In June, Rep. Chris Van Hollen, a Maryland Democrat running for Senate, introduced legislation that would put a surprisingly formidable obstacle between dangerous people and guns: a permit.

Yesterday evening, after President Obama made a statement about Thursday’s shooting at an Oregon community college, Van Hollen appeared on MSNBC, calling the day’s events “tragic” and “sickening.” He appealed to Congress to pass “common sense gun legislation,” including a permit to purchase requirement. Comparing gun ownership to driving a car, he said, “you should get a license before you can go purchase a weapon.”

To be clear, Van Hollen’s bill and a Senate version proposed by Connecticut Democrats Chris Murphy have little chance of becoming law while NRA-backed Republicans control both chambers of Congress. Nevertheless, the legislation contains what may be the most potent ideas for reducing gun violence that are currently under consideration at the federal level.

The bills, rolled out on June 11 with backing from Connecticut lawmakers Rep. Elizabeth Esty and Senator Richard Blumenthal, have strong data behind them, with numerous studies showing that such policies reliably reduce gun violence while stemming the flow of illegal firearms to criminals. There’s also evidence that even some gun-rights proponents might find something to like in them. What’s more, while Sens. Pat Toomey, a Pennsylvania Republican, and Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat, have only begun to consider reintroducing the background-check expansion bill that failed to pass after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook elementary school, these bills have already been filed.

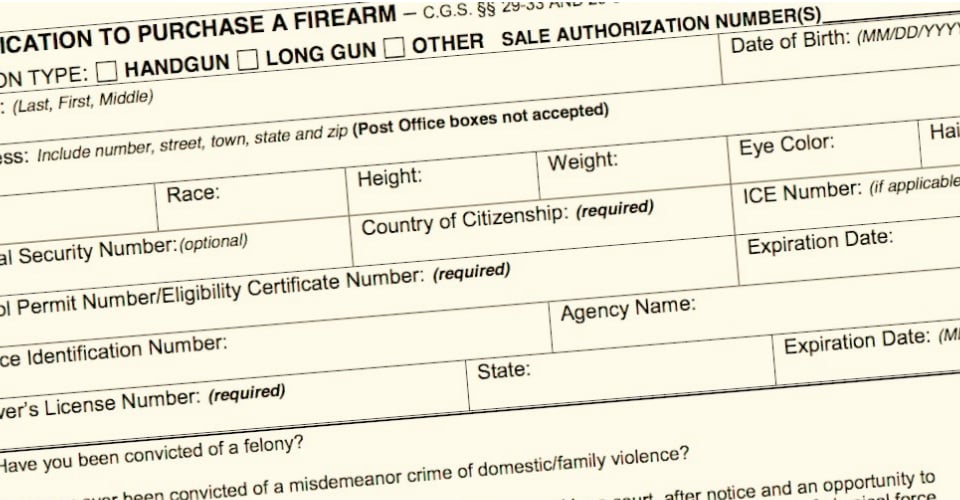

Van Hollen’s bill, which we’ll focus on in this piece, would facilitate what’s known as a national permit-to-purchase (PTP) requirement for all handguns, including those sold at gun shows and through private parties. To buy a handgun, a person would need to first possess a permit, which itself would be contingent on satisfying a number of requirements, the most significant of which is the passage of a background and criminal-record check. But the PTP system the legislation seeks to create goes further than the standard background-check procedure in place in most parts of the country: Prospective gun purchasers have to apply for their permit in person at a local law enforcement office, have their fingerprints taken, and submit a photograph along with their paperwork. Once a permit is granted, it’s good for five years. Holders who remain in good legal standing would not need to complete further background checks (as gun buyers do now) for additional gun purchases made during that period.

These standards would be set through a Justice Department grant program that would help states offset costs associated with the development of their individual permit-to-purchase systems. States would be free to go beyond the minimum requirements as they see fit.

In the past, some advocates of tougher gun laws have rallied around measures — such as assault-weapons bans — that hold more symbolic power than they do violence prevention benefits. Legislation like Van Hollen’s is built on a different criteria: What actually works? Nobody has thought harder about that question than public-health experts Daniel Webster and Garen Wintemute. After reviewing the scientific literature on firearm policy for a recent paper, the duo concluded: “The type of firearm policy most consistently associated with curtailing the diversion of guns to criminals and for which some evidence indicates protective effects against gun violence is PTP for handguns.”

