On April 8, President Joe Biden topped off a series of executive actions on guns by tapping David Chipman to lead the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. Chipman, a former ATF special agent turned gun violence prevention advocate, would be the bureau’s first permanent, full-time director since 2015, and his nomination reflects the White House’s determination to strengthen federal gun regulations.

Chipman served for 22 years as a special agent for the ATF, where he led the bureau’s firearms enforcement programs, combated firearms trafficking, and helped coordinate national violent crime strategy. Since retiring from the ATF in 2010, he’s advised the gun reform groups Everytown for Gun Safety and Giffords, where he has held the position of senior policy advisor since 2016. He has also worked as an executive at ShotSpotter, a purveyor of gunshot detection systems. (Everytown provides grants to The Trace through its nonpolitical arm. Here’s our list of major donors and our policy on editorial independence.)

Chipman’s Senate confirmation is far from assured. He will need the votes of every Democrat and at least one Republican to assume the post. His advocacy work will likely engender stiff opposition from Senate Republicans and gun rights groups. The National Rifle Association tweeted shortly after the announcement that his position at Giffords presents “a clear conflict of interest” for Arizona Senator Mark Kelly, who co-founded the group, and must vote on Chipman’s nomination.

But supporters say that as a reform advocate and a gun owner, Chipman will be able to strike the right balance between gun rights and public safety. During a 2019 House Judiciary Committee hearing on assault weapons, Chipman testified that there was “absolutely nothing controversial about acknowledging that some people simply shouldn’t have guns.”

“We should not tip the scales on the side of convenience, but on the right to live in a country absent the fear of getting shot and killed in the line of duty, or at a movie theater or in your daily affairs,” Chipman added.

Chipman has advocated for some of the same measures that Biden announced he is implementing via executive action, including stiffer regulations on ghost guns and firearm accessories. Chipman has also expressed support for the nationwide adoption of red flag laws, which provide a mechanism for temporarily disarming people who may pose a danger to themselves or others. Chipman, who spent part of his career working to combat gunrunning along the East Coast’s I-95 corridor, will also be able to lend his expertise as the Department of Justice works to produce its first report on firearms trafficking in two decades.

Chipman has spoken to The Trace several times since our launch in 2015. Here are excerpts from our archives that illuminate his positions on firearms policy and provide a glimpse of what his priorities might be if he’s confirmed.

He wants to regulate semi-automatic rifles — not ban them

After the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, galvanized support for a new ban on assault-style weapons, Chipman said such a measure would be nearly impossible to enforce given how millions of those guns were already in circulation. Chipman told The Trace:

“We have to deal with all the guns that are already out there. There are already millions, and law enforcement just doesn’t have the capacity to kick all those doors to take them.”

In 2018, Giffords proposed a different tact: regulating assault-style weapons under the National Firearms Act, the 1934 federal law that restricts machine guns, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, and silencers. If AR-15s and similar weapons were brought under the NFA, owners would be required to register them with the ATF and pay a $200 tax.

