As the country reels from a pair of devastating mass shootings, the gun lobby has doubled down on the notion that “a good guy with a gun” is the only thing that can stop “a bad guy with a gun.” That maxim is central to the National Rifle Association’s decades-long mission to relax gun laws and increase gun sales. Right-leaning media outlets have amplified that message in recent years by reporting that instances of self-defense by law-abiding owners actually outnumber gun crimes.

But is it true?

A reader asks, Are there more instances of defensive gun use than gun crimes, and where does the claim come from?

The reality is that estimates of defensive gun use are so squishy that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in May removed all figures from its website. But below we do our best to separate fact from fiction.

What is defensive gun use?

It’s typically defined as using a firearm to protect yourself, your family, or other people from a crime. The gun could be fired or simply brandished. Examples include shooting an attacker in mid-assault or displaying a gun to discourage a burglar.

How many instances of defensive gun use are there each year?

The number of DGUs, as these incidents are commonly known, is hard to pin down. Law enforcement agencies don’t typically classify DGUs as a standalone category. The FBI tracks justifiable homicides, but states aren’t required to submit those figures, so the data is incomplete. And the FBI figures omit defensive assaults, in which someone fights off an attack, and brandishings.

This ambiguity has opened the door to a fierce debate between gun violence researchers and pro-gun advocates, who tend to cite different sets of data. Academics largely rely on the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), a twice-yearly poll of crime victims conducted by the federal government, while gun rights activists point to a series of telephone surveys conducted in the early 1990s by a criminologist and self-described “gun control skeptic” named Gary Kleck.

The NCVS identifies far fewer instances of defensive gun use. According to the most recent firearms violence report, published in April, 2 percent of victims of nonfatal violent crime — that includes rape, sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault — and 1 percent of property crime victims use guns in self-defense. According to the survey, firearms were used defensively in 166,900 nonfatal violent crimes between 2014 and 2018, which works out to an average of 33,380 per year. Over the same period, defensive gun use was reported in 183,300 property crimes, or an average of 36,660 per year.

