On summer evenings in 1999, a group of residents in the Chicago suburb of Skokie, Illinois, would gather on the corner of Foster Street and Hamlin Avenue, where a black man had recently been shot and killed by a 21-year-old white supremacist in front of his small children. In the muggy heat, they would stroll quietly past the neighborhood’s well-kept Colonial homes, driven by the need to remember what had been lost: a 43-year-old man, much beloved by the community, named Ricky Byrdsong.

Sixteen years later, at a press conference on Capitol Hill, the memory of that painful summer was evoked again. Last Wednesday, Sherialyn Byrdsong stepped up to the podium to tell her husband Ricky’s story to a roomful of reporters and gun reform activists. They had come together in the wake of the massacre at a historically black church in Charleston, South Carolina, to urge Congress to mandate background checks for all gun sales. Recalling her husband’s killer, she said, “That should sound familiar,” referring to racist Dylann Roof, the alleged Charleston gunman.

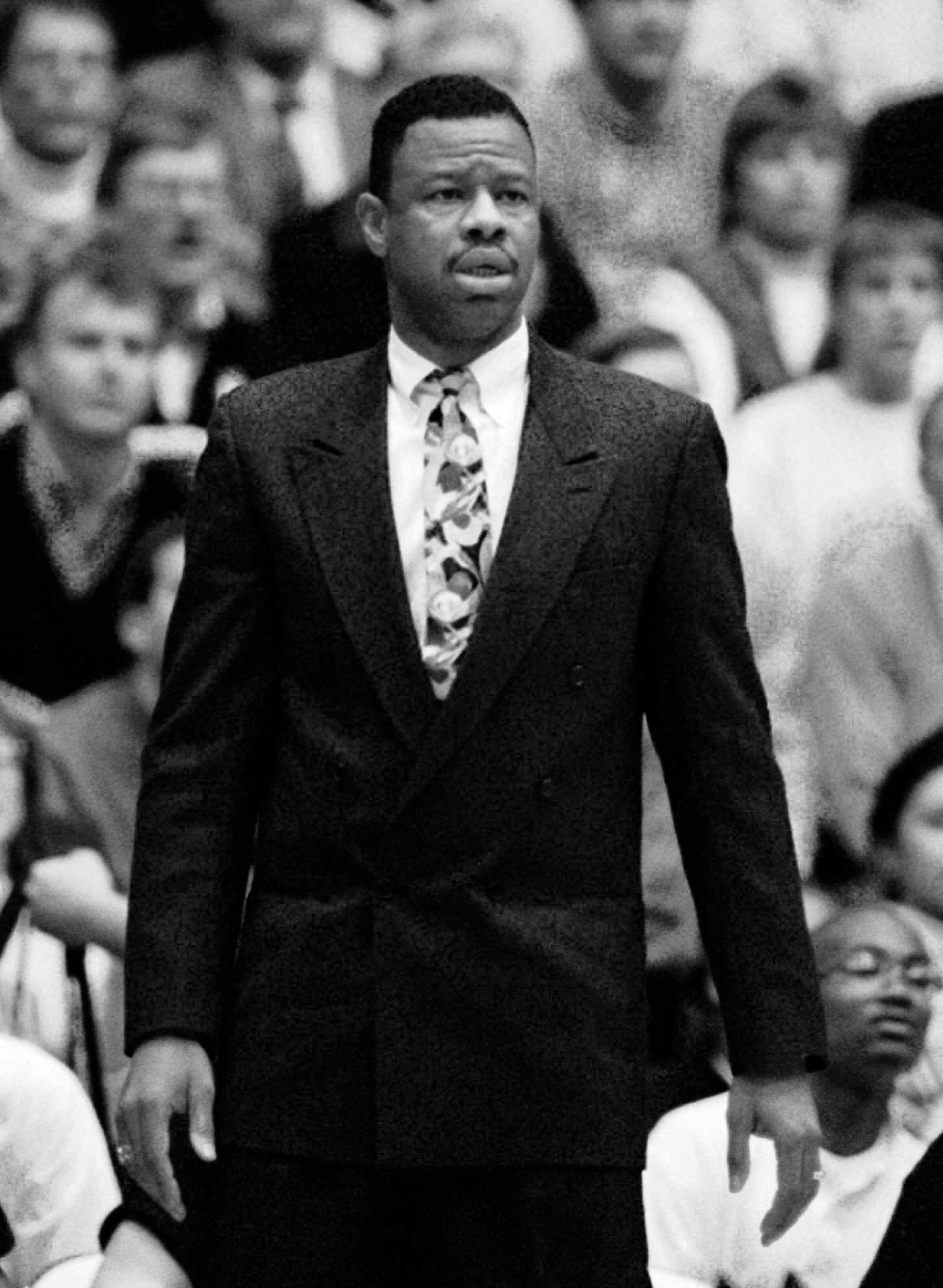

Byrdsong held up a framed family portrait in which everyone is dressed as if they had just returned from church. Sherialyn stands in the background, grinning proudly. Her broad-shouldered husband, Ricky, former head coach of Northwestern University’s basketball team, sits in front of her, surrounded by their three young children, the literal center of the family. He’d grown up without a father, in the projects of Atlanta, where whites would drive by and yell racial slurs at him and his younger sister. In the photograph, his smile is wide and warm — the expression of a proud man.

The Byrdsongs began dating when they were 16-year-olds, after meeting at a Christmas party. They went to college together at Iowa State University and got married after graduation. “We were living the American dream,” Sherialyn tells The Trace. “We had a house with the white picket fence,” and two girls and a boy to raise. Ricky coached college basketball, eventually taking the top job at Northwestern, a Big Ten school that competes against some of the best teams in the NCAA.

For four years his team floundered, forcing Ricky to resort to creative motivational tactics. Once, in an attempt to reverse what was about to become an eight-game losing streak, he abandoned the court and headed into the stands in a show of disgust. But the wins never really came, and in 1997 he was let go. Still, his players adored him. One of them said after his death, “I only wish I could have spoken to him to tell him I want to thank him for trying to make me a better person.”

In fact, Ricky was so well-liked at Northwestern that the head of the Board of Trustees hired him to work as a vice president at his insurance company. Through his new position, he started several programs for at-risk children. Sherialyn says, “He was a father figure to a lot of people, on a lot of different levels.”