How Permits Save Lives

Just 13 states currently have a PTP policy in place, and only three — Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York — have the kind of “discretionary” PTP laws most effective at saving lives and curbing gun trafficking. The key element of a discretionary PTP system is that local law enforcement has the authority to deny permits when a person who would pass a federal background check still poses a potential danger.

A team led by David Hemenway, Ph.D., at the Harvard School of Public Health recently conducted a survey of Massachusetts police chiefs in order to understand their reasons for rejecting permit applications under the state’s discretionary system. “Local police chiefs typically know more about the people in their community than does a national computer,” Hemenway wrote. The police chiefs interviewed in the study were particularly cautious when a permit-seeker had a history of assault, domestic abuse, mental illness, or substance abuse. Under the existing federal background check system, persons with a pattern of drug or alcohol addiction or a record of violent misdemeanors are typically cleared for gun purchases, despite those risk factors. A discretionary PTP system allows local law enforcement to consider such warning signs and withhold permits when justified.

“The goal isn’t to slow down the process for law abiding citizens. It’s to make sure that only law abiding citizens can purchase a handgun.”

One police chief interviewed for the study explained his justification for denying a permit to someone who would have otherwise passed a federal background check, describing the individual as someone with “no convictions, but was arrested numerous times for offenses including trafficking in cocaine, assault and battery, assault and battery on a police officer, resisting arrest, and destruction of property.” Another police chief used his discretion to forbid an applicant who had “made [a] statement that he was going to take his guns and go to one officer’s home and shoot him in the head.”

It was due to similar concerns that a law enforcement group in North Carolina came out against a measure that would have done away with the handgun-permit system in place there. Writing in opposition to the change, which ultimately was blocked, the North Carolina Sheriffs Association argued that, “[t]he sheriff has access to significantly more information about the applicant’s criminal record, pending criminal charges, mental health record, and other relevant data than is contained in the federal NICS system. To protect the citizens of North Carolina, all of the information required by federal law that is available to the sheriff should be considered when a decision is made about whether or not it is appropriate for a person to be authorized to purchase a handgun.”

Along with the hard-earned, frontline experience of law enforcement officials, there is strong empirical support creating a process for denying permits to high-risk persons who might slip past a federal background check. One study found that states with PTP laws allowing police discretion tallied a 76 percent reduction in the likelihood of guns winding up in criminals’ hands relative to comparable states without such laws.

Even without a discretionary policy, the best available research shows that PTP requirements in general are associated with lower rates of firearm-related mortality and reduced suicide rates.

Two studies published by Webster’s Center for Gun Policy at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health make this point clear. The first study found that, after the repeal of a 2007 Missouri permit-to-purchase law, statewide murder rates spiked 14 percent — which amounts to “an additional 49 to 68 murders per year.” This effect was significant even after controlling for changes in policing, incarceration, burglaries, unemployment, poverty, and other state laws adopted during the study period that could affect violent crime. The study also found that the repeal of Missouri’s law significantly increased the diversion of crime guns that were purchased in Missouri and later recovered by police in neighboring states, suggesting that Missouri’s PTP system had been making surrounding states safer as well.

The second Johns Hopkins study, released in June of this year, examined a 1995 Connecticut permit-to-purchase law similar to the one outlined in Van Hollen’s legislation. The researchers compared homicide rates in Connecticut 10 years after the law’s passage with the expected homicide rate in its absence. They discovered a 40 percent reduction in the state’s firearm-related homicide rate. Furthermore, the study found no substitution effect — that is, criminals in Connecticut did not switch to using other weapons to carry out homicide when they failed to obtain a firearm.

Going Beyond Background Checks

Not only do PTP policies have the potential to dramatically reduce gun violence, they also add powerful safeguards against guns landing in the wrong hands. Under existing federal law, the sellers in private firearms transactions are not required to ask buyers for identification. They are under no obligation to ensure that the guns aren’t being purchased for someone else. In all but three states, private sellers lack the capacity to even initiate background checks, should they want to conduct one. Often, there are no forms, no recordkeeping, and no oversight. This is why, in spite of federal law limiting the sale of handguns to persons under 21, an 18-year-old high school senior could walk into a gun show in most states right now and have a good chance of purchasing a handgun, no questions asked.