He supports regulating more gun accessories under the NFA

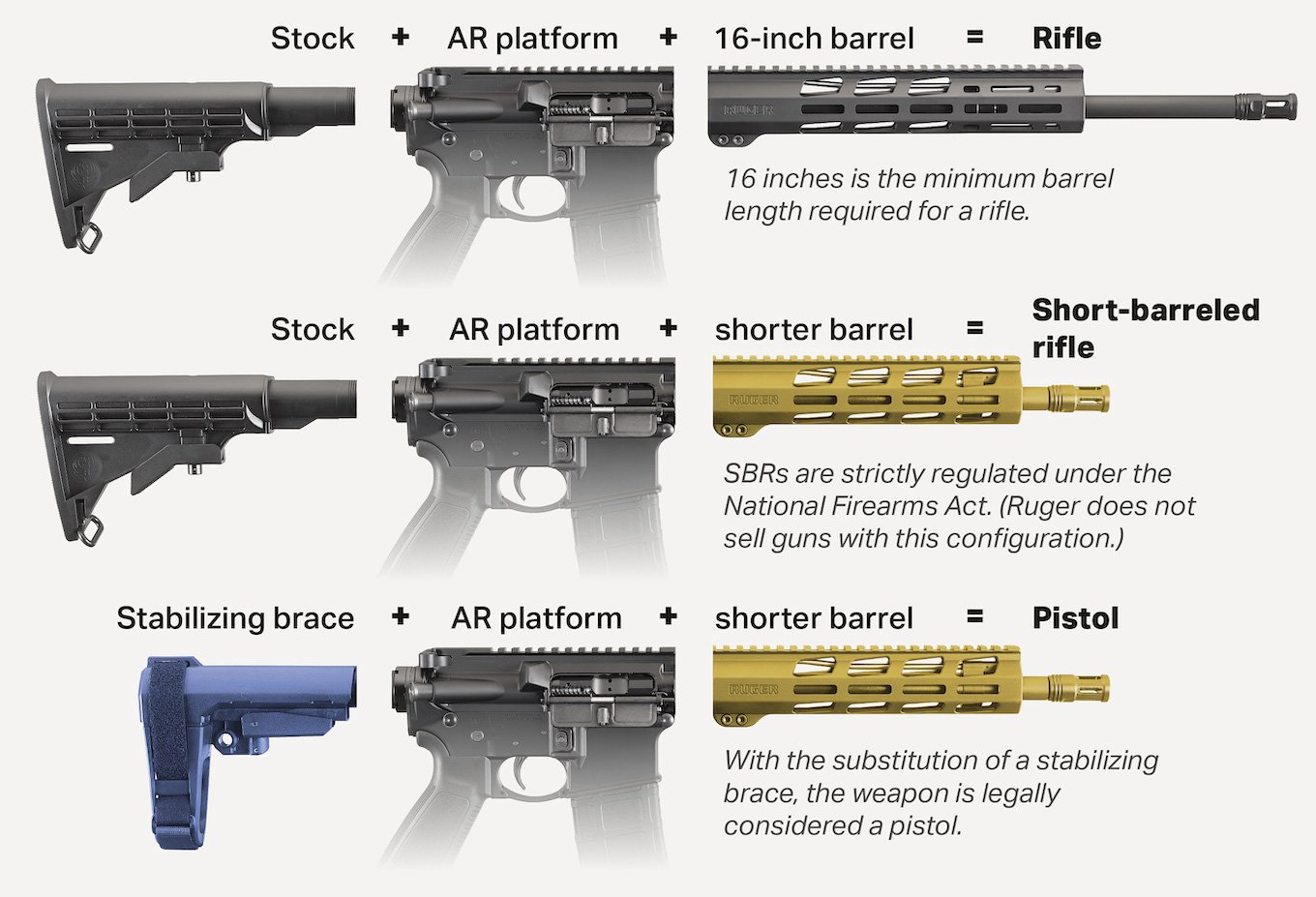

One of President Biden’s executive actions directs the Department of Justice to issue a rule regulating AR-style pistols equipped with stabilizing braces under the NFA. Chipman has criticized the ATF’s inconsistent approach to stabilizing braces since the devices came on the market nearly a decade ago. In 2018, Chipman wrote that the bureau had failed to address “the significant public safety threat” posed by stabilizing braces and advocated bringing the devices under NFA controls.

Chipman has also warned about the hazards of removing silencers from NFA regulation. In 2017, he testified before a House subcommittee against a Republican-backed bill to deregulate silencers, also known as suppressors. The hearing came three months after the Congressional baseball shooting, which wounded U.S. Representative Steve Scalise and three other people. During his testimony, Chipman argued that the sounds of unmuffled gunfire served a public safety purpose:

“Lives were spared that day because people recognized the unique sound of gunfire and were able to take cover. Now, Congress is promoting a bill that would make a situation like the one experienced in Alexandria potentially even more dangerous by putting silencers in the hands of criminals, and making it more difficult for people – including law enforcement officers – to identify the sound of gunshots and locate the active shooter.”

The bill ultimately stalled.

He has opposed increased federal prosecutions for gun crime

During his confirmation hearing for U.S. attorney general in 2017, then-Senator Jeff Sessions touted federal gun prosecutions as an effective crime-fighting measure. But the Justice Department’s own research has found that the stiffer sentences meted out in federal court don’t do much to deter crime. Chipman echoed that assertion, telling The Trace that, if such a strategy were employed on a nationwide scale, it would reverse a trend toward de-incarceration that’s been embraced by criminal justice reformers in recent years: “Just throwing a lot of people in jail is sort of moving back policing to an era that I thought we had moved past.”

He has spoken out about NRA-backed limitations on crime gun tracing

The ATF is forbidden by law from creating a centralized computerized database of gun dealers’ inventories. So when the ATF needs to trace a crime gun, it has to rely on records maintained by individual stores. Most of these records are kept in handwritten books because, until five years ago, gun dealers were barred from maintaining electronic inventories without special ATF approval. After Hurricane Harvey threatened to wipe out gun dealers’ inventories in Texas and Louisiana in 2017, Chipman told us that the NRA-backed ban on a centralized government database had constrained the bureau’s ability to get shooters off the street:

“You lose the ability to connect the dots in an important investigation. This is one of the real potentially catastrophic downsides of the gun lobby efforts to block the ATF from modernizing traditional recordkeeping requirements.”

Chipman knew from experience: When he was an ATF agent in 2005, Chipman had to sort through troves of gun store records damaged by Hurricane Katrina. Chipman said the waterlogged records were “one of the most troubling things we had to deal with.”

He has revealed the struggles of the underfunded, undermined agency he’s now been chosen to lead

In 2019, after an ATF contractor stole thousands of guns and gun components that had been seized from criminals and were slated to be destroyed, Chipman told The Trace that the bureau’s gun destruction process was riddled with security gaps.

Before the early 2010s, Chipman and his fellow ATF agents were required to dispose of recovered guns themselves, and they had to find a local facility willing to destroy them. Sometimes they took weapons to carmakers, like Ford in Detroit, and melted them in their smelters. Other times they used recycling facilities, where specialized hydraulic metal-cutting machines sheared through the guns’ frames. Because these businesses provided gun-destruction services out of goodwill, they were not always timely. That led to a backlog in confiscated crime guns, forcing field offices to store large numbers of guns for months at a time — and creating an opportunity for theft.