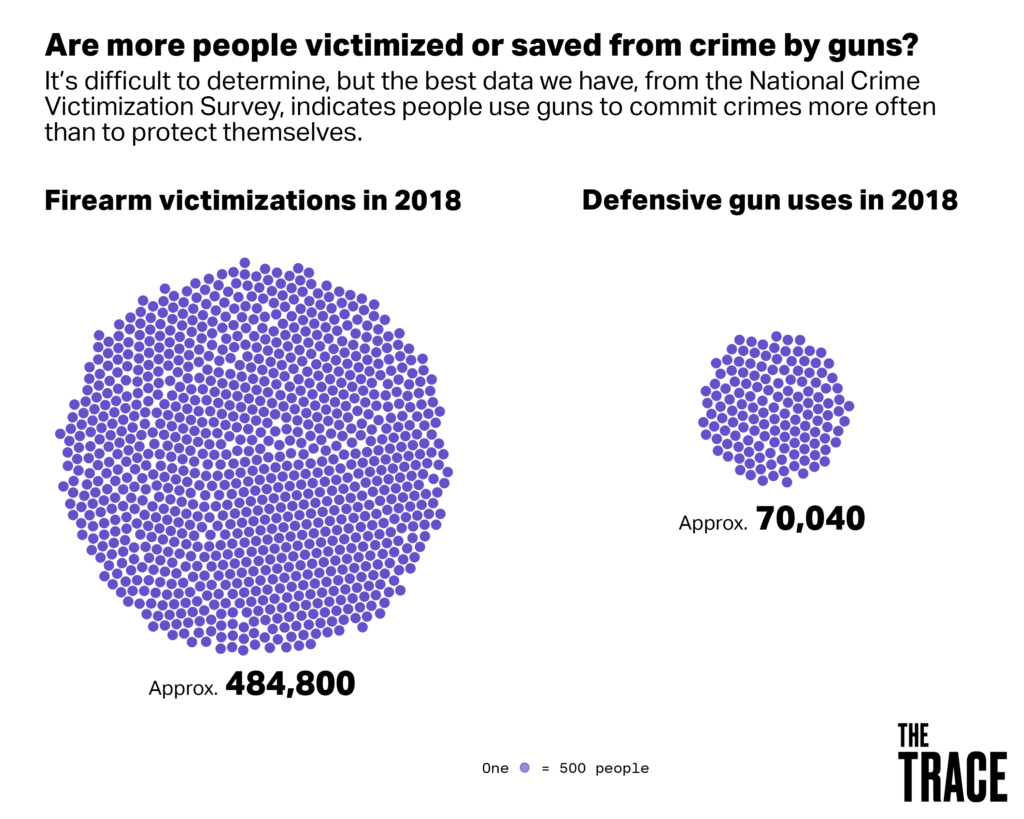

Taken together, that’s 70,040 instances of defensive gun use per year.

Notably, the NCVS figure excludes cases of simple assault. There are other caveats: Survey respondents are only asked about defensive measures if they report being victims of certain crimes, including rape, assault, burglary, larceny, and car theft. That means victims of trespassing and commercial crimes are not given the opportunity to report defensive gun use. And respondents aren’t asked directly about guns — they’re asked what they did to protect themselves or their property; it’s up to them to supply specifics.

More than 20 years ago, Kleck, who taught at Florida State University, reported a far higher figure, 2.5 million, and that’s been embraced by gun activists. In 1993, Kleck and his colleague Marc Gertz surveyed 5,000 adults and asked if they or their household members had used a gun for self-defense in the past five years, even if it wasn’t fired. Just over 1 percent of respondents said they did. In their National Self-Defense Survey, published in 1995, Kleck and Gertz extrapolated that figure to the entire adult population of 200 million, concluding that Americans use guns for self-defense as often as 2.1 to 2.5 million times a year.

Researchers have found several issues with Kleck’s estimates. While the adult population in the United States in 1993 was around 200 million people, not all of them owned guns — only about 42 percent did. So extrapolating the survey results to the entire adult population yields an overestimate. David Hemenway, director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, who first addressed “extreme overestimates” of DGUs 25 years ago, pointed out problems with Kleck’s math in 1997:

Guns were reportedly used by defenders for self-defense in approximately 845,000 burglaries. From sophisticated victimization surveys, however, we know that there were fewer than six million burglaries in the year of the survey and in only 22 percent of those cases was someone certainly at home (1.3 million burglaries). Since only 42 percent of U.S. households own firearms, and since the victims in two thirds of the occupied dwellings were asleep, the 2.5 million figure requires us to believe that burglary victims use their guns in self-defense more than 100 percent of the time.

Telephone surveys tend to yield high estimates for other reasons, Hemenway says. When it comes to quantifying rare events, even a small amount of misrepresentation on the part of the respondents can skew the results. People sometimes exaggerate when the action they’re describing, like fending off an attacker, is commendable or paints them in a heroic light, a phenomenon known as “social desirability bias.” That alone wouldn’t be enough to yield an overestimate, Hemenway said, but it does when measuring a rare event. “The search for a ‘needle in a haystack’ has major methodological dangers, especially where researchers try to extrapolate the findings to society as a whole,” he wrote in 1997.

Hemenway says that respondents might also “telescope,” or describe an event that’s outside the time frame that’s being asked about. And crime victims can also misremember traumatic events. Researchers consider the NCVS to be more reliable than randomized telephone surveys because respondents are asked screening questions that help weed out false reports, something that typically isn’t done with telephone polling.

Kleck, who is now retired, argues that respondents underreport DGUs because they fear the authorities. In some states, pointing a weapon at someone can lead to an arrest. Even if they’re eventually cleared, “you’ve lost thousands of dollars in legal fees, had your reputation ruined, maybe had your picture and name and the newspaper,” he said. The NCVS is confidential, but some gun owners may not trust that their answers won’t be passed on to the authorities, Kleck says. “They’re really unlikely to put themselves in legal peril by reporting that they wielded a deadly weapon, and pointed it at another human being. It’s a lot easier for people to report ‘I was a crime victim,’ period.”

Hemenway says that he’s never heard of a criminal case arising from the National Crime Victimization Survey. Ultimately, he says, most defensive gun uses happen during arguments, when tempers flare and guns are nearby.

