining order is sought can be especially dangerous, as the prospect of losing control of their victims can propel abusers to lash out. But 34 states do not compel someone served with a temporary restraining order to surrender their firearms, instead waiting for the outcome of a court hearing on a permanent order before a gun ban can be instituted and a gun (or guns) collected.

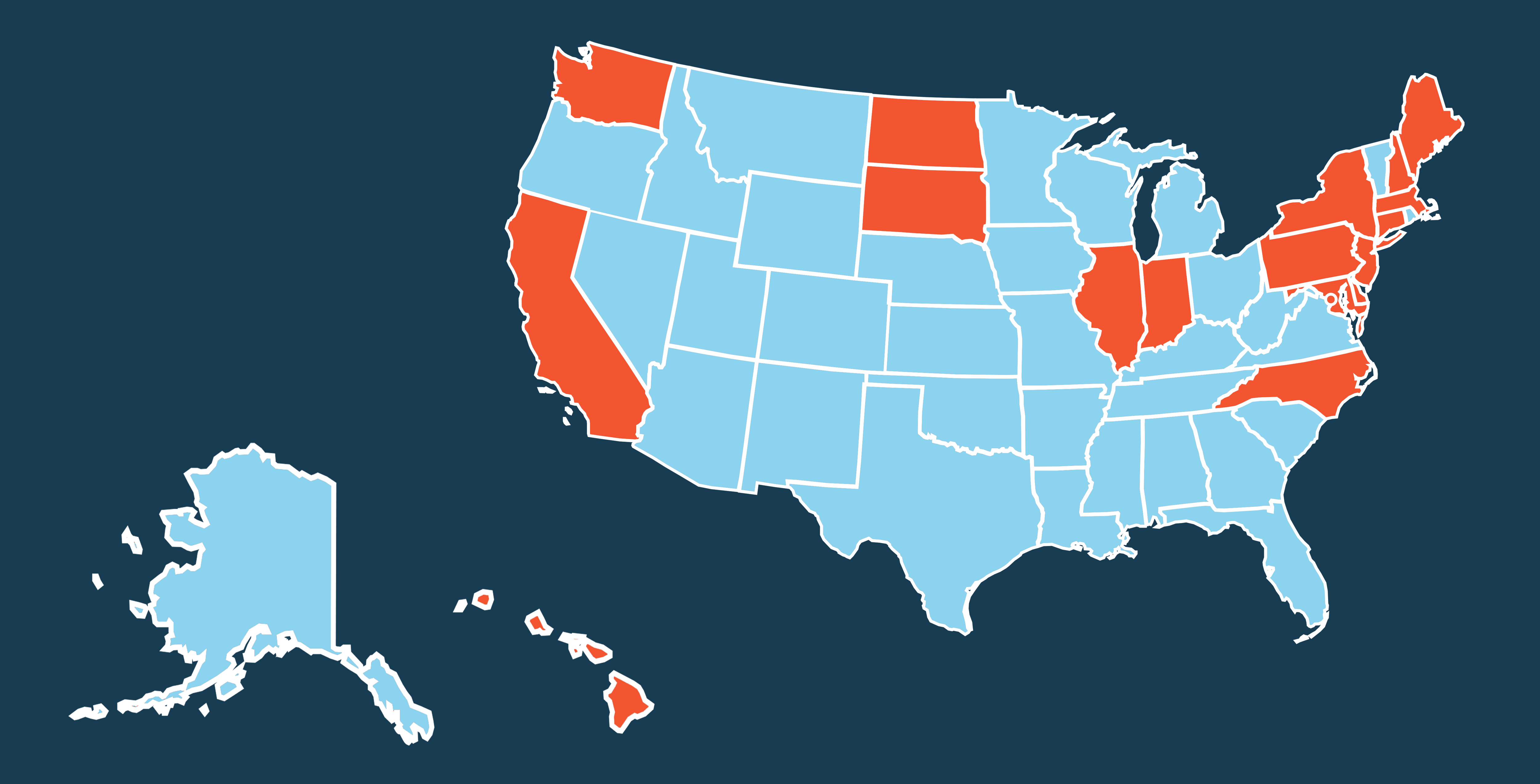

The exceptions — the sixteen states where just a temporary restraining order is enough to force an alleged abuser to relinquish his or her guns — are a motley group that includes both liberal California and the gun-loving Dakotas. Within this group is a kind of vanguard within a vanguard, where stipulations in the gun relinquishment law are meant to increase the odds that it is applied to every case.

In February, the Prosecutors Against Gun Violence and the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy jointly published a comprehensive review of state laws concerning domestic abuse and gun relinquishment, a slide from which is reproduced below. The report found that in a half-dozen states, courts are required to order someone who’s been served with a temporary restraining order to turn in his or her guns, while the remaining states give courts the discretion to decide whether to order the removal of an alleged abuser’s firearms. In none of these states is the process automatic — the person requesting the order has to check a box indicating that an alleged abuser possesses firearms in order to trigger removal.

Removing firearms when a restraining order is first served can save lives, says Karen Jarmoc, president of the Connecticut Coalition Against Domestic Violence and an advisor on a gun surrender bill that was signed into law Tuesday. When a domestic abuser receives a restraining order, Jarmoc tells The Trace, “it might be the first time their victim is taking back control,” and the sudden power shift can result in a lethal outburst.

In Connecticut, the law, which goes into effect October 1, requires alleged abusers to hand in their guns 24 hours after being served with a temporary restraining order. A bill which allows a judge to order the subject of a temporary restraining order to surrender his or her firearms was introduced in the Ohio House in March.

In its report, Prosecutors Against Gun Violence recommended that gun removals for persons under temporary restraining orders become a matter of federal law, “to ensure that victims are provided safety throughout the entire process” of escaping a violent relationship.