Ricky was drawn to those who needed sympathy. He’d wander over to the children’s ward of the local hospital and perk up the kids, lowering his 6-foot-5 frame to meet their gaze. While working at the insurance company, he befriended a homeless man who panhandled across the street from his office. The trustee would later recount the story in a eulogy. “Ricky realized this was an intelligent man who was down on his luck and just needed a break,” he said. “After a couple of months, he came to me and said, I think this man can be an asset if you give him a job. Ricky got him dressed up, and I hired the man.”

Ricky liked to jog, and would often take his kids along. They would either bike or rollerblade beside him. On the night of July 2, 1999, he asked Sherialyn to take a walk. At the time, he was working on a book called Coaching Your Kids in the Game of Life, hoping, through the use of sports metaphors, to reach men who might not be inclined toward advice on how to be better to their children. Sherialyn said she had to run errands. So instead, Ricky took along their 10-year-old daughter and 8-year-old son.

Ricky was just a block from their house when Benjamin Nathaniel Smith, a neo-Nazi affiliated with the World Church of the Creator, shot him in the back. It was part of a random three-day shooting spree during which Smith fired at and wounded Orthodox Jews returning from temple; wounded an African-American minister in Decatur; and on the last day, July 4, murdered a 26-year-old Korean graduate student named Won Joon Yoon outside of a church in Bloomington, Indiana. He then crashed a car into a post during a high-speed chase with police, taking his own life.

Sherialyn remembers returning from her errands and her oldest daughter, age 12, frantically running down the street as she parked in the driveway. “Daddy’s been shot!” she screamed. When Sherialyn got to Ricky, he was still alive. “My husband was lying there, moving around in agony and pain,” she says. “His eyes were rolling around in his head.” A female police officer told her she thought Ricky would be fine. Four hours later he died from internal bleeding at a local hospital.

Some 1,600 people attended Ricky’s funeral at a church in Evanston. With the sanctuary at capacity, around a hundred Orthodox Jews sat outside on folding chairs to express their condolences. The Byrdsongs received calls from President Bill Clinton and Jesse Jackson.

Not long afterward, it came to light that Smith had first tried to purchase a handgun from a federally licensed dealer, but was denied when records showed that an ex-girlfriend had obtained a restraining order against him. He then turned to a man who sold firearms without a license, purchasing two handguns and exploiting a legal loophole in the background check system, which does not police private transfers.

By the time the news broke, the Byrdsongs’ neighbors had already begun their nightly walks around the neighborhood, the group growing throughout the summer, attracting people from towns miles away.

In the decade since, Sherialyn has been regularly asked to stand in front of a podium and call for laws that would make it harder for people driven by hate to get their hands on a gun. At Wednesday’s press conference, she made the pitch again. “I’ve been telling this story,” she says, “for 16 years.”

[Photo: AP/Fred Jewell]