Unsurprisingly, private sales account for a massive number of the firearms used in crime — a survey of prison inmates on this question found that prohibited individuals purchased their firearm from a federally licensed retailer only 3.9 percent of the time. A PTP requirement would close this “private sales loophole” by requiring both licensed dealers and unlicensed vendors to sell firearms only to someone with a valid permit. Webster has preliminary research results indicating that private sellers may be eager to comply with that new mandate. In focus groups with gun owners about how they trade and sell their guns, some participants have mentioned only doing business with parties who can present a valid concealed-carry permit as proof that they’ve passed a background check. (A background check that, as discussed above, the private seller is usually not empowered to perform on their own.) This use of concealed-carry permits as validation that a purchaser is legal to possess firearms suggests that permits to purchase would build on ad hoc protocols that some private sellers have already created, without requiring major changes to their business practices.

Surveys have found significant support for the fingerprinting requirement, with 75 percent of poll respondents and 60 percent of gun owners in favor.

Another significant source of illegal guns is straw purchases, in which a person prohibited by law from owning a gun convinces a third party who can pass a background check to buy the firearm, then surreptitiously hand it over. According to a Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) study from 2000, straw purchases accounted for half of all trafficked guns in a given year. Sometimes, a willing accomplice is not even necessary to complete a fraudulent firearm purchase. In an investigation by the General Accounting Office (GAO), for example, investigators were able to purchase a gun without any resistance in five different states using a counterfeit driver’s license.

A national PTP system addresses these vulnerabilities by placing the burden of verifying a purchaser’s identity on law enforcement agencies, rather than private vendors. To secure a permit, the would-be straw buyer would have to first walk into a police station. The same would go for the convicted felon with his fake ID. Data indicates that a visit to the station or precinct house creates a strong disincentive to attempt fraudulent transactions. “Direct contact with law enforcement may deter straw purchases made on the behalf of a disqualified purchaser,” notes a policy brief from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Center for Gun Policy and Research, and “along with fingerprinting, ensures that the identity of the prospective purchaser is verified.” While putting law enforcement in charge of verifying IDs can scare away gun traffickers, legal purchasers, on the whole, don’t seem to mind the added step. Surveys have found significant support for the fingerprinting requirement, with 75 percent of poll respondents and 60 percent of gun owners in favor of needing to going through law enforcement prior to receiving a permit.

Why a National System Is Crucial

The importance of a nationwide permit-to-purchase system cannot be understated — in the absence of a universal policy, there is the risk that states with restrictive gun laws displace crime into states without.

In 2013, Maryland instituted a permit-to-purchase system as part of an ambitious gun violence prevention push. The law shares some of the elements of the national PTP system that Van Hollen’s bill would create, notably the requirement that most new gun purchasers submit fingerprints along with their applications, which are processed by the state police. When Baltimore suffered a surge of gun violence at the start of this summer, gun-rights advocates used this as proof that Maryland’s new gun laws aren’t working. But what those critics ignore is that the majority of Maryland’s crime guns are trafficked from outside the state — a byproduct of the fact that neither Pennsylvania, West Virginia, nor Virginia have permit-to-purchase systems of their own.

Permit-to-purchase is not a panacea (no policy is). The outcry over the death of Carol Bowne, a New Jersey woman killed by an ex-boyfriend while waiting for her handgun permit to come through, suggests that any effort to set up a national PTP system would surely face resistance. Steps would be necessary to ensure that applications would receive expedient responses, as Van Hollen seems to recognize. “Grant funding could make it possible to clear backlogs and speed up the application process,” says a spokesperson for the congressman. “The goal isn’t to slow down the process for law abiding citizens. It’s to make sure that only law abiding citizens can purchase a handgun.”

That’s a goal putatively shared by both sides in the gun debate, and one that a national PTP system has the potential to realize. There is perhaps no policy that has been more rigorously examined than permit-to-purchase, and the best available evidence consistently show its effectiveness. That was true when Webster and colleagues summarized their findings of a 2001 study of PTP policies, stating that they “ … have the potential to significantly restrict gun acquisition by high-risk individuals through stricter eligibility criteria, safeguards against falsified applications, and increased legal risks and costs associated with illegal gun transfers to proscribed individuals.” And it remains true today, when a focus on proven gun reforms is essential.