Some researchers find fault with both the low- and the high-end estimates. The RAND Corporation found the 2.5 million DGUs per year was “not plausible,” given more “trustworthy” sources like the NCVS. But RAND also said the government’s DGU figures are likely an underestimate. “The fundamental issues of how to define DGU and what method for obtaining and assessing those measurements is the most unbiased have not been resolved,” RAND researchers wrote, and encouraged further research.

Are there any real-time stats for defensive gun use?

Yes, but there are caveats.

Gun Violence Archive, the Kentucky-based nonprofit that tallies gun-related incidents in near-real time, also counts DGUs. But it only captures incidents that make the news or are reported to police. And GVA includes incidents involving illegal gun possessors as well as legal owners, including shootouts as well as stand-your-ground shootings. GVA recorded 8,394 DGUs from 2017 to 2021, which works out to an average of 1,678 a year. But that’s likely a massive undercount.

The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, launched a DGU tracker in 2019 that relies on media reports, but counts only defensive gun use by lawful owners. Heritage tallied 2,106 shootings from 2019 to 2021, for an average of 702 per year. The group cautions that it’s “not intended to be comprehensive” because “most defensive gun uses are never reported to law enforcement, much less picked up by local or national media outlets.” That’s a common belief among pro-gun advocates, some of whom believe the 2.5 million figure is, in fact, too low.

There’s no way of proving if DGUs are underreported to police. But according to the National Crime Victimization Survey, nearly 70 percent of nonfatal firearm violence is reported to the authorities.

How many gun crimes are there each year?

The NCVS’s most recent firearm violence report tallied 14,000 gun homicides and 470,800 incidents of nonfatal firearm violence — which includes armed sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault — among people 12 and older in 2018. That adds up to 484,800 gun crimes.

Are there more instances of defensive gun use than gun crimes?

No. If we’re going by NCVS data, DGUs do not outnumber gun crimes. There are seven times as many gun crimes (484,800) as there are instances of defensive gun use (70,040) each year, according to the survey.

Leading researchers back that up. The Harvard Injury Control Center has found that guns are used far more often to intimidate others than in self-defense.

If most academics go by the crime victim survey data, why do the higher DGU estimates persist?

Because they’ve been repeatedly amplified by the gun lobby, mainstream media outlets, and even the the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For years, the CDC cited DGU estimates from both the NCVS and Kleck’s surveys, saying that estimates range from “60,000 to 2.5 million defensive gun uses each year,” and linking to a 2013 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine that cites Kleck.

But that changed last month, when the CDC removed those figures and replaced them with more general language:

Estimates of defensive gun use vary depending on the questions asked, populations studied, timeframe, and other factors related to study design. Given the wide variability in estimates, additional research is necessary to understand defensive gun use prevalence, frequency, circumstances, and outcomes.

The edits followed months of lobbying by a group of researchers that included Mark Bryant, who leads Gun Violence Archive, and Devin Hughes, who runs GVPedia, a nonprofit gun violence research outfit (Hughes is a former Trace contributor). Mainstream media outlets have also begun re-evaluating the 2.5 million figure. But the belief among Americans that guns are a tool for self-defense is a persistent one, regardless of what the data says. And it remains the centerpiece of the NRA’s strategy, according to internal documents recently unearthed by my colleague Will Van Sant.

“We know from repeated research that the vast majority of Americans agree that law-abiding people have the right to defend themselves and their families with the firearm of their choosing,” the NRA’s research director wrote in a January 2021 memo to board members. “This is why no matter the policy, our messaging continues to focus on self-defense.”

Defensive gun use, Hemenway said, “is the linchpin of almost all the arguments about having a gun.”

Another reason DGU overestimates are repeated across decades is because most studies on the topic are more than 20 years old. In interviews, both Kleck and Hemenway say they consider the science to be settled. Kleck hasn’t repeated his telephone survey in nearly 30 years, while Hemenway points to the NCVS as a current barometer of defensive gun use. But both men concede that the true number of DGUs will probably never be known.

“What we do know for sure,” Hemenway said, “is that having a gun in your house increases suicides, it increases gun accidents, and it increases homicides, at least of women in the house. And we can’t find any benefit